The most powerful way to get someone to like you, is to like them first

April 23, 2018

Excerpt: One of our most powerful urges is to be liked. Strange to find, then, that one of the most powerful influences on our likeability is whether others think we like them—‘reciprocal liking’.

Ideology

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

[P]ossibly, the most important determinant of how much we like a person is the extent to which we believe they like us.

Eliot Aronson, _[Symposium on Motivation][7]_

Plenty has been written on the means of social influence. I’m not just talking about the rise of the social influencer. It’s a fairly age old concern. In the 16th Century, Count Baldesar Castiglione published his famous The Book of the Courtier—a 300 page philosophical dialogue on how to “transform [oneself] into a beautiful spectacle for others to contemplate”, according to scholars on the subject. Today we have other resources…

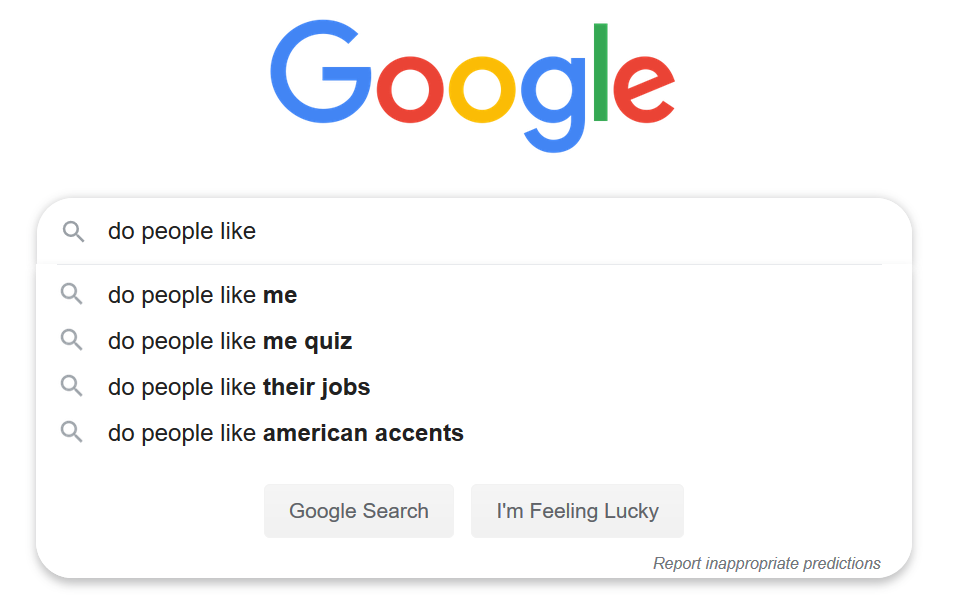

The results don't cheer you up. Google: 'do people like me'.

The results don't cheer you up. Google: 'do people like me'.

The impulse remains much the same (including, often, the Count’s mercenary attitude). It’s not surprising. Social isolation is thought to be one of the single most harmful factors to our wellbeing. But it’s more than that. To know you’re worthy of love is something that doesn’t just occupy our most fundamental models of human wellbeing, but our art, literature, and music.

Strange to find then that, in the midst of all these reflections, one of the most powerful influences on our likeability is whether others think we like them…

Reciprocal liking

Take for example this study: even when participants disagreed with a person on important issues, if that person maintained eye contact, leaned towards them and listened attentively, the participant would express great liking for them after the fact.

Or what about this, more recent one. One of the more well-researched phenomena in social psychology (and, frankly, one that needed the least research) is the fact that humans have a preference for attractive faces over unattractive ones. The more average and symmetrical a face is, the more attractive people will rate them (likely because it’s easier to cognitively process them). Introducing the idea that someone a participant expressed interest in reciprocated that interest completely disrupted the participants’ preferences for attractive faces. And this was just online. Combine those with the kinds of intimacy cues in the previous study and who knows how much more powerful the effect could be. Or rather, don’t. It’s been done.

Elliot Aronson and his colleagues paired people up in a few different ways, telling the participants privately that either: the other person liked them; didn’t like them; or alternatively they were told nothing at all. In the participants’ subsequent private ratings, those that ‘liked’ each other were friendlier, argued less and were more likely to report liking the person who ‘liked’ them first.

Why?

Hence, Elliot’s quote, summarising thirty years of research on the subject: “possibly the most important determinant of how much we like a person is the extent to which we believe they like us” (i.e. reciprocal liking). Strangely, just like the motivation to be liked, the power of this reciprocal effect is similarly related to self esteem. It’s been noted that those with higher self-esteem respond far more significantly to the effect than those with less. As Nathanial Branden put it, ‘self esteem creates… expectations about what is possible [for us]’. Perhaps it’s merely that the apparition of someone liking us is a more tangible opportunity than holding out hope that there might be a possibility someone else could like us another day. I guess that’s no suprise. We really are just animals, huh?

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.