Useful groups are biased groups

December 27, 2024

Excerpt: There’s this cluster of classic social psychology experiments from the 50’s through the 70’s that you’ll be presented with in documentaries and whatnot whenever groups of people are behaving crazily. You’ve probably heard of some of them. Milgram’s ‘shock’ experiments, or Zimbardo’s prison experiment, or Asch’s conformity tests, and so on. This is the second in a third on group dynamics. Here we’ll talk about what makes our attraction to groups stronger, as well as what makes people participate in groups, and how all our group biases make sense in the context.

Ideology

The strength of our attraction to a group is a function of how different a group is from other groups in ways that we feel like we are, or like we want to be. Our participation in the group depends on how we see it benefitting us, and see us benefitting the group. The stronger both are, the stronger our biases to stay engaged.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

There’s this cluster of classic social psychology experiments from the 50’s through the 70’s that you’ll be presented with in documentaries and historical novels whenever groups of people are behaving crazily. You’ve probably heard of some of them. Milgram’s ‘shock’ experiments, or Zimbardo’s prison experiment, or Asch’s conformity tests, and so on.

I talk about them in detail in part one of this series, but the basic idea is that humans will cheerfully engage in the most obscene behaviour if either:

- Everyone else is; and/or

- Someone charismatic/in authority tells them to.

But, part one also walks you through how, although this is sometimes true, you have to really work at it to get people to behave in this way.

More to the point, as I explain in part two, the same group dynamics that underpin bad group behaviour actually underpins all group behaviour. The good groups too.1

Trying to avoid group biases is the same thing as trying to avoid groups. And you probably don’t want to avoid groups. Probably, you want to know why you’re attracted to groups, or how to make your group better. And for that we want to use our group biases, not avoid them. So, that’s what this article is about. And, in case you’re suspicious that someone really is working at getting some obscene behaviour happening, I guess we should probably look at that too (although I didn’t quite get there in this article, for that see the next one).

Making strong group dynamics

Obviously, it’d be helpful if you read part one and part two, but since you almost certainly won’t I’ll walk you through the relevant bits first.

Social scientists love endless lists of biases. Probably because, as the entire discipline of behavioural economics discovered, it’s much easier to call something a bias to explain your weird results than it is to admit that you screwed up your theoretical reasoning or experimental design.

When it comes to groups, you’ll probably have heard of some of these. Mob mentality. Group think. The bystander effect. Conformity theory. Status quo bias. In-group bias. The bandwagon effect. And so on and so on.

Now, these biases are all real effects. But as I complain about elsewhere, we’re not going to get much done if we’re trying to work our way through a list. Actually, what’ll happen is we’ll tend to concentrate mostly on how they go wrong, missing the times they don’t surprise us. Instead, we want to think about what’s going on underneath the biases. Then we’ll start to see what they’re doing right.

Generally speaking, we have biases because they help us reduce the errors we make. We can’t work out how to be around every new person from scratch, so we create social stereotypes to help us have a sense of where to start.2 Similarly, you wouldn’t have time for much else if you tried to work out the relationship between you and everyone who might impact your life individually, so you group people into social categories. Then, we can evaluate how similar or different we are from groups of people, and go from there.

Groups need to be distinct in ways we like

The theory that most neatly captures these dynamics is social identity theory3. Social identity approaches tell us that, on the other side of all this social stereotyping and categorisation, sits our own personal identity. We categorise people according to how distinct they are from us. Or, put another way, we sort ourselves in and out of these categories based on how we would like to distinguish ourselves from others. Like:

I’m not just Dorian, I’m Dorian the Australian. The Sydney-sider. The ex-pat in the UK. The ex-University student. The academic. The millenial. The plant daddy. And so on … these self-identifications are also social identifications … we each have all these social categories orbiting around us … The question is why? What makes us like some categories, dislike others, and slide between the rest? … Social identity theorists would tell us that the thing that makes us category-jump are the distinctions between them. Like, in the UK, I am Dorian the Australian. I place myself in that category to distingish myself from the British and other ex-pats roaming this soggy landscape. But in Australia, I place myself in the Sydney-sider category to distinguish myself from those pesky Melbournites.

What seems to make us want to identify with one group over another are the positive distinctions it has: the way it’s distinct from other groups in a way that appeals to our personal identity or sense of self.

But groups also need to stand out from other groups

So we’re going to feel drawn to a group that is distinct from other groups in ways we like. But we need a bit more than that. We also need chances to compare the group with other, similar groups. It’s not just the positive distinctions our group has for us, but also how distinct our group is from other groups.

It wouldn’t mean anything for me to call myself a ‘Sydney-sider’ if Melbourne was only different in name and place. It’s also that Sydney has better beaches, a better harbour, better brunch spots, better coffee, and weather that actually encourages you to go outside to enjoy all these things. Sydney has lots of things that distinguish it from Melbourne, so it becomes a useful distinction. In comparison, calling myself a Sydney-sider in the UK doesn’t make so much sense. To people in the UK, all these distinctions don’t mean anything. Both Sydney and Melbourne have better beaches, scenery, brunch, coffee, and weather than the UK. So I just call myself Australian instead.

See, we don’t want to just celebrate how well a group reflects who we are, we want to celebrate how much better a group reflects who we are than other groups.

Putting it together

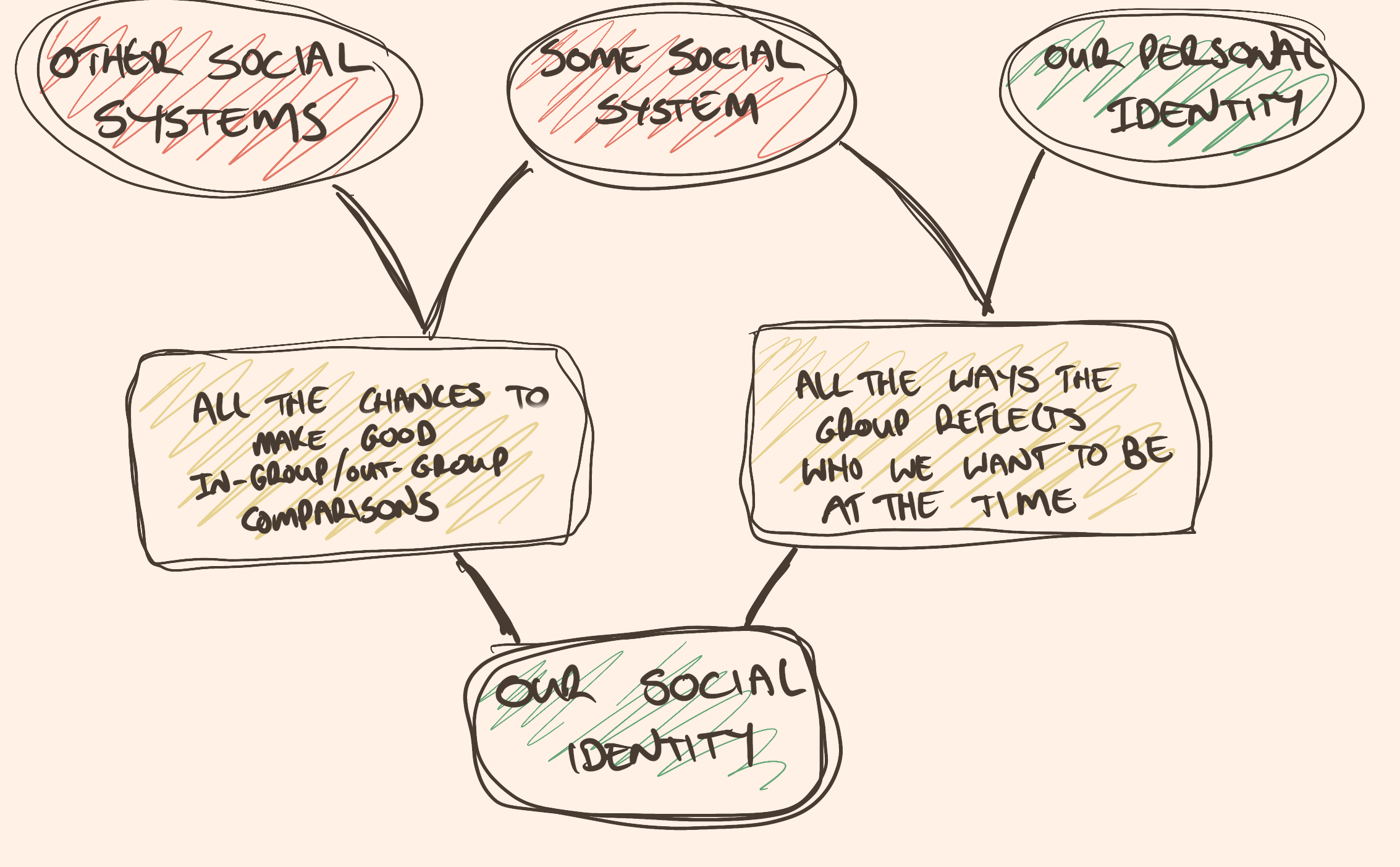

When you put it together, you’re looking at something like this:

A little sketch of the main things involved in the

creation of our social identity. All ways we the group reflects who are and

want to be at a given time, combined with all the chances we get to make

in-group/out-group comparisons that favour our group make up the strength

of how closely we identify with that group. The important thing is the

comparisons, otherwise all the ways the group seems to reflect us will seem

irrelevant.

A little sketch of the main things involved in the

creation of our social identity. All ways we the group reflects who are and

want to be at a given time, combined with all the chances we get to make

in-group/out-group comparisons that favour our group make up the strength

of how closely we identify with that group. The important thing is the

comparisons, otherwise all the ways the group seems to reflect us will seem

irrelevant.

Which makes what you’d want to concentrate on when you’re trying to work out what it is about a group that attracts us, or how to make a group stronger fairly straightforward.

First, all the traits of your group that make it appealing to people have to be very clear. Not just generally, but specifically for each person. What about the group reflects what that person wants to be?

Then there needs to be plenty of chances for people in the group to compare the group positively to others. What about your group is better than other groups? Even better if the traits that make your group appealing to people are the ways in which your group is distinct from the rest.

There are obviously many ways to go about working out what these distinctions could be. It’s fortunate for you, then, that I’ve written two articles on motivation. But one thing those articles make clear is that our affiliative motivations—motivations to belong, to be seen, to be validated by others, and especially, to have others share our goals—are some of the most powerful. So in some cases, all that needs to be highlighted is just how much of a group your group is.

And once you’ve started to do that, then the people themselves will do the work of strengthening their group affiliation for you. This is what the biases are doing—helping us understand ourselves in this sea of social categories. So:

when I do want to be identified with a group, I’m going to accentuate those distinctions. I’m going to make very clear all the ways this group I’m identifying with is different from other groups, and how similar the people in the group are to each other, including lil old me.

I’m going to make my own in-group/out-group comparisons. I’m going to modify my behaviour to better match the group. I’m going to outsource my thinking to the group, so the ways in which I think doesn’t interfere with the way the group thinks. And so on. All so that all the ways this group reflects my identity are made as clear as possible.

Aiming group behaviour

Alright. So we know what makes a group attraction strong. But groups aren’t very useful unless they’re grouped to do something. And there are some clear things that make us want to participate in a group.

Now, theories of what makes groups collaborate on things are… just terrible to read. The broad domain is called Social Capital, and you can just read the wikipedia page to see how convoluted it is. Several decades of intensive, argumentative, and unpleasantly baroque sociology have made for a very tangled web.

But, any attempt to talk about motivating groups to orient toward a goal without touching on the social capital within the group is missing the point of having a group. It’s all well and good to motivate individuals to achieve things. But you don’t really want your group to be acting like individuals, because as the last section makes pretty clear, acting like individuals divorces us from our groups. It’s the social capital that makes people achieve things for the group.

So in the twilight hours of this article4, I’ll brush through the sexier parts.

We are going to think about social capital as the stuff the group creates that the individuals wouldn’t have been able to create without the group.5 Obviously, you can think of the tangible ‘stuff’ a group might be better at creating. So, a group can pool more cash than any one person could alone. Or you could have group meetings at the houses of the richer members, where without those richer members, the group might not be able to gather. That’s part of it. But it’s also intangible stuff. So, you’re much more likely to get a job through your social networks than by applying for them. Or, within the group, you might be able to pool skills to finish a job that any individual member couldn’t.

Now, social capital motivates people in three ways. You can probabably guess the first. People love to know how being part of a group will benefit them. Access to stuff. Resources to do stuff. Social status.

The second is a little more oblique. People also love to know how what they can do for the group makes the group better. Unique skills the group doesn’t have. Contacts the group might not have access to. Bringing an energy that the people in the group appreciate.

A third is more oblique still. People love to know how being part of a group, and especially how what they can do for a group, will benefit other groups. Reputation that they can leverage to help others. Opportunities to connect those outside the group to those inside. Knowledge the group has that other groups can be introduced to.

Aligning whatever the group is doing to any of these things is going to keep people contributing to the goals of the group, regardless of how those goals might be motivating for the person individually. Possibly, even more so, because it also highlights how important the group itself is in the effort.

Once again, the obvious targets here are the more affiliative motivations, and the most active groups have these things in spades. Emotional support and trusting relationships both feel good and make the group more productive. Collaboration is a chance to experience feelings of relatedness, but also to demonstrate control and autonomy, all while doing things for the group. Reciprocity is one of our stronger social motivations, and sharing between people doesn’t just help people do things better, but also highlights what they have that’s valuable to the group.

But, if we want to get trendy with it, aesthetics are also a pretty significant mechanism. Our aesthetic dispositions—how being in a group makes us look, or how the group looks to others—are incredibly powerful levers. Since at least Bourdieu, huge amounts have been written about how the image and values a group projects to the world drive a great deal of our engagement with the group. You’ve almost certainly heard of virtue signalling, and if you’re of more of a conservative bent, luxury beliefs, and even if you aren’t panicking about these things, you can recognise how common these things are. Sharing the ideas associated with groups is one of the easiest ways to show our identification to it, and we do it all the time. When a group’s goals are aligned with the aesthetics people like about your group is a pretty surefire way to keep them engaged in what the group is doing.

Now you are a sociologist. Thank me later.

Outro

It’s a lot of text, but really, it’s very simple. We’re attracted to groups that are different from other groups in ways that we feel like we are, or like we want to be, anyway. The more a group makes those things clear, and the more chances we have to compare the group favourably to other groups, the more strongly we’ll be attracted to it. The more we’ll identify with it. Same thing really. But identifying with a group isn’t the same as participating in the group. For that, we need to see how the group benefits us, how what we do benefits the group, and ideally, how our participation in the group helps other people in other groups. And the stronger all these things are, the stronger our own group biases will become—all the better to help up position ourselves in a sea of possible groups, and keep us feeling productive as we participate in those groups. I’m almost mad it took me ~2000 words to get there, but I have to lecture on this later and those kids ask a lot of pesky questions.

My article on how Milgram’s experiments make people concentrate on the wrong stuff has ballooned into three articles now. I’ll stretch your patience and make it into four, because there’s still one thing worth talking about. The tendency for us to engage in group bias is a natural function of how we navigate our social identity, and they help us make our groups both better and more productive while doing whatever thing our group is supposed to be doing. But as part one demonstrated, this can go wrong. And we’ve talked about how to aim a group, but not what to do when a group is aimed in a bad direction. So. We’ll cover that in the next part.

See also this article, which gets at the same thing from a slightly different angle. ↩

For better, or worse. ↩

I’m not going to bother you with the fact that actually there are a number of distinct social identity approaches all vying for territory in the literature. It’s irrelevant to us. But you can see the footnotes of my last article for some pointers if you’re a hardo. ↩

I.e. as I get bored of writing it. ↩

These are usually called ‘public goods’, but I can’t think of a single reason why writing this into the article would be helpful so I’ll just put it down here for anyone following up. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.