Bias vs Noise pt. I: Bias vs Bias

March 21, 2025

Excerpt: The perils of cognitive bias is a subject that’s dominated a substantial slice of social psychology, and appears in any leadership or personal development course as something to be avoided at all costs. It’s interesting, but it’s not actually that useful. You can’t sift through 200+ biases to work out what you might do wrong. The brain treats bias differently. Bias is a strategy to solve certain kinds of problems. Let me show you how.

The behavioural economists treat bias as an error. But the brain isn’t an economist. It’s more like a statistician, using bias as a trade-off. Bias ignores noise to see something more clearly, though of course, sometimes the noise shouldn’t be ignored.

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

One of my more popular ideas these last few months has been the idea that bias is good. The perils of cognitive bias is a subject that’s dominated a substantial slice of social psychology, and appears in any leadership or personal development course as something to be avoided at all costs. So people are often either upset that I’m saying it’s good or titillated by the subversiveness.

Now, I do kind of pose this in a subversive way. I pose a lot of things in a subversive way—hijacking, essentially, the sociology of the interesting. But I wanted to write an article explaining that this isn’t actually that subversive at all.

So, first I’ll talk about the classic perspective on cognitive bias, tell you why people, including myself, like it. But also why I think it isn’t really that useful.

Then I’ll talk about another way of thinking about bias, and how in some ways it’s more prevalent than the classic way. Not only that, but in fact its how the brain treats bias, and that seems much more relevant to me than the ‘classic’ view which absolutely does not.

Then, because as I wrote this, I realised I wouldn’t finish in time to publish it all this week, I’ll follow up with an article or two, and maybe an ongoing, irregular series, to show you how this more useful view of bias plays out in practice.

Edit: In fact, now there are a couple, you can find them collected here.

Let’s go.

The ‘classic’ approach to bias

There are two ‘classic’ approaches to bias. One is the academic version, and one is the pop-psych version. They’re very similar, but the pop-psych version often fucks it up. So I’ll present the fucked up version first, then correct it, then tell you where it is and isn’t useful.

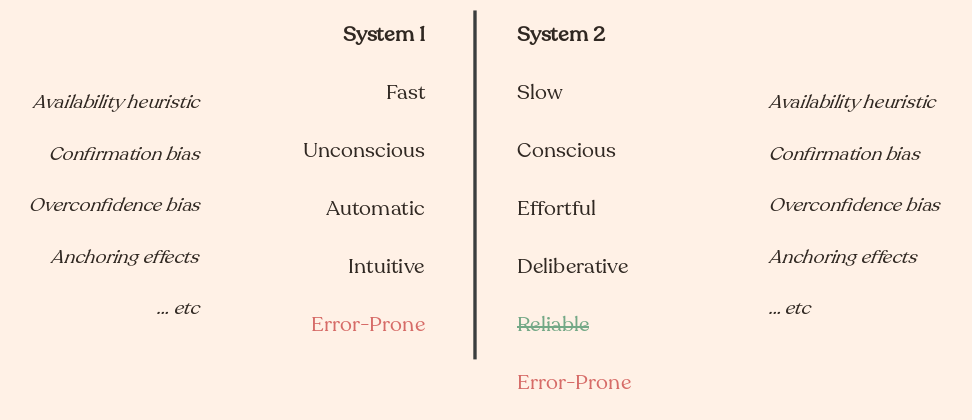

Dual process theories are this cluster of barely distinguishable theories that split human thought into two broad categories. Daniel Kahneman has the best known of these, so we’ll use his terminology since the differences in theory are too marginal for this article to get into. Kahneman calls them:

- System one is fast, unconscious, automatic, and intuitive.

- System two is slow, conscious, effortful, and deliberative.

So when you drive a familiar route and find yourself at the end with no memory of the drive, that’s System one—fast, automatic, unconscious. Or when you tell me what 1+1 is. Or read these words.1

When you’re driving to a new place, and you need to work out how long it’ll take and which route will have less traffic, that’s System two—deliberative, effortful, and slower. Or calculating 26*49. Or working out what these words mean, rather than just reading them.

Fast vs slow thinking, Kahneman called them, and it’s a pretty neat dichotomy if you’re going to put all human thinking in two buckets.

The popular, wrong version

It’s all too common to walk away from this idea of a ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ system of thinking with the idea that the ‘fast’ thinking is broken. That ‘fast’ thinking leads to all kinds of biases in decision-making—errors—that make our decisions problematic. So for example, you might be told about:

- the availability heuristic: where you base your gut decisions on the information available to you. So, people might be scared of flying planes because they’ve heard of plane crashes in the news, but they aren’t scared of driving even though that’s orders of magnitude more risky.

- confirmation bias: where you’re more sensitive to information that confirms your beliefs and ignore information that contradicts them. So people who get into the paleo diet2 will often speak about how we should keep our bodies in tune with our evolutionary past, but won’t really have thought much about what, in real terms, it does better than other diets.

- overconfidence bias: where we overestimate our abilities or knowledge. So, if you’re anything like me, you’ve heard of the footy players Lionel Messi and Christiano Ronaldo, but know very little else about soccer. They’re legends, on every t-shirt in every TV show that shows people in soccer jerseys.3 If I was forced to go to a game, obviously I’d assume their team would win. But I wouldn’t necessarily be right. GPTo1 tells me they’ve both lost about 15% of their games.4

- anchoring effects: where your initial impression of something colours how you treat it later. So, first impressions with people are a great example—if you liked or didn’t like them, it’ll be hard to shake that off as time goes on.

And so on. And the cure, on this faulty account, is ‘slow’ thinking. If you had people rationally think about these things, then you might be less error-prone. Slow thinking is more reliable, and helps you avoid the biases that ‘fast’ thinking stumbles into.

The also popular, but correct version

This actually isn’t how Kahneman, or indeed any other dual-process theorist frames these two ways of thinking. Fast thinking is prone to these kinds of biases, but so is slow thinking. In fact, I chose these biases specifically because slow thinking is in some ways more susceptible to them than fast thinking:

The correct interpretation of [System 1 and System 2](analects/dual-process-theories.md). Both suffer biases. Both are error prone. System 2, or 'fast' thinking, isn't more reliable than System 1.

The correct interpretation of [System 1 and System 2](analects/dual-process-theories.md). Both suffer biases. Both are error prone. System 2, or 'fast' thinking, isn't more reliable than System 1.

- You can’t really deliberate very well on data you don’t have access to, so your slow thinking suffers from availability heuristics just as much as fast thinking. You’d have to be aware that you didn’t have data you needed to do something about that.

- Confirmation bias affects what information you seek out when you’re trying to think more deliberatively too. Just because the bias might be unconscious doesn’t mean it doesn’t influence your conscious thinking.

- Overconfidence bias, like the availability heuristic, is about something to do with missing data. It’s not so important whether you make the decision fast or slow if you think you’re operating on the right kind of information.

- Anchoring effects are famous for their role in cash negotiations. Someone puts out a number and the result you end up settling on won’t go much higher or lower. Again, just because you’re not aware of the bias doesn’t mean it’s not influencing your deliberative thought processes.

Kahneman was upset about fast thinking. Fast thinking is particularly problematic for financial decision-making, and Kahneman was an economist, so he wrote a book that emphasises how fast thinking can fail us, and de-emphasises how slow thinking is subject to the same kinds of problems. But he did also spend some time pointing out that fast thinking is useful and slow thinking can fail too.

Where they’re interesting, and where they’re not

What Kahneman was mainly trying to do was to distinguish between heuristics—mental shortcuts—and biases—where these shortcuts lead us astray. So the availability heuristic from earlier is usually a good thing.5 If data is very available, there’s probably a reason to soak it up. Lots of break-ins nearby recently? That seems like it might be pointing to something worth paying attention to because local break-ins seem like they’re saying something about the safety of your neighborhood. But the fact that you’ve seen more plane crashes in the news media than car crashes isn’t so interesting, because it’s actually saying something about the news, not your likelihood of dying in a plane.

So a heuristic is a mental shortcut that usually does us good, and a bias is when this heuristic contributes to us making some kind of error. This idea that a bias is an error comes directly out of behavioural economics:

Like the average person, behavioural economists also largely work off the assumption that humans are ‘rational actors’. They call it the ‘rational-actor model’. The idea, more-or-less, is that if you give a human a decision to make, they will decide by optimising for their preferences, weighing up the costs and benefits. You do stuff that does the most good for you, and the least bad. On this model, errors should only happen when you don’t have the right information to make the ‘rational’ decision.6 …

Biases, then, are deviations from a default state of rationality.

And the idea is that behavioural economists can use this information to help model decision-making in people. If we can catch all the times where people make these deviations, then we can predict their behaviour better.

That’s the idea. In practice, no. In practice, what we’ve ended up with something approaching 300 individual biases that makes it increasingly difficult to predict behaviour.

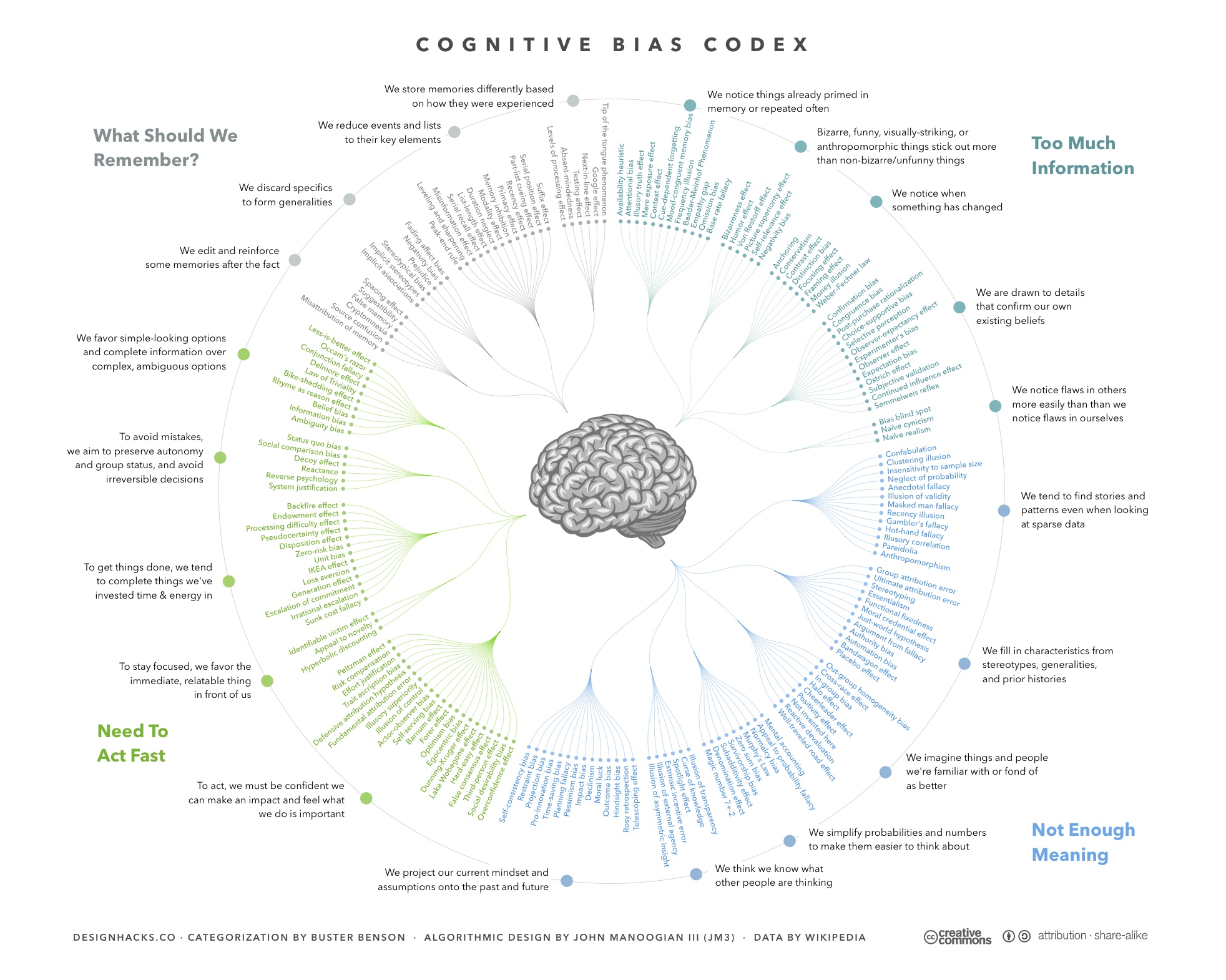

Wikipedia's '[Cognitive Bias Codex](analects/belief-consistent-information-processing.md)' is an overwhelming representation of the different biases and their various relationships. I think there are 180 or so here, and last time I saw a number reported in the literature it was around 260.

Wikipedia's '[Cognitive Bias Codex](analects/belief-consistent-information-processing.md)' is an overwhelming representation of the different biases and their various relationships. I think there are 180 or so here, and last time I saw a number reported in the literature it was around 260.

I complain about this in much more depth in that article I linked earlier, but fundamentally, if you’re trying to predict what biases people are going to engage in, you’re stuck panning through hundreds of the fuckers. As one economist puts it, imagine you’re trying to help granny plan her retirement: what biases is she going to suffer from?

Will they be loss averse? Present biased? Regret averse? Ambiguity averse? Overconfident? Will they neglect the base rate? Are they hungry? From a predictive point of view, you have a range of countervailing biases that you need to disentangle.

Not a good tool for predicting behaviour. And behavioural economists are starting to notice this too, most strikingly with the collapse of the whole ‘nudge’ thing.

But, a very good tool for explaining behaviour, as old mate back there points out:

From a diagnostic point of view, you have an explanation no matter what decision they make.

Now this is even worse news for prediction, because it means you can’t work out when you’re likely to be right or wrong. There’s a bias for every decision, but what are the chances each bias comes about?

But not everything is about prediction. Some things are about reflecting. And having a list of biases to apply to some failure of decision-making can certainly be illuminating.

More importantly, it conforms to exactly what I alluded to at the top of this article—the sociology of the interesting:

the most successful theories are those that subvert our weakly held beliefs. The hot-takes on things we don’t care very much about. If our strong beliefs are attacked, then we’re likely to resist the attack. If our existing beliefs are confirmed, we’re likely to do little more than nod and forget. But if the knowledge we don’t care about very much is revised, then it becomes interesting.

So not only can biases be useful in reflection, they can also be endlessly interesting too.

Bias isn’t always error

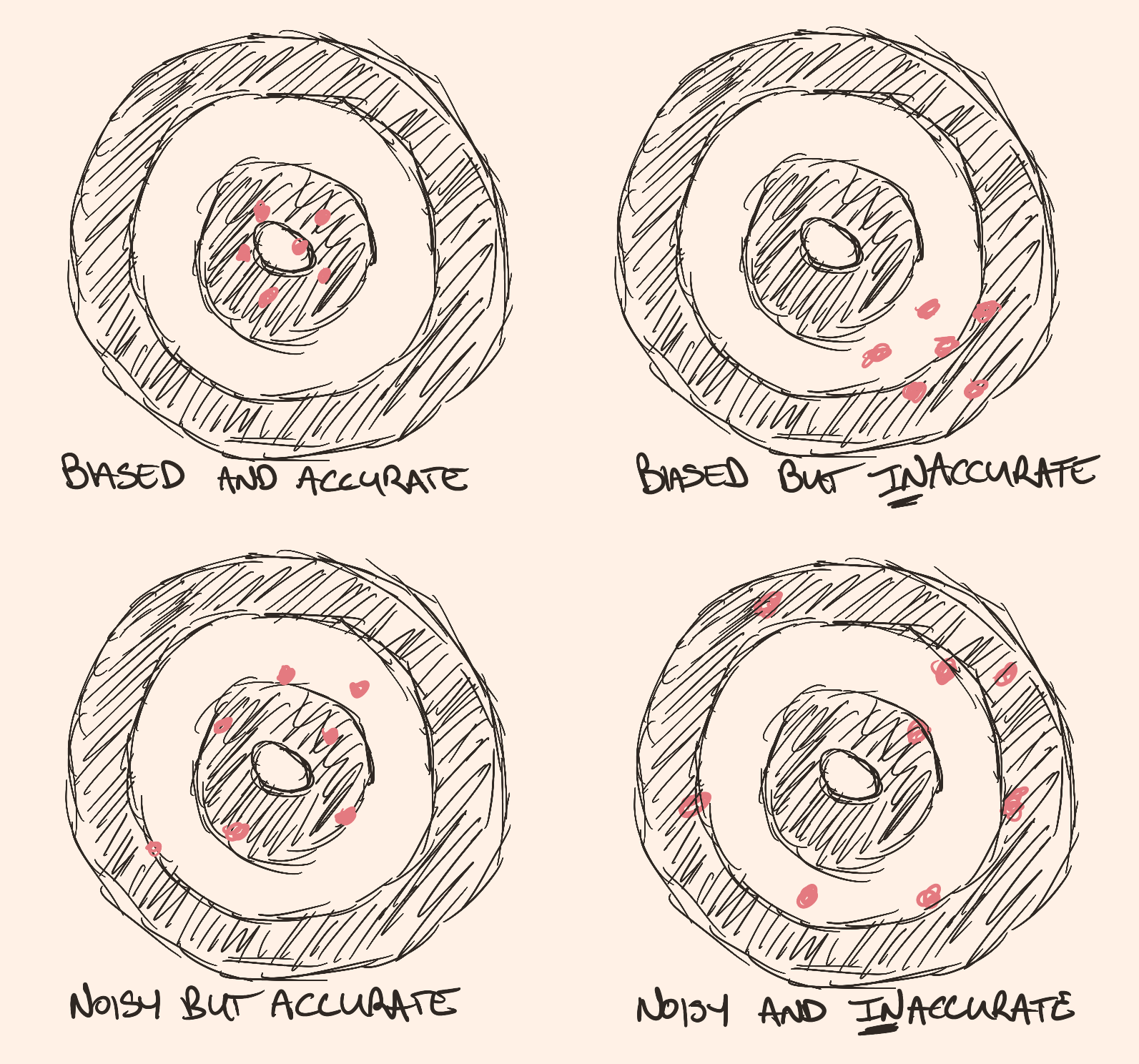

Behavioural economists only call errors in optimal or rational behaviour biases. But for everyone else, biases aren’t errors at all. ‘Bias’ is a statistical term, not an economic one. And when these people are talking about bias, they’re talking about the opposite of noise.

Bias is the opposite of noise, or variance. If you have a biased measure,

it's more precise. A noisy measure is more variable. But that's

orthogonal to accuracy---both biased and noisy measurements can be either

accurate or inaccurate. I should point out that though I picture noisy and

inaccurate here as a random scatter, it could equally be loosely clustered

off target.

Bias is the opposite of noise, or variance. If you have a biased measure,

it's more precise. A noisy measure is more variable. But that's

orthogonal to accuracy---both biased and noisy measurements can be either

accurate or inaccurate. I should point out that though I picture noisy and

inaccurate here as a random scatter, it could equally be loosely clustered

off target.

Above is my sketch of the difference that I write about in more detail elsewhere. But it’s not that complicated. If I wanted to count how many people are sleeping in my classroom, I could pick people at random and check. But what are the chances I catch someone who’s sleeping at the exact time they’re sleeping? It’s going to be noisy and inaccurate. So maybe I instead try to pay attention to everyone all at once. It’s going to be more accurate, but still noisy—particularly if my class is big—because I can’t pay attention perfectly to everyone all at once.

This is where I might decide to bias my search. I might choose to ignore the middle, and focus my search around the sides and the back of the class, where sleepy people feel less pressure to stay awake. I’m likely to catch many more sleepers now. My bias has made me more precise, by ignoring the noise.

Of course, my bias could lead me off-target too. If someone was thinking hard about all the profound stuff I was saying, they might have their eyes closed. Or, as happened one time during me delivering this exact bit, they might be simply looking down—not paying attention at all. And because I’m expecting sleepers, I might (and did) assume they’re asleep. Biased, but inaccurate.

Some more examples to drive the point home:

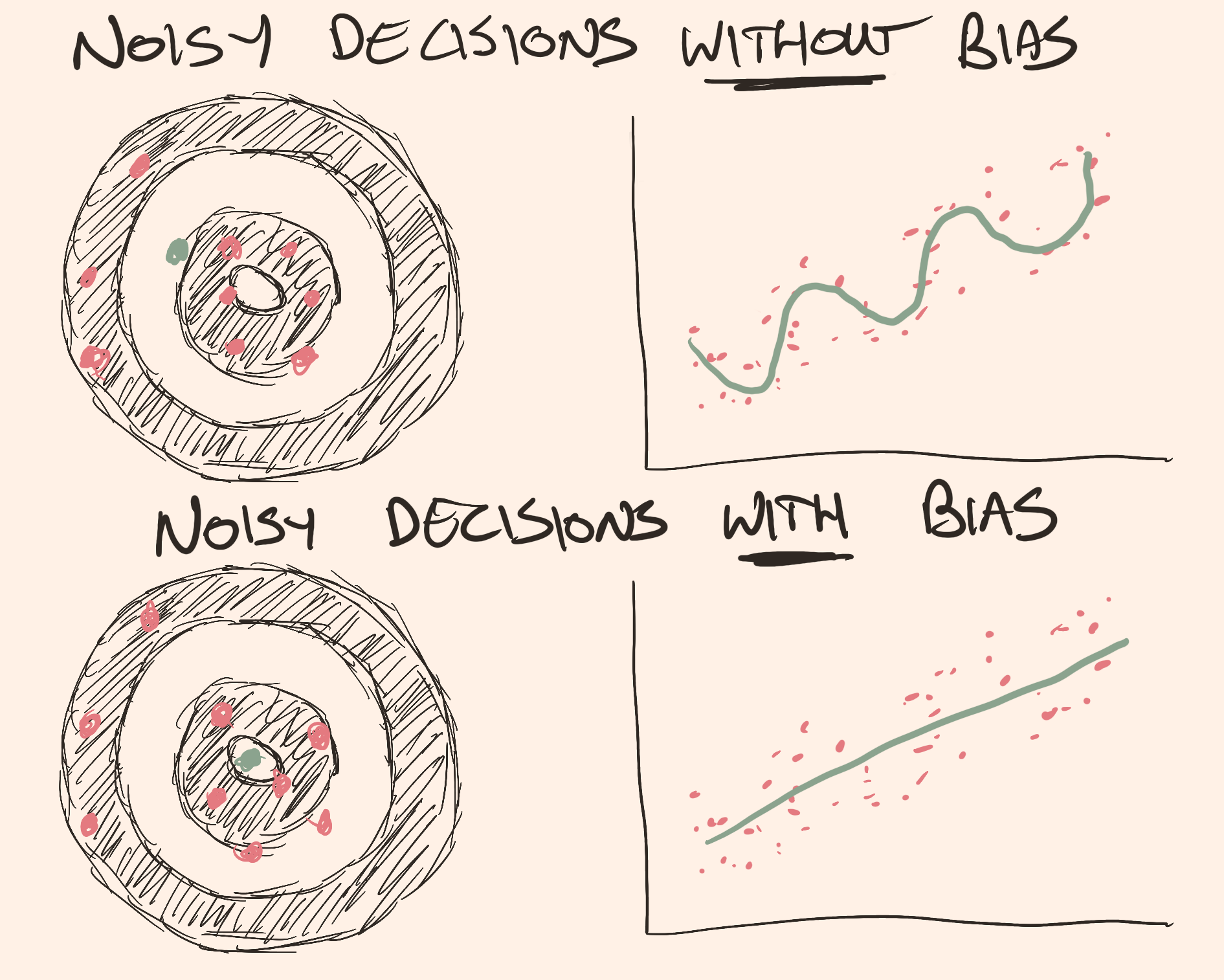

If we return to our dartboards, most of the results here are clustered

around the centre, but three are way off to the left. Without bias---the

expectation that my dart player is aiming for the centre---I might average

their results and decide they were aiming for the top left quadrant of the

dartboard. But with bias, I exclude these outliers, and I can tell

that most of the time they're aiming for the centre. Or, with my noisy

scatterplot here, without bias I might decide to pay attention to every

datapoint and I'd end up with this wiggly line that doesn't really help me

understand what's going on. With bias, I might decide that I don't

want wiggly lines---if I only draw a straight line, then this

makes much more sense of my data. It's a linear trend, not a wiggly one.

If we return to our dartboards, most of the results here are clustered

around the centre, but three are way off to the left. Without bias---the

expectation that my dart player is aiming for the centre---I might average

their results and decide they were aiming for the top left quadrant of the

dartboard. But with bias, I exclude these outliers, and I can tell

that most of the time they're aiming for the centre. Or, with my noisy

scatterplot here, without bias I might decide to pay attention to every

datapoint and I'd end up with this wiggly line that doesn't really help me

understand what's going on. With bias, I might decide that I don't

want wiggly lines---if I only draw a straight line, then this

makes much more sense of my data. It's a linear trend, not a wiggly one.

Again, there I’m using bias to help get some precision in all the noise. But of course, to use the examples from the picture, if my outliers aren’t outliers, then I’d be making a mistake to exclude them. Maybe the person was aiming for the upper left quadrant of the board. Or if there really was something that was causing my data to wiggle like that, biasing my results to prefer a straight line wouldn’t be the right thing to do.

This is called the bias-variance trade-off7. If you prefer bias over variance (i.e. noise), then you’ll get precision. But it’s fragile—if your expectations and assumptions are wrong, then your result is more likely to be wrong. If you prefer variance (i.e. noise), over bias, then you’re not going to be nearly as precise, but you’re less likely to be led astray by your expectations and your assumptions.

Outro

This might all seem academic to you, but it’s not academic to your brain. The bias-variance trade-off is one way to look at one of the most fundamental roles of your nervous system.

I write about this plenty, but the brain, and nervous system more broadly, has to map all the noise out there in the world to produce the right response. Not only that, but it has to coordinate all the noise inside your body to do it. Nerves innervating, muscles activating, hormones sloshing around in glands.

And most of the time, this is predictable. This is why I keep saying the brain maps the predictable structure of the world and your actions within it. By paying attention to the predictable stuff, and biasing your actions as a response, it can ignore all the irrelevant noise that might lead you to make an error. This frees it up to do more complicated processing when it doesn’t know what to expect—when it needs to pay more attention to the noise.

The brain isn’t a bias-reducing machine, like the behavioural economists would have it. It’s a bias-producing machine, because that’s a more efficient way of doing its job.

So we could sift through all 200+ biases that the economists care about, trying to work out which ones might happen. Or we could just look at how the brain manages the bias-variance trade-off, and what that means for behaviour. Seems obvious to me.

Examples to come in the next part(s?) of the series. The first one is on stress as perhaps the most fundamental of these in animals.

Assuming you’re not dyslexic or something. ↩

And indeed anyone I target in my atavism isn’t the answer article. ↩

Does soccer do jerseys? Or are they just called shirts? ↩

Don’t correct my stats, I don’t care. You get the point. ↩

A similar one is the representativeness heuristic. So, social stereotypes are usually pretty good. They speed up our ability to communicate and behave appropriately with one another. But we all know how this kind of thing can break down. Just because something is representative in some circumstances, doesn’t mean it applies all the time. ↩

Obviously, the complexity of the choice matters, as does what constitutes a ‘cost’ or ‘benefit’ and behavioural economists are silly about this too, but this is a different problem I won’t r ↩

See also accuracy vs precision. Also, I suppose, estimator bias although good fucking luck parsing that one. The only thing that really matters for you re:estimator bias are any bits that talk about how although an unbiased estimator would be ideal, its often practical to inject bias. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.