Catastrophic leadership is actually really hard

December 13, 2024

Excerpt: There’s this cluster of classic social psychology experiments from the 50’s through the 70’s that you’ll be presented with in documentaries and whatnot whenever groups of people are behaving crazily. You’ve probably heard of some of them. Milgram’s ‘shock’ experiments, or Zimbardo’s prison experiment, or Asch’s conformity tests, and so on. This is the first in a little series on group dynamics. Here we’ll talk about the classic experiments, and show that the kinds of catastrophic group dynamics people trot out to illustrate them are actually really difficult to achieve.

For group dynamics to produce really bad behaviour, you really need to work at it. You have to train your authority figures to be cruel, prevent dissent or disengagement, and intervene all the time to stop people fixing things. It’s hard.

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

There’s this cluster of classic social psychology experiments from the 50’s through the 70’s that you’ll be presented with in documentaries and historical novels whenever groups of people are behaving crazily. You’ve probably heard of some of them. Milgram’s ‘shock’ experiments, or Zimbardo’s prison experiment, or Asch’s conformity tests, and so on.

I’ll get into the details shortly for those who haven’t come across them before, but the basic idea is that humans will cheerfully engage in the most obscene behaviour if either:

- Everyone else is; and/or

- Someone charismatic/in authority tells them to.1

This, I should be honest, can be true, but you’ll find that things aren’t so straightforward as they’re often presented. And in concentrating on this, a more important point is often missed. Not only are the things that contribute to this bad behaviour are necessary features of any group, they’re also things that bring the best out of groups too.

So, this is the first in a series. Here we’ll talk about the classic experiments, and show that the kinds of catastrophic group dynamics people trot out to illustrate them are actually really difficult to achieve. In the next part, we’ll talk about how these dynamics actually underpin all groups, and then, in the part after that, how the best groups are both generated by and generate strong group biases. But, since this stuff does happen, I’ll finish off by walking you through what does have to happen to get some atrocities going.

The classic experiments: authority, obedience, and conformity

Even if you’ve come across these kinds of experiments before, it’s worth doing a little recap of how they’re typically presented before we get into how they actually pan out.

Arguably, the three most famous are Milgram’s, Zimbardo’s, and Asch’s.2 I myself came across these in my first year of psychology, and you could probably just read the articles I wrote then to get a sense of how they’re typically presented. But since I’ll almost certainly update those and pretend I was always as well informed as I am now, I’ll have another crack here. First, the three experiments and their headline findings, then the classic presentation of what it all means.

Milgram: Obedience to authority

Stanley Milgram’s experiments would never pass an ethics board today. He’d have you come in for the experiment, and trick you into thinking you were the lucky one. You got ‘randomly’ selected to be the ‘teacher’, and the other bloke got ‘randomly’ selected to be the ‘learner’. Your job is to use an ‘electroshock generator’ to teach the other bloke word sequences. Every time he gets one wrong, you shock him, and every time you shock him, you increase the voltage of the shock. Here’s what the device looked like:

Milgram and his shock device. You'd think that even if the last option, 'XXX', didn't make you think twice, the fact it's highlighted in red might have. Apparently Milgram thought so too. Not sure where these images came from, but they're used broadly online. If anyone has a copyright claim, do contact me.

As the experiment continues, and the shocks get stronger and stronger, the other bloke starts panicking. He’ll say things like ‘oh, God, please stop’ and ‘it’s too much, I want to stop’. But there’s a fella in a lab coat sitting behind you who’ll say things like:

- Please continue.

- The experiment requires that you continue.

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- You have no other choice, you must continue.

So you keep shocking the guy, and keep increasing the voltage. Eventually, he’ll be banging on the wall and complaining about his heart condition. The lab coated fella will keep pressing you if you complain, so you’ll keep going. Eventually, the ‘learner’ will fall silent, no longer answering. But you’ll keep shocking him for ‘getting the answer wrong’ until you get to the ‘XXX’ setting, and the lab coat calls the experiment.

What you wouldn’t have known is that the ‘learner’ was a confederate—an actor, in on the experiment. But since you didn’t know that, you still ‘killed’ him. And in the original series of these experiments, all participants went into the red-zone—to 300 volts, the beginning of the ‘Extreme Intensity Shock’. Worse still, 63% went all the way to the highest shock—450 volts, or the highest in the range of ‘XXX’.

Basically, your takeaway here will be something along the lines of ‘just because a person in a labcoat told you to do it, you’ll do it, even if it’s horrible’.

Zimbardo: The tyranny of authority, or, The Lucifer Effect

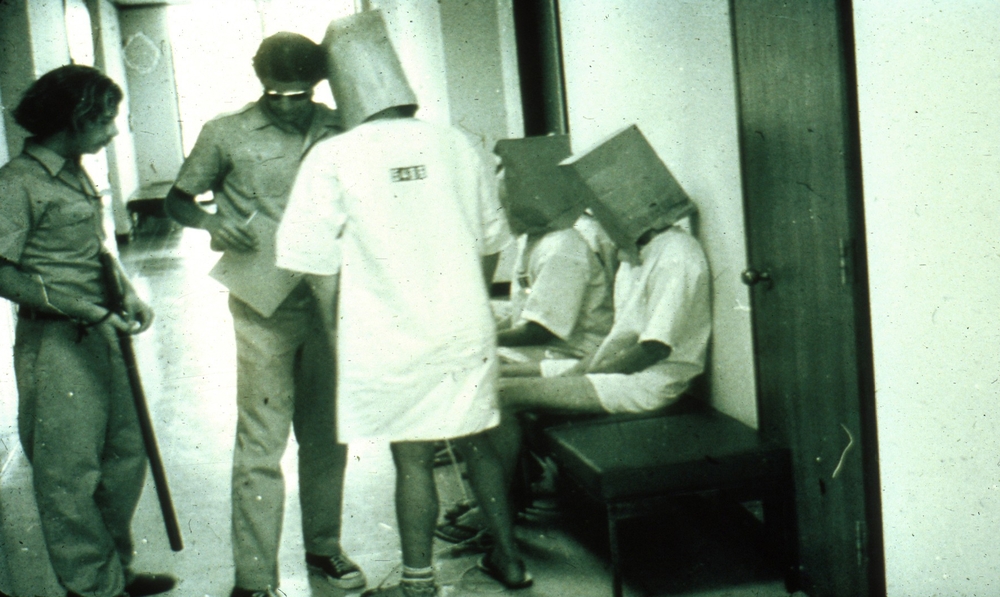

Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment is way worse than Milgram’s. Philip Zimbardo gathered a couple dozen students for a two-week experiment held in a basement of his office building. Half were assigned to the ‘guard’ condition and half were assigned to the ‘prisoner’ condition. Within 36 hours, things had deteriorated so badly that one prisoner had to be removed for the sake of his mental state, screaming things like “Jesus Christ, I’m burning up inside” and “I can’t stand another night! I just can’t take it anymore!”. 48 hours in, and the prisoners were rioting, while the guards used fire extinguishers to suppress them. By day three, prisoners were cleaning toilets with their bare hands, which may not have been so messy, given guards would often stop them using the bathrooms as a punishment. By day five prisoners could be found forced into nakedness, sleeping on concrete (mattresses were often removed as punishment) with bags over their heads and sleeping near buckets of their own excrement. By day six, Zimbardo was forced to end the experiment before it had even reached the halfway mark, given the escalating brutality of the guards, and the rapidly deteriorating conditions of the ‘prisoners’.

One of the less confronting stills from the prison experiment. Taken from the official site for the experiment, at which more ghoulish stills and videos can be seen.

More bizarre is the fact that no one requested to leave. This is a standard feature of psychology experiments—the withdrawal of consent. Anyone can leave at any time. But here, no one did. One went on a hunger strike (and was punished by being forced into a closet for the rest of the experiment). Others would submit requests for ‘parole’ (getting out but forfeiting the pay from the experiment) and would wait for their request to be heard. But very few simply said ‘I’d like to quit now’, as they could have any time, except those that had broken down so substantially that they were removed from the program. The rest simply waited for the ‘legal processes’ of the experiment. Absolute subjugation.

See, the ever escalating brutality of the guards was only one half of the story here. It wasn’t just that the guards encouraged each other to increasingly horrific abuses. It was that the prisoners accepted this completely voluntary abuse. After the day two riot, there were even in-groups and out-groups within the prisoners—the rioters and the ‘snitches’. And, by the end, in Zimbardo’s (copywriters’) words:

the prisoners were disintegrated, both as a group and as individuals. There was no longer any group unity; just a bunch of isolated individuals hanging on, much like prisoners of war or hospitalized mental patients. The guards had won total control of the prison, and they commanded the blind obedience of each prisoner.

From Zimbardo, you’re supposed to takeaway the idea that his team did:

After observing our simulated prison for only six days, we could understand how prisons dehumanize people, turning them into objects and instilling in them feelings of hopelessness. And as for guards, we realized how ordinary people could be readily transformed from the good Dr. Jekyll to the evil Mr. Hyde.

Asch: Conformity

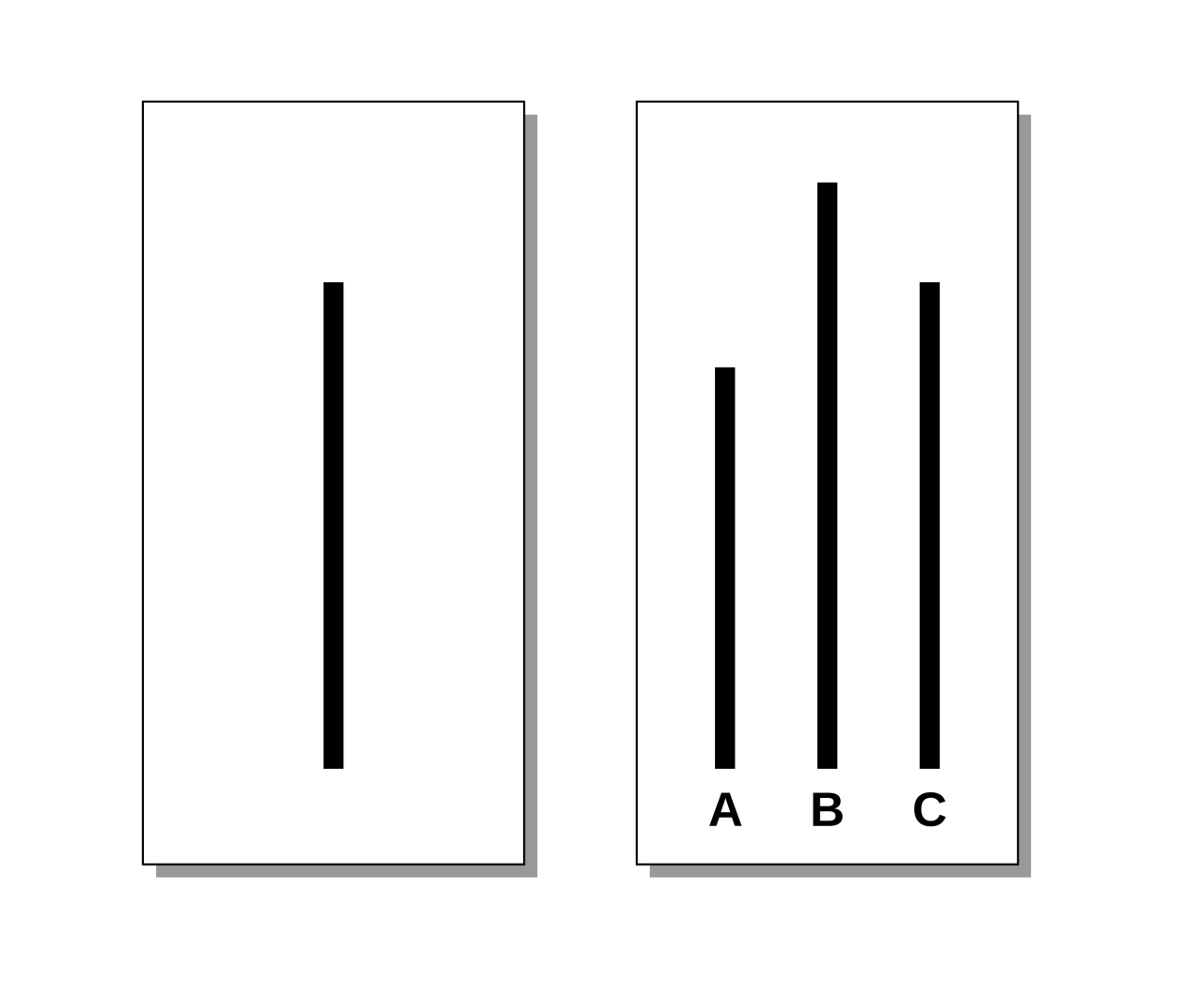

The last classic experiments concern Solomon Asch’s work on conformity. This one is more subtle, so not quite as popular as the others. But a modern take is making the rounds on Instagram, so I’ll explain both. Essentially, Asch would get a group of participants to sit in a room and view a line. Then, they’d be shown three lines, and would have to say, aloud, which of the three lines matched that first line they saw:

Asch's lines. On the left is the reference line which was shown first. On the right are the alternatives from which participants would have to say aloud which of the lines matched the reference line (it's C... or is it). Wikipedia.

But there was a trick. Only one of this group was a real participant. The rest were confederates. And after one or two gos where everyone would pick the correctly matching line, the confederates would eventually all pick the same incorrect line. So the test was to see how many of the real participants would go along with the group, even though they might not think the group was correct. And Asch found that about 35% of the time, participants would go along with the confederates, and select the incorrect line.

More recently, you might have seen some variation on Asch’s work on TikTok or whatever. Here’s a link to one. In this video, and ones like it, you see a crowded waiting room. This one is an opticians’. Every so often, you hear a ‘beep’, and everyone stands until the next beep, when they’ll sit again. These are our confederates. Our naive participant comes in and soon starts to join in—standing on the beep and sitting on the next beep, just like everyone else. Then, one by one, the confederates are all called out until it’s just our poor participant, standing and sitting obediently to the tyrannous beeping. And then new participants are led in, who also begin to stand and sit at the beep, following the cues of our poor original participant.

The takeaway from all this sort of thing is that, when confronted with the behaviour of others, even when it’s obviously absurd, we’re likely to just go along with it anyway.

Bad leadership and worse group dynamics

These experiments are held out as examples of how easy it is to create catastrophic group dynamics. Asch tells us that we will conform to the behaviour in others, even when conforming would be strange indeed. His conformity experiments influenced Milgram, who went on to show us how this is strengthened when obedience to authority is at play, rather than mere conformity to your peers. And Zimbardo showed that these things could be catastrophic, not just for those obedient to authority, but also the authorities themselves. All in all, a terrifying picture.

And those are just the foundational works. There’s this disorganised potpourri of findings people will use to add weight to the point. You can safely skip reading them if you like, since nothing in the rest of the article rides on your reading them, but to illustrate the ones military ethicist Dennis Vincent thinks are most common:

- Festinger’s 1954 Social Comparison Theory, which I’ve talked about elsewhere, adds to Asch’s conformity theory, demonstrating that we don’t just do what others do, but rather use others to judge ourselves.3 If others are behaving better than ourselves, we also strive to be better (so long as they’re not too much better). But if others are behaving worse, then we’ll bring ourselves down to their level. This isn’t just true of our behaviour, but also of our attitudes to things; or

- Festinger and the boys’ 1952 De-individuation, where we lose some kind of awareness of our selves in a group—our individuality and autonomy, or our ability to engage in self evaluation; or

- Festinger’s 1957 Cognitive Dissonance, where we do really weird stuff when we believe or think two things that oppose each other, like when smokers will say things like ‘we all have to die from something’, implying that the vicissitudes of lung cancer, or the long slow suffocation from respiratory illness are somehow preferential forms of death because while they know smoking is ridiculous, they also know they can’t stop. Or, Festinger liked to point at cults, in which people often ignore evidence that the group is ridiculous because they know they won’t leave; or

- Darley and Latane’s 1968 Bystander Effect, where the greater the number of people that are near us during an emergency, the less likely or slower we’ll be to intervene; or

- Samuelson and Zeckhauser’s 1988 Status Quo Bias and Janis’ 1972 Group Think (1972), where we’ll prioritise consensus and group norm cohesion, to the detriment of our mental efficiency and ability to test reality; or

- Stoner’s 1961 Risky Shift, where groups are more likely to make riskier decisions than individuals would; or

- Levi-Strauss’ 1952 Othering, where we might use a difference between people to create an in-group (‘us’) and and out-group (‘them’). And Kelman’s 1973 advance on othering, Dehumanisation, in which we talk about and treat ‘them’ in a way that strips them of their humanity. Or, Faure’s 2008 addition, Demonisation, where we come to perceive ‘them’ as inherently evil.

And these are just the ones that appear on my lecture slides for ethical leadership. I could go on, there are at least 200, but I’ll spare you.4

The summary you’ll get, regardless of which of this social psych fruit salad you’re served, will be much the same as you get with the three classic experiments we went through. When we’re in groups, those in authority are balanced precariously atop a collection of biases that threaten to suck them into a maelstrom of abuse. And those poor fools obedient to the group find themselves weaving delicately between a collection of biases that threaten to plunge them into an abyss of complicity and moral decay.

And we’d be remiss if we failed to include Hannah Arendt’s takeway from her examination of the Nazi logistician Adolf Eichmann—what she called the banality of evil:

The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

We’re all just a hair trigger away.

It’s never easy to get people to do this stuff

Alright, so I’m obviously playing this up a little. Most people won’t be quite this on the nose. But I don’t think I have ever sat through a lecture where Milgram was explained without hearing someone say something along the lines of:

just because a man in a white coat told them to do it…

And that ‘just’ is doing an incredible amount of work. Because in any given example of catastrophic group dynamics people trot out to illustrate these things, you’ll notice that people never just did anything. There’s always some enormous number of immense and complicated pressures that led people to behave in this way. And more, you’ll notice what Arendt herself would have told you if anyone actually read her book:

[U]nder conditions of terror most people will comply but some people will not, just as the lesson of the countries to which the Final Solution was proposed is that “it could happen” in most places but it did not happen everywhere. Humanly speaking, no more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a place fit for human habitation.

You can see this even in our classic studies.

Asch’s conformity effects aren’t very dramatic

In Asch’s original paper he points out the large variation in conformity. He ran 50 people through his paradigm and around a quarter never gave in. Another quarter-ish only confirmed a couple times. Only about a third ever went above half the time, and only one conformed on every trial.

Asch then identifies a few different reasons for conforming. Some truly conformed. But others had something of a crisis of confidence—coming to suspect something was wrong with their eyes. Weirdly, another group—comprised largely of high conformers—weren’t aware their answers were wrong. They had a ‘distortion of perception’, in Asch’s words, and had come to truly believe the majority opinion was the correct one.

This isn’t exactly reassuring, but it certainly indicates that conformity is not quite so common as one might think. The worst offenders seem to be victim to some kind of Müller-Lyer effect or something. And even in a super low-stakes environment, where it costs almost nothing to avoid the social awkwardness of calling everyone else in the room an idiot by lying about the line, most of the rest either didn’t or only hesitatingly went along with the crowd.

Asch himself makes this clear in his original paper. He makes a big deal of ‘independence’ (not conforming) over ‘yielding’ (conforming), because most participants were independent most of the time. So you won’t be surprised to find out that:

Milgram’s shock-maniacs barely existed

In Milgram’s own papers, he points out that:

The experiment is sponsored by and takes place on the grounds of an institution of unimpeachable reputation, Yale University. It may be reasonably presumed that the personnel are competent and reputable.

and

There is a vagueness of expectation concerning what a psychologist may require of his subject, and when he is overstepping acceptable limits. Moreover, the experiment occurs in a closed setting, and thus provides no opportunity for the subject to remove these ambiguities by discussion with others. There are few standards that seem directly applicable to the situation

and

The subjects are assured that the shocks administered to the subject are “painful but not dangerous.”

and

Through Shock Level 20 the victim continues to provide answers on the signal box. The subject may construe this as a sign that the victim is still willing to “play the game.” It is only after Shock Level 20 that the victim repudiates the rules completely, refusing to answer further

Even the paper isn’t convinced that the participants should have had second thoughts. And even with all this, Milgram points out that people were extremely reluctant to continue shocking the participant, often displaying signs of extraordinary stress:

There were striking reactions of tension and emotional strain. One observer related: I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse. He constantly pulled on his earlobe, and twisted his hands. At one point he pushed his fist into his forehead and muttered: “Oh God, let’s stop it.”

or

Profuse sweating, trembling, and stuttering were typical expressions of this emotional disturbance … the regular occurrence of nervous laughter, which in some [participants] developed into uncontrollable seizures

Now, true replications of Milgram’s experiments are basically impossible because no ethics review board would let you do it. But some points from the literature around his ideas are worth noting.

Firstly, for even the most basic test of whether something like this was statistically significant, you’d be wanting a sample size at least double that of Milgram’s initial experiment, and about 10 times as many as in his follow ups.5 If you have too few people then you’re likely to over-estimate the likelihood of an accident.

And Milgram’s results might very well have been an accident, because Gina Perry, on examining his studies, found a:

troubling mismatch between (published) descriptions of the experiment and evidence of what actually transpired.

with special mention of the lengths the lab coat would go to get the people to continue; and

only half of the people who undertook the experiment fully believed it was real and of those, 66% disobeyed the experimenter

indicating that some substantial proportion of our shock-maniacs didn’t actually believe that they were doing any serious shocking, and those who did were more likely to stop, not keep going.

Lots of people have replicated Milgram’s basic finding, that slightly over half of people will deliver high levels of shocks, but only in experiments that actually do pass ethics review boards. So, you have Jerry Burger’s for example, who halted his experiment at 150 volts—what in Milgram’s experiment would have been merely a ‘Strong Shock’ and well away from the red zone, which doesn’t seem like it’s testing anything other than whether people will participate in slightly unpleasant experiments.

And lastly, many people, even Milgram himself, have found that as soon as you put a dissenter in the room, the willingness to continue delivering shocks diminishes to near zero.

It’s not that no-one will show an amazing willingness to be obedient to authority in disturbing situations. It’s that maybe a tiny number will, but you’ll have to work damn hard to get them to.

Zimbardo was a lunatic

Look, Zimbardo’s ‘Stanford Prison Experiment’ is a cult classic. It was a hit in the post-counter-culture era, and a hit again after he re-published a sort-of diary of the events in the 2000’s as an airport book. It’s sexy, in a morbid kind of way.

But his account of it is very different from everyone else’s. Everyone else is very worried about Zimbardo and his ‘experiment’, because the experiment absolutely wasn’t an experiment. It doesn’t really seem like it was designed to test whether these conditions might arise, but to actually make them arise.

Luckily for us, a recent paper goes through, not only these concerns, but also more recent evidence that:

- Zimbardo and his team actively trained his ‘guards’ to behave the way they did; and

- Zimbardo and his team actively conditioned the prisoners to believe that they couldn’t leave.

Both of which, just by themselves, seem like they could entirely explain the guards’ abhorrent behaviour and the prisoners’ strange compliance. But let’s look at some excerpts:

Erich Fromm (1973) pointed out (a) the unethical nature of the harsh conditions imposed on the prisoners, (b) the fact that the personality pretests administered to the volunteers might not have detected a predisposition among some of the subjects for sadistic or masochistic behavior, and (c) the confusing situation for participants created by mixing realistic prison elements with unrealistic ones

and

Fromm also argued that because “two thirds of the guards did not commit sadistic acts for personal ‘kicks,’ the experiment seems rather to show that one can not transform people so easily into sadists by providing them with the proper situation

and

Banuazizi and Movahedi (1975) … provided 150 college students with [various collateral used to recruit and inform the participants] Of the students tested, 81% accurately figured out the experimenter’s hypothesis (that guards would be aggressive and that prisoners would revolt or comply), and 90% predicted that the guards would be “oppressive, hostile, aggressive, humiliating“

indicating that the participants probably also knew this, and this would have influenced their behaviour, rather than it being a natural outcome (i.e. a demand characteristic); and

Alex Haslam and Stephen Reicher, conducted a prison experiment similar to the SPE in collaboration with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC; Haslam & Reicher, 2003; Reicher & Haslam, 2006) … Reicher and Haslam concluded that “people do not automatically assume roles that are given to them in the manner suggested by the role account that is typically used to explain events in the SPE”

Critically, “neither Haslam nor Reicher took on a leadership role in the prison or provided guidance for the guards as Zimbardo had done in the SPE”.

And so on, and so on. But the real juicy stuff was in the archival material that came out later:

Zimbardo confided to the future guards that he had a grant to study the conditions which lead to mob behavior, violence, loss of identity, feelings of anonymity … [E]ssentially we’re setting up a physical prison here to study what that does and those are some of the variables that we’ve discovered are current in prisons, those are some of the psychological barriers. And we want to recreate in our prison that psychological environment. (“Tape 2,” 1971, pp. 2–3 of the transcript)

and

Zimbardo explained to them during the guard orientation … We can create boredom. We can create a sense of frustration. We can create fear in them, to some degree. We can create a notion of the arbitrariness that governs their lives, which are totally controlled by us, by the system, by you, me, [the warden]. They’ll have no privacy at all, there will be constant surveillance—nothing they do will go unobserved. They will have no freedom of action. They will be able to do nothing and say nothing that we do not permit. We’re going to take away their individuality in various ways. They’re going to be wearing uniforms, and at no time will anybody call them by name; they will have numbers and be called only by their numbers. In general, what all this should create in them is a sense of powerlessness. We have total power in the situation. They have none. (Musen, 1992, 5:07–5:44; Zimbardo, 2007b, p. 55)

and

I have a list of what happens, some of the things that have to happen. When they get here, they’re blindfolded, they’re brought in, put in the cell or you can keep them out in the hall I imagine, they’re stripped, searched completely, anything that they have on them is removed. (“Tape 2,” 1971, p. 5 of the transcript) The warden was reading a list handwritten by Zimbardo entitled “Processing in—Dehumanizing experience,” which indicates, for instance, “Ordered around. Arbitrariness. Guards never use name, only number. Never request, order” (“Outline for Guard Orientation,” n.d., p. 1).

and

Zimbardo and the warden thus set the number of counting sessions per day and designed them as a mix of boredom, humiliation and vexation. They determined the number of visits to the toilet and the maximum time prisoners could spend there (“Tape 2,” 1971, p. 16 of the transcript). They proposed to the guards to privilege the docile prisoners and to constitute “a cell for honor prisoners” (p. 22 of the transcript), which the more zealous guards did. They also suggested to the guards to be sarcastic or ironic, and to humiliate the prisoners by depriving them of their privileges, lengthening the counting sessions, opening their mail, having them clean their cells or inflicting meaningless punishments on them

and

The experimenters asked the guards not to follow their instinctive reactions but to play a specific role. Guard 11, reported, for example, at the end of the experiment, that several times, “the warden or Prof. Zimbardo specifically directed me (us) to act a certain way (ex. hard attitude Wednesday following Tuesday leniency)” (Guard 11, 1971, p. 1). T

and, contrary to Zimbardo’s claims that prisoners could leave any time:

The protocol he submitted to Stanford’s ethics committee, on July 31, 1971, stated that prisoners would “be led to believe that they cannot leave, except for emergency reasons. Medical staff will be available to assess any request to terminate participation … Prison subjects will be discouraged from quitting” (Human Subjects Research Review Committee [Non-Medical], 1971, p. 2; last sentence quoted in Bartels, 2015, p. 47). The archival material reveals that the prisoners had in fact only three ways of getting out: falling ill, having a nervous breakdown, or obtaining a special authorization from the experimenters.

Look. It goes on and on. Seriously, read it. The point is, Zimbardo’s ‘prison experiment’ wasn’t a prison experiment. It was a ‘teach some people to abuse others, and stop those others from leaving, and then write lots of papers about how terrible things get especially as we keep intervening to make things worse’.

Outro

And that seems like a good place to call it. Because Zimbardo’s experiment is the most accurate portrayal of the kinds of catastrophic group dynamics that come out of this corner of social psychology. Accurate not only in the ways people will behave, but also accurate in the factors that have to come together to make them behave that way.

You have to train your authority figures to be cruel. You have to stop people from being able to leave or cease participating. You have to screen out dissenters. You have to do it over long periods of time and with an intensive level of engagement. And you have to constantly intervene to stop people’s better judgement getting in the way of the terrible goings on.

It’s actually really hard to be a catastrophic leader.

Read on to find out how how the same factors at play here don’t just make for good group dynamics, but all group dynamics. Then you can read about how the best groups both generate and are generated by the strongest group biases. And finish the set by finding out what does have to happen to get people really stuck in to some outrages.

You might also see my article on successful prophets, which comes at this from another angle. ↩

There is also the Good Samaritan Experiment which I am not super familiar with, but I doubt it would be free of the problems I describe below. ↩

I should point out that Social Comparison Theory and Asch’s conformity findings aren’t exactly in line with one another. Social Comparison Theory tells us that when we’re uncertain about something, we first observe the thing. If we can’t observe the thing, or the thing is confusing, then we turn to others to see how they deal with the thing. Asch’s experiments are kind of the wrong way around—here people are confused about the thing because of others, not because of the thing. Maybe I’ll explore why this might matter in a different article, because for this article it doesn’t and you probably aren’t read in enough to think that ‘reality testing’ and ‘social reality testing’ are importantly different. ↩

And, frankly, because I just realised that rolling through each of these would make a fabulous little article series. ↩

I didn’t calculate this, but if I remember right, the sample size you’d need for a simple one- or two-tailed t-test for a medium effect at normal statistical power (.8 or so) with the usual 95% probability level is over 100, and Milgram only had something like 40. Less in his follow ups. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.