Sacrificing the Self

April 4, 2025

Excerpt: Bias is just you using your expectations and assumptions to ignore the noise, and see the picture more clearly. The trade-off is that, sometimes, the noise is useful or your expectations are off. Mob-mentality and groupthink are usually posed as scary features of groups. But they’re just another example of this trade-off, and usually they’re more good than bad.

When we want to identify with a group, we bias ourselves to filter out all theother ways we could be. It helps us cut down all our competing priorities to the group. The trade-off is the benefit in diversity of thought.

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

In the first part of this series, I tried to convince you that bias was a good thing, then I promised that I’d show you how that plays out in human behaviour. So let me recap the main idea to save you reading that first article again, and then I’ll get into showing you how. In this article it’ll be by showing you how our desire to be a part of groups promotes team performance through bias.

Find the rest of the series collected here.

If you already read the first part, then you can skip to the showing

Recap

Behavioural economists have the world terrified of biases. Groupthink, confirmation bias, negativity bias, optimism bias, etc, etc. You’ve probably read about at least one of them. You see, behavioural economists:

work off the assumption that humans are ‘rational actors’. They call it the ‘rational-actor model’. The idea, more-or-less, is that if you give a human a decision to make, they will decide by optimising for their preferences, weighing up the costs and benefits. You do stuff that does the most good for you, and the least bad. On this model, errors should only happen when you don’t have the right information to make the ‘rational’ decision. … ‘biases’ … are times when we deviate from this model. When we make choices that are not optimised to our preferences, maximising benefit and minimising cost, despite having accurate information.

But statisticians don’t see bias this way, and the brain is much closer to a statistician than an economist. For them, bias is one half of a trade-off.

Bias is the opposite of noise, or variance. If you have a biased measure, it’s more precise. A noisy measure is more variable. But that’s orthogonal to accuracy—both biased and noisy measurements can be either accurate or inaccurate.

The idea is that, sometimes, you want to use your expectations and assumptions to ignore the noise, and see the picture more clearly. The trade-off is that, sometimes, the noise is useful or your expectations are off.

This is, more-or-less, what the brain does:

the brain, and nervous system more broadly, has to map all the noise out there in the world to produce the right response. Not only that, but it has to coordinate all the noise inside your body to do it. Nerves innervating, muscles activating, hormones sloshing around in glands.

And most of the time, this is predictable … the brain maps the predictable structure of the world and your actions within it. By paying attention to the predictable stuff, and biasing your actions as a response, it can ignore all the irrelevant noise that might lead you to make an error. This frees it up to do more complicated processing when it doesn’t know what to expect—when it needs to pay more attention to the noise.

So, that’s the first article. Let’s look at an example.

(Some of) Group formation is about bias vs noise

I should admit that I wrote an entire other series that circled around some of what I’m going to write about today. But I want to zoom in on just one aspect in this article.

That series was a pointed attack on the classic narrative that people will:

cheerfully engage in the most obscene behaviour if either:

- Everyone else is; and/or

- Someone charismatic/in authority tells them to.

You’ve almost certainly heard of ‘mob-mentality’ or ‘herd-mentality’ or ‘us-vs-them’ or ‘groupthink’. We love to create narratives around how dangerous group dynamics are. And that series talks about how, actually, catastrophic group dynamics are actually really hard to achieve.

But the element of the series I want to zoom in on is the bit that talks about how, actually, we really want group biases because biased groups make for the best kinds of groups.

First, what attracts us to groups

Social Identity Approaches are a cluster of theories that explore one of the main things that attracts us to groups. They ask the question “what’s the difference between groups we’re attracted to, and other similar groups?”

So, why do we choose one job over others, or a crossfit gym over other exercise groups, or one social circle over all the others we encounter?

The answer isn’t going to surprise you. Social Identity Approaches say that there are probably heaps of reasons, but a big chunk of them are all the ways a group reflects who we think we are and who we want to be.

You might join one job over others because it’s more fun. But part of that is because you think you’re a fun kind of person. You might join a crossfit gym because it’s more about functional fitness than other gyms,1 but part of that is because you see yourself as a practical person. You might choose one social circle over others because the conversation is more interesting, but part of that is because you think you’re a bit of an intellectual person.

You get the idea. But there’s an important addendum here. All these ways the group reflects who you are and who you want to be are completely irrelevant without the comparison to other, similar groups.

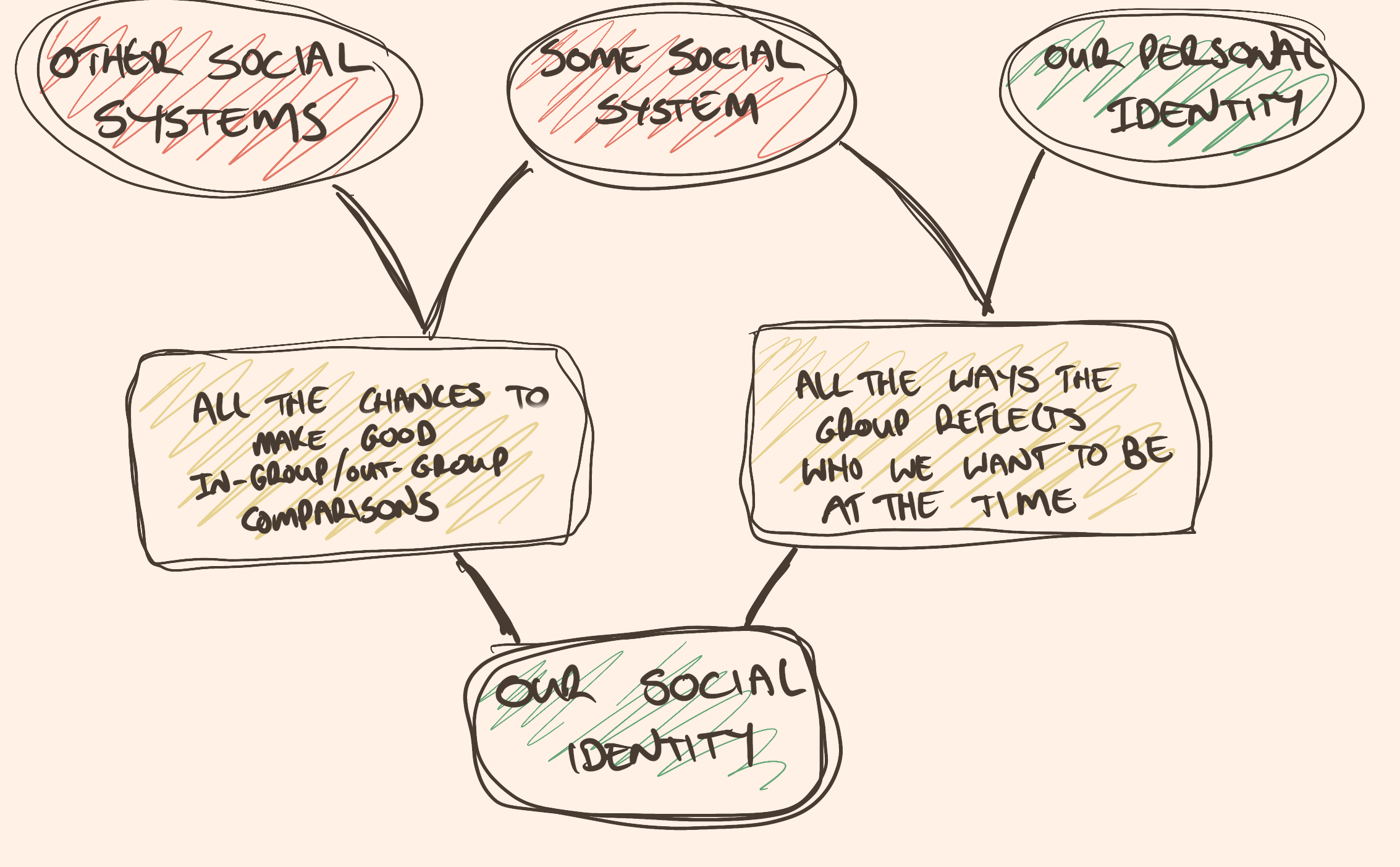

A little sketch of the main things involved in the

creation of our social identity. All ways we the group reflects who are and

want to be at a given time, combined with all the chances we get to make

in-group/out-group comparisons that favour our group make up the strength

of how closely we identify with that group. The important thing is the

comparisons, otherwise all the ways the group seems to reflect us will seem

irrelevant.

A little sketch of the main things involved in the

creation of our social identity. All ways we the group reflects who are and

want to be at a given time, combined with all the chances we get to make

in-group/out-group comparisons that favour our group make up the strength

of how closely we identify with that group. The important thing is the

comparisons, otherwise all the ways the group seems to reflect us will seem

irrelevant.

Like, in the UK I like to play up my Australian-ness because we have better beaches, better weather, and better coffee than the people in the UK, and I reckon I’m a beachy, sunny, coffee-drinking kind of person. But it doesn’t make any sense to go to Australia and play up my Australian-ness, because everyone’s Australian there.2 Instead, I play up that I’m from Sydney, because we have better beaches, better weather, and better coffee than our soggier friends from Melbourne.

Similarly, you might be a crossfitter when you’re comparing yourself to other gym-goers, but you’re just a healthy, sporty person when you’re comparing yourself to people who don’t have an exercise addiction. People who don’t go to the gym probably don’t know or don’t care about whatever crossfit is supposed to be, so the more specific identification is irrelevant.

Second, why attraction makes us biased

If we become aware of these kinds of positive distinctions—group traits that reflect who we are and who we want to be relative to some other group we’re aware of—we’re going to start accentuating these things.

I want to distinguish myself from the British people around me, so I start accentuating my Australian accent and using our funny slang more. Now everyone is clear that I’m different, and they’re making the kinds of assumptions about me that I want them to make. You might want to distinguish yourself from people who are less health-oriented, so you start wearing athletic clothes and talking about your run times or whatever. Now, people are going to see you in a light that reflects the kinds of things you really care about.

But, to get back to my point about bias vs noise, it’s not quite so superficial as all this. There’s a lot going on here at a deeper level. So, part of it is about signalling to out-groups what kind of person we are, as I’ve described above. Part of it is on the other side of that equation. You also want to fit in and be accepted by the group you care about—so-called ‘normative conformity’. There’s also an informative influence here—when you don’t know how you’re supposed to be behaving and you’re trying to improve yourself or simply not make a fool of yourself, you’re going to adopt group norms more strongly.3

But some of it, the part we care about for this article, is about reducing noise. You see, our individual identity is a thousand buzzing fragments, all in a constant pull-and-push with each other. You are a noisy creature, full of conflicting and overlapping desires and ways of being. And this isn’t really all that functional.

Take this hypothetical crossfitter we’ve been using as our example. Crossfit is an example I use to illustrate mundane cults—it’s a values-based business, in the sense that people are paying for a way of being more than they’re paying for the product the company sells. You can throw medicine balls around and jump on boxes just fine by yourself. You’re don’t need to pay for access to these things—it’d be cheaper to buy them and watch a couple videos online. What you’d be paying for is the access to a community which feels the same way about exercise as you do. Who care about health like you do. Who want to live a life that’s similar to the kind of life you want to live. So you justify the expense.

But then you leave, and without thinking, you go and grab an expensive latte loaded with sugary syrup, and a slice of mud cake. And you’ll rationalise this to yourself. Maybe you’ll say that you earned it. Or that you’re normally healthy. Whatever. The reality is that you’re a noisy human, and you’re not particularly coherent all the time. There are lots of different bits of you competing for your time and attention and access to your decision-making. And one of the things your mind will do is smooth over these things so you don’t come apart at the seams. This tension and the need to resolve it is called cognitive dissonance.45

When it comes to groups, this process of resolving dissonance plays out in a very interesting way. See, when you factor in groups, you don’t just have little pieces of yourself competing with each other, you also have your different group identities competing with each other. Like, you probably can’t bring the kind of corporate jargon you speak at the office to the gym, because no one will know what the fuck you’re talking about.6 Crossfit might be a disruptive way to train, but that’s not a phrase that’s going to get over the net at your post-exercise coffee. You’ve got to code switch—pick up a completely different in-language. Probably, there are a bunch of other things you need to switch too—behaviours, clothes, norms.

In a group setting, this capacity for switching is a real problem. All these things exist inside you. You can occupy any of them, or none. You could be the weirdest version of yourself—the one that talks to themselves when they’re at home alone (just me?). You could be the corporate version. The networking version. The party version. And in each of these settings you have individual parts you competing for expression, alongside the pressure to be like whatever groups you want to be like.

But, when you’re trying to emphasise your relationship to one group, you don’t want to be all this messy stuff. You want to be part of one group. So you’re going to start to bias yourself. You’re going to do stuff that helps you ignore these noisily competing parts of yourself to be more precise to the group. Bias vs noise.

Lastly, how attraction makes us biased, and what we sacrifice

The other series (here, and here) covers the biases involved in a bit more detail. But we can summarise here a little more succinctly, because I’ve since made a new pretty graphic that I want to put here:

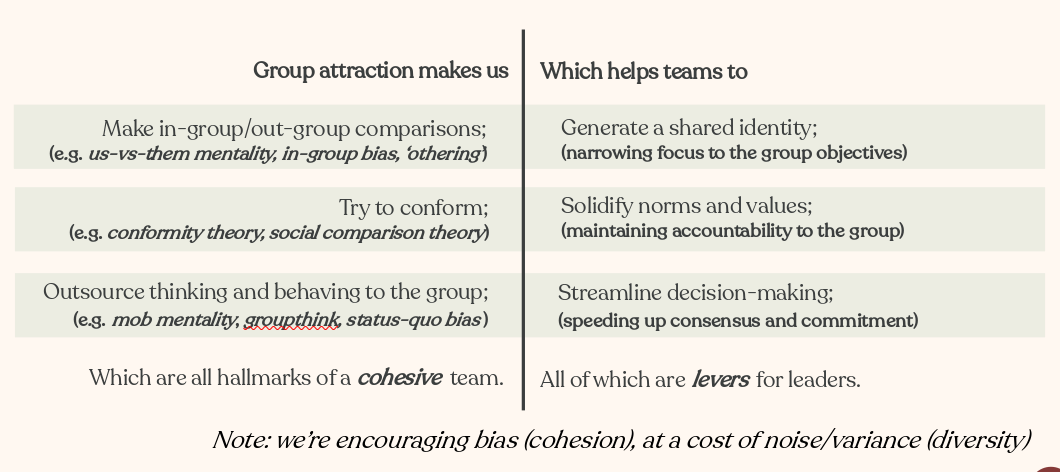

For every cluster of 'biases', there's a corresponding benefit. They're

ways of helping cut down all your competing priorities and desires to

the ones that will benefit the group. Bias over noise. Precision to the

group.

For every cluster of 'biases', there's a corresponding benefit. They're

ways of helping cut down all your competing priorities and desires to

the ones that will benefit the group. Bias over noise. Precision to the

group.

So, in-group/out-group biases, of which there are many, help us generate a shared identity. There can’t be an ‘us’ without a ‘them’. It’s completely necessary. And it helps us cut down all our competing priorities to the objectives of the group.

Conformity biases, again, of which there are many, help us solidify the norms and values of a group. It helps people understand how they should behave, and what kinds of interactions to prioritise, so we don’t have to try to select from our own enormous palette of individual priorities and behaviours.

And the scariest group of biases, in which we outsource our thinking and behaving to the group (like mob-mentality or groupthink), help streamline our group decision-making and get us actually doing things faster. It saves us having to arbitrate between all the different things we might want to do, and concentrate just on those that would benefit the group.

They’re all about ignoring our noisy inner-selves so we can be more precise to the group.

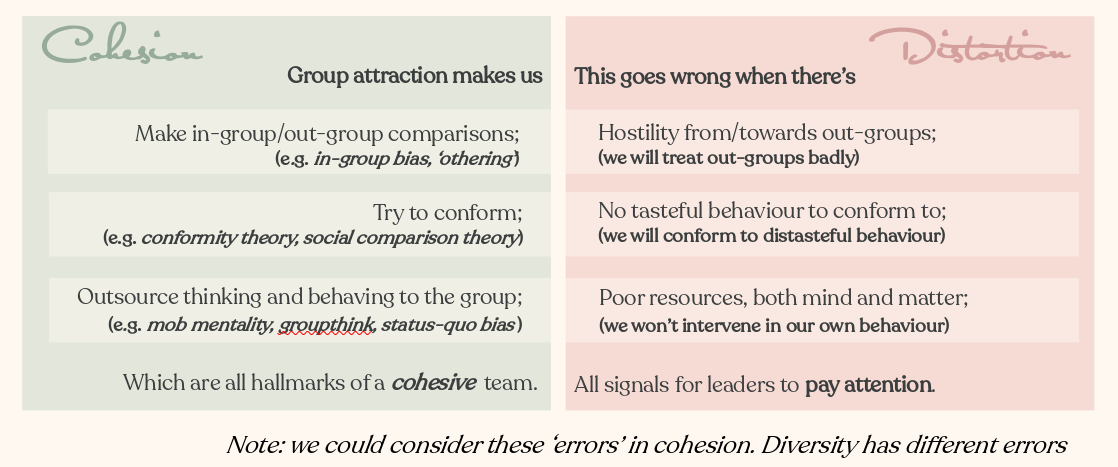

Now, there are obvious downsides to these. We’re afraid of biases for good reason. I talk about this in great detail in the final article in my other series on this, but I also have a nice new graphic for this, so I’ll put it here too:

For every cluster of 'biases', there are benefits, but also distinct drawbacks. Here are some, but I won't explain them in more detail here. You can read this for more detail there. What you should pay attention to is the fact that these are errors related to our attempts at precision. If we were going to go for noise instead---aiming to promote diversity, not group cohesion---then there would be different issues.

But there is another downside, which is that by prioritising group cohesion, we’re sacrificing diversity. Diversity of thought, and the highly-correlated diversity of background, has its own distinct benefits. And in the context of groups, diversity is the ‘noise’ to the increased cohesion that comes with ‘bias’.

Our noisy inner-selves might be competing, but they also have the potential to inject innovation. If we’re too precisely tuned to the group’s values, goals, and ways of being, then we’re going to miss angles and opportunities that different pieces of our individual identity, as well as our multiple group identities, might be more open to.

Relatedly, allowing for a bit more ‘noise’—idiosyncrasies and personal quirks—is going to make the group work better across a more diverse range of problems. A highly coherent group is going to perform really well at the things it’s coalesced around. But it’s going to be really fragile to changes in circumstance. A group that’s less coherent might not perform as well at certain things, but it’ll perform much better across a much wider range of stuff.

Outro

This is, in fact, why all these noisy inner parts and competing group identities exist. As I say over and over again, the world is a noisy place. So we have to be noisy people. If we weren’t we’d be trapped. Managing the need for noise with the need for bias is one of the main things the nervous system does.

Group identity, and the way we swap these in and out, is just one of the strategies it uses to solve the problem of a complex world. On one hand, these different identities let us benefit from bounded bias—knowing exactly who we are and what we do in a given group. On the other hand, having these multiple sources of identity injects just enough noise into our lives to keep us open-minded, flexible, and capable of responding to unexpected change.

It’s not about avoiding bias. It’s about finding the balance between strong group bonds and the individual noisiness that keeps us and our groups resilient in the face of change.7

I have no idea if this is true actually, but it seems plausible. They’re always jumping and throwing balls and stuff. ↩

Well, except as a strategy to mitigate the peculiarly Australian form of cultural racism, where we don’t mind as much as some other places if you’re coloured, but really get very stressed if you don’t fit in properly. ↩

This is ‘informative conformity’, and also Social Comparison Theory deals with this. Very similar, but ‘informative conformity’ is about looking ‘up’ to the group, or to influential members of the group, because you think they know better. Social comparisons more generally refers to times where you’re using others as a frame of reference for your own behaviour. This is more academic pedantry, really, but it is worth noting that there’s a difference between looking ‘sideways’ and looking ‘up’. If you think the other group knows better, then you might change your beliefs about stuff as well as your behaviour. But if you’re just looking sideways then you might keep your own beliefs, and only adjust your behaviour. ↩

Though cognitive dissonance isn’t responsible for everything. ↩

Also, I just figured out what the next article on this series will be, ha! ↩

See also, this article. ↩

I wanted to slip in a reference to Ben Scheider’s ‘attraction, selection, attrition model’ somewhere in this article. It describes how and why groups have this tendency to become more and more homogenous over time. But I couldn’t figure out how to work it in, so I’ll just stick it here. Interesting, and related, but not super related. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.