Confirmation bias is all there is

October 18, 2024

Excerpt: Probably the most consistent theme in my articles is the fact that, although we like to think we’re rational creatures, we are far from it. One of the most obvious places this nervous and ill-fated obsession with rationality plays out for us is in the domain of bias. Since Kahneman and Tversky’s project on ‘cognitive illusions’ in the late 60’s, we haven’t just seen the terminology of bias spread into daily conversation (think ‘confirmation bias’), we’ve also seen this out-of-hand proliferation of all the various ways we’re biased. Over 200, listed on Wikipedia. In theory, you might think this kind of rigour is great. But in practice, what are we supposed to do with all of this? No one’s going around checking their every decision against this endless list. Well, maybe here, we have a way of narrowing things down.

Many cognitive biases seem like they can be boiled down to a handful of fundamental beliefs, and then belief-consistent information processing (i.e. confirmation bias).

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

Probably the most consistent theme in my articles is the fact that, although we like to think we’re rational creatures, we are far from it. Rather than try to fight it, around here I suggest we’re much better suited to trying to work with it. We hate the idea of that, though. We always have:

Historically, emotion has been viewed as the enemy of reason. Emotions make us act without thinking. Plato described emotion and reason as the horses that pull us in two directions. The biblical prophet Isaiah encouraged us to come together and reason, rather than act without thinking. A crime of passion was once a legitimate excuse for murder. Characters in literature are often overcome with emotion as a motivation for strange, plot-driving behaviour. Even modern approaches to therapy often position emotion as the enemy of rational wellbeing.

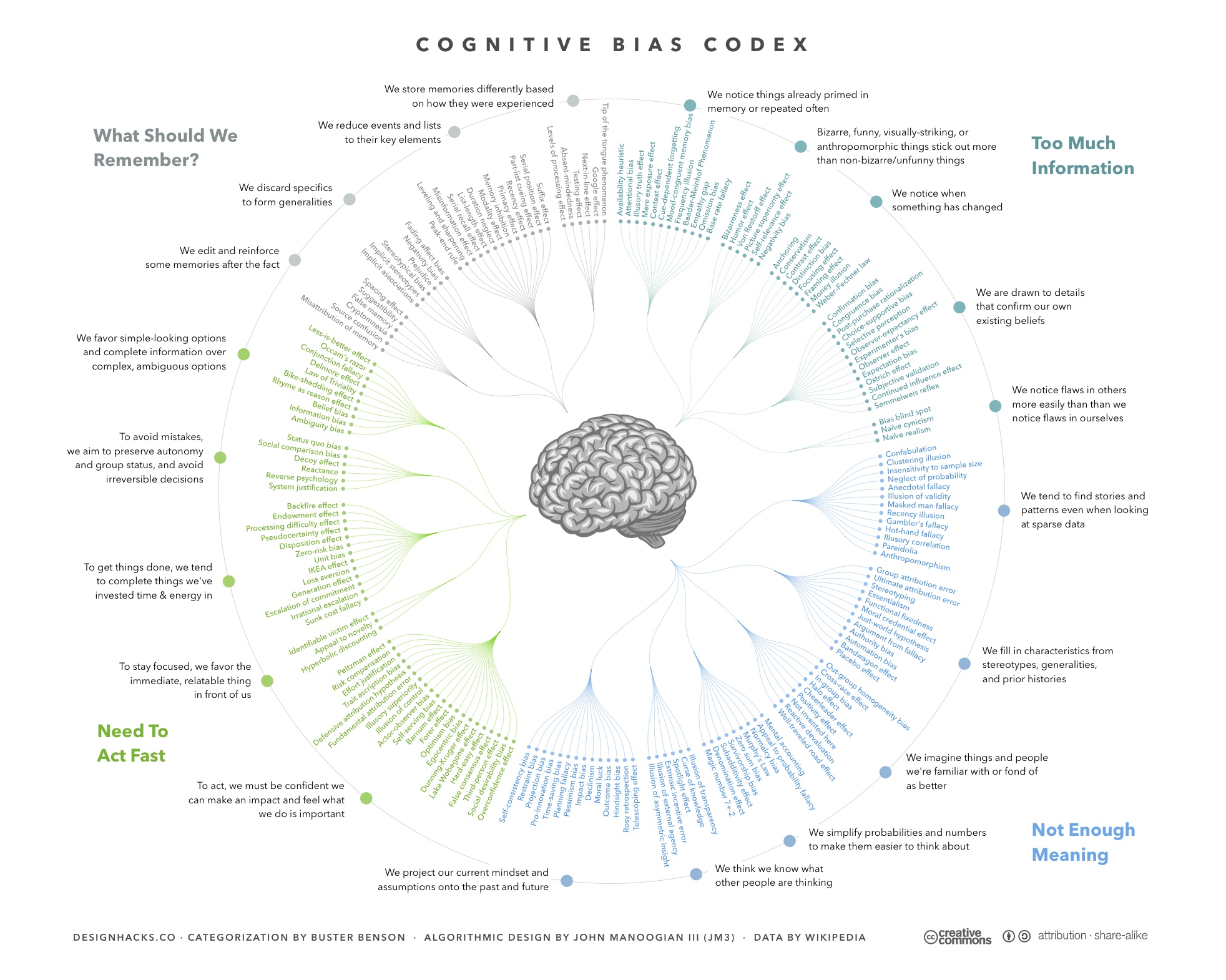

One of the most obvious places this nervous and ill-fated obsession with rationality plays out for us is in the domain of bias. Since Kahneman and Tversky’s project on ‘cognitive illusions’ in the late 60’s, we haven’t just seen the terminology of bias spread into daily conversation (think ‘confirmation bias’), we’ve also seen this out-of-hand proliferation of all the various ways we’re biased. If you go to Wikipedia’s list of cognitive biases, you’ll find a couple hundred of them. And the ‘cognitive bias codex’ on their explainer page is an overwhelming thing to gaze upon:

Wikipedia's 'Cognitive Bias Codex' is an overwhelming representation of the different biases and their various relationships.

Wikipedia's 'Cognitive Bias Codex' is an overwhelming representation of the different biases and their various relationships.

In theory, you might think this kind of rigour is great. But in practice, what are we supposed to do with all of this? No one’s going around checking their every decision against this endless list.

Behavioural economists have started to look up from their interminable listing to agree. And in that agreement, we start to see a new way forward. We don’t have to fight it or work with it. We can just, sort of, narrow things down.

The origin, and failure, of ‘bias’

Like the average person, behavioural economists also largely work off the assumption that humans are ‘rational actors’. They call it the ‘rational-actor model’. The idea, more-or-less, is that if you give a human a decision to make, they will decide by optimising for their preferences, weighing up the costs and benefits. You do stuff that does the most good for you, and the least bad. On this model, errors should only happen when you don’t have the right information to make the ‘rational’ decision.1

The ‘biases’ we’re talking about, all 200-or-so listed on Wikipedia, are times when we deviate from this model. When we make choices that are not optimised to our preferences, maximising benefit and minimising cost, despite having accurate information.

Biases, then, are deviations from a default state of rationality.

And the idea behind capturing them all is to help economists better model decision behaviour. Humans are rational, and so assuming they aren’t making any information-processing errors, we should be able predict their behaviour perfectly and design efficient behavioural interventions accordingly. But since we have all these biases, we also need to be able to sticky-tape them onto our model to capture the times when we’re deviating, or our interventions won’t be efficient.2

But with this extraordinary list of biases, we have to start wondering if something is up. You see:

There is no theoretical framework to guide the selection of interventions, but rather a potpourri of empirical phenomena to pan through.

Selecting the right interventions is not trivial. Suppose you are studying a person deciding on their retirement savings plans. You want to help them make a better decision (assuming you can define it). So which biases could lead them to err? Will they be loss averse? Present biased? Regret averse? Ambiguity averse? Overconfident? Will they neglect the base rate? Are they hungry? From a predictive point of view, you have a range of countervailing biases that you need to disentangle. From a diagnostic point of view, you have an explanation no matter what decision they make. And if you can explain everything, you explain nothing.

If your list of ‘deviations’ are getting in the way of your model’s ability to predict something, then maybe these aren’t biases at all. Maybe we’re not deviating from normal human behaviour, maybe these are deviations from the wrong model.

And these deviations are stopping us from being able to predict human behaviour. For example, this enormous study3 of almost 700,000 people looked at what kinds of behavioural interventions would make people more likely to get routine vaccinations. The results aren’t what’s interesting (to me). What’s interesting is that when they asked behavioural economists to predict which interventions would work best they couldn’t. More to the point, random lay people could (slightly). Your average joe was better than your well-informed scientist at predicting the effectiveness of these behavioural interventions. Knowledge of biases would appear to be a barrier to prediction.

This isn’t just troubling because our list of biases is making the list of biases useless. It’s also troubling because we’re entering the same territory that crippled the discipline of psychology. As one of the princes of behavioural economics, Richard Thaler, pointed out:

If you want a single, unified theory of economic behavior we already have the best one available, the selfish, rational agent model. For simplicity and elegance this cannot be beat … The problem comes if, instead of trying to advise them how to make decisions, you are trying to predict what they will actually do … Some people wrongly conclude from this that behavioral economists are just adding degrees of freedom, allowing us to “explain anything” … [but these are] not coming out of thin air to deal with some empirical anomaly, they are based on evidence about how people actually behave.

Just as psychology has no unified theory but rather a multitude of findings and theories, so behavioral economics will have a multitude of theories and variations on those theories.

Somehow, Thaler is spinning this as a positive. But this is exactly what led to the replication crisis—where the ‘multitude of findings and theories’ turned out to be largely impossible to reproduce and therefore weren’t theories or findings at all, but literally, as Thaler put it, “coming out of thin air to deal with some empirical anomaly”. Psychology was the worst hit of all the sciences in this regard. And somehow Thaler reckons that by copying this model of science they will avoid doing the exact same thing?

So what instead?

Really, the issue here is the focus on the biases in and of themselves. Rational or no, what we’re doing when we’re making decisions has nothing to do with bias. What we’re trying to do is minimise errors. But our processes of error minimisation are under no obligation to conform to the rational actor model. Indeed, the most comprehensive model for human behaviour as error minimisation indicates that the real world is only a secondary input into our decision-making. You see:

The brain instead attempts to predict its inputs. The output kind of comes first. The brain anticipates the likely states of its environment to allow it to react with fast, unthinking, habit. The shortcut basal ganglia level of processing. It is only when there is a significant prediction error—some kind of surprise encountered—that the brain has to stop and attend, and spend time forming a more considered response. So output leads the way. The brain maps the world not as it is, but as it is about to unfold. And more importantly, how it is going to unfold in terms of the actions and intentions we are just about to impose on it.

This isn’t avoiding bias. It’s injecting bias. We act based on our expectations, not on our calculations of cost-benefit. You know this. It doesn’t matter so much that some area of the city has the highest crime rate. What matters is that when you went there you haven’t had any problems.

We only calculate if our expectations fail dramatically enough for us to notice. This seems reasonable enough to me—the brain only has so much computational power. Trying to calculate a football’s trajectory to catch it makes less sense when we can, and do, employ a strategy that requires us to make no calculations at all but instead rely on our expectation that it’ll fall somewhere along the path it flew off on. And indeed, a lot of brain science, and other modelling work pays very close attention to this, and will inject bias into their models to deliver the lowest error (I explain this better here).

I say all this to provide some ‘rational’ evidence for this idea, but since we aren’t rational, I’ll make this even more intuitive. I talk about quite a few of these things this other article, but here, to keep things spicy, we’ll consider social stereotypes.

Social psychologists define a stereotype as a “fixed, over-generalized belief about a particular group or class of people”. We do this to quickly assess the kind of person someone is. And we do that for two reasons;

- we want to quickly figure out whether talking to them is a good idea; and

- we want to figure out the kinds of things we can talk to each other about.

One of the very first things we do, when we meet someone, is to engage in an almost ritualistic back-and-forth—what are you called, what do you do, where are you from. The point of this is less about the information as it is about determining what kind of person we’re dealing with. Because:

Stereotypes help us find the common ground. And this is true because stereotypes don’t materialise in a vacuum. Chances are that people will roughly adhere to a handful of stereotypes. These are impressed upon us by both our culture and our temperament. And if we didn’t adhere to any kind of stereotype, then every conversation would drag on forever as we tried to work out the other person from scratch.

Stereotypes are a collection of biases we inject into our behavioural responses to reduce error in our interactions. And sure, sometimes this means we don’t treat people as we should, but it also means we’re much less error-prone in our interactions than if we tried to work people out from first principles.

If you look at any of the 200-odd deviances listed on Wikipedia, you’ll notice the same thing. They’re all adaptive for the most part. It’s just that, under some contrived circumstances, they aren’t. Or, more precisely, they don’t make you do what behavioural economists want you to do to conform to their model.

Belief-consistent processing, not bias

Considering all this, it’s not surprising that a recent review has proposed that a truckload of the biases we’ve identified seem to boil down to:

- Some fundamental belief; and

- Belief-consistent information processing (i.e. confirmation bias)

I’ll let them explain:

We consider beliefs as hypotheses about some aspect of the world that come along with the notion of accuracy—either because people examine beliefs’ truth status or because they already have an opinion about the accuracy of the beliefs … It is irrelevant for the current purpose whether a belief is false, entirely lacks foundation, or is untestable. All that matters is that the person holding this belief either has an opinion about its truth status or examines its truth status.

They then go on to do an admirable job of pointing out that, on this account, all learning is more or less some kind of belief. They then explain that a huge slew of ‘biases’ seem to originate from some motivating belief (I’ve removed the references, FYI):

To date, researchers have accumulated much evidence for the notion that beliefs serve as a starting point of how people perceive the world and process information about it. For instance, individuals tend to scan the environment for features more likely under the hypothesis (i.e., belief) than under the alternative (“positive testing”). People also choose belief-consistent information over belief-inconsistent information (“selective exposure” or “congeniality bias”). They tend to erroneously perceive new information as confirming their own prior beliefs (“biased assimilation”; “evaluation bias”) and to discredit information that is inconsistent with prior beliefs (“motivated skepticism”; “disconfirmation bias”; “partisan bias”). At the same time, people tend to stick to their beliefs despite contrary evidence (“belief perseverance”), which, in turn, may be explained and complemented by other lines of research. “Subtyping,” for instance, allows for holding on to a belief by categorizing belief-inconsistent information into an extra category (e.g., “exceptions”). Likewise, the application of differential evaluation criteria to belief-consistent and belief-inconsistent information systematically fosters “belief perseverance”. Partly, people hold even stronger beliefs after facing disconfirming evidence (“belief-disconfirmation effect”; see also “cognitive dissonance theory”).

This is contiguous with the ‘predictive processing’ framework of what the brain is doing, from earlier. We have expectations. We look for those expectations to be borne out. Only when what’s happening violates those expectations dramatically, do we do something else. And, in the main, even if you don’t like the account from brain science, you’d be hard pressed to find any behaviour scientist that disagreed with the premise. Beliefs and belief-consistent processing are ubiquitous features of human behaviour.

What these authors add is that, rather than a grab-bag of biases and a similar range of related beliefs, maybe what’s going on is that there are a few fundamental beliefs, and many of the biases can be tied back to this small group. So, one belief might be that “My experience is a reasonable reference”, which seems to explain a good handful of biases (again I’ve removed the refs):

A number of biases seem to imply that people take both their own (current) phenomenology and themselves as starting points for information processing. That is, even when a judgment or task is about another person, people start from their own lived experience and project it—at least partly—onto others as well. For instance, research on phenomena falling under the umbrella of the “curse of knowledge” or “epistemic egocentrism” speaks to this issue because people are bad at taking a perspective that is more ignorant than their own. People overestimate, for instance, the extent to which their appearance and actions are noticed by others (“spotlight effect”), the extent to which their inner states can be perceived by others (“illusion of transparency”), and the extent to which people expect others to grasp the intention behind an ambiguous utterance if its meaning is clear to evaluators (“illusory transparency of intention”). Likewise, people overestimate similarities between themselves and others (“self-anchoring” and “social projection”), as well as the extent to which others share their own perspective (“false consensus effect”).

Or another could be “I make correct assessments” (refs removed):

Having the belief of making correct assessments also implies not falling prey to biases. Precisely such a metabias of expecting others to be more prone (compared to oneself) to such biases has been subsumed under the phenomenon of the bias blind spot. The bias blind spot describes humans’ tendency to “see the existence and operation of cognitive and motivational biases much more in others than in themselves”. If people start out from the default assumption that they make correct assessments, one part of the bias blind spot is explained right away: the conviction that one’s own assessments are unbiased. The other part, however, is implied in the fact that people do not hold the same belief for others. The logical consequence of people’s believing in the accuracy of their own assessments while simultaneously not holding the same conviction in the accuracy of others’ assessments is that people expect others to succumb to biases more often than they themselves do. Another consequence is to assume errors on the part of others if discrepancies between their and one’s own judgments are observed. The hostile media bias describes the phenomenon by which, for instance, partisans of conflicting groups view the same media reports about an intergroup conflict as biased against their own side. If people assume their own assessments are correct and, by nature of being correct their views are also unbiased, it is almost necessary to assume others (people/media reports) are biased if their views differ.

Teleological/agentic bias

Since writing this article, I’ve been just shitting all over the concept of bias. In articles, in the classroom, everywhere. It’s been quite cathartic. But the paper I describe above didn’t identify many bias clusters. Just the two above. So I thought I’d have a go at my own:

We believe things are caused by people

I wrote a whole article about how we probably over-emphasise coincidences. In there I describe how, when toast falls butter-side down, we assume it’s not random. Often we’ll say something like ‘the universe hates me’ or ‘Murphy’s law’.

This is an example of what is sometimes called the “teleological bias.4 Dolores Kelerman wrote a famous article called Why are rocks pointy?, where she describes children’s “promiscuous teleology”: in which “children were more likely than adults to broadly explain the properties of both living and nonliving natural kinds in teleological terms, although the kinds of functions that they endorsed varied with age”. For children, rocks are pointy for reasons—so animals can scratch, or so people can use them as tools.

The idea is now very popular in the cognitive science of religion. It’s put forward by people like Ara Norenzayan that, to be a little glib, we evolved to detect agents and purposes because assuming the rustling bush is a predator, and not wind, kept us alive.

Whether the argument is true or not, we certainly do seem to assume things happen for agentic reasons, and Wikipedia has a whole bunch of biases, including the teleological bias, listed under Causal Attribution that’s just asking to be grouped like the authors above suggest.

So, intentionality bias and fundamental attribution error are both teleological biases—we assume other people are doing unpleasant stuff intentionally, not accidentally. Or the just-world bias and proportionality bias are both examples of us ascribing big, agentic reasons for bad things.

Whether it was because rustling bushes contained lions or not, we have a fundamental belief that things happen for agentic reasons—entities are behind the stuff that happens to us, and the confirmation bias that accompanies that belief explains a whole slew of biases.

I like this one because it makes my ideas about abstractions as gods and ’spiritification’ even stronger.

Outro

The article is really just a first foray into the idea that perhaps all our biases stem from a handful of fundamental beliefs, and the confirmation bias (belief-consistent processing) that follows. But, as you can see from my brief example, it’s enough to give us a slightly better approach to tackling bias than an overwhelming list of them. If you can identify the fundamental belief, then you’ll immediately have some idea about what kind of biases you might have. And indeed, as they point out, it’s possible that only:

if people tackle the beliefs that guide—and bias—their information processing and systematically challenge them by deliberately searching for belief-inconsistent information, we should observe a significant reduction in biases—or possibly even an unbiased perspective.

It’s a big shift in the way we think about decision-making. It’s actually a challenge to the predictive processing account too. A core assumption of the framework is that we rationally process new information—when our expectations are violated, we update them truthfully. But here, it might be that we don’t. We update them with bias, based on our fundamental beliefs, built in.

Also, as the authors point out, this calls into question a lot of motivation literature. The rational-actor model, and many other models of human behaviour, assume that a lot of what we do is motivated behaviour. We want the world to be better for us. We want things to happen faster or in a more satisfying way. We want more things we like. That’s why we’re biased. But this approach is saying that maybe a lot of our behaviour is incidental. It looks like motivated behaviour, but is just a result of our blindness to information that isn’t in line with our beliefs. It’s a troubling concern, and one that’ll probably make a couple academic careers.

But, I think, largely this isn’t so much a day to day concern. Motivated or incidental, if what one is trying to do is respond accurately, then keeping their beliefs in mind is a way of getting a better handle on things than concentrating on the possible biases. More importantly, it makes my everything is an ideology and animals first narratives heaps stronger, and what’s good PR for my website is good PR for when you share my website.

Obviously, the complexity of the choice matters, as does what constitutes a ‘cost’ or ‘benefit’ and behavioural economists are silly about this too, but this is a different problem I won’t rehash here. ↩

Again, the issue of whether the modeller is accurately identifying the right ‘costs’ and ‘benefits’. See the previous footnote. ↩

The technical term, believe it or not, is ‘megastudy’. ↩

You’ll have to google that since Wikipedia doesn’t have a page for it yet and my Wikipedia-editing days are long behind me (although it is listed in their list of cognitive biases. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.