Moral Blindspots

June 27, 2025

Excerpt: Most discussions about ethics centre on catastrophic scenarios. Situations where it’‘d be very difficult to avoid unethical behaviour. These scenarios aren’‘t really very interesting to me. What the average person probably wants to know is how to avoid the tamer moral lapses we encounter every day. What the average person wants to do is know how to avoid that single decision that might haunt them. So let’’s explore a more practical ethics. This is the second in the series—avoiding the moral blindspot.

Ideology

Most people think better ethical decision-making is just a matter of stopping to think before acting. But many moral judgements are intuitive, and then we rationalise them to ourselves. We have to train both intuition and reasoning, not rely on one to correct the other.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

If you already read the intro in another part, then you can skip to the content. See the whole series here.

I manage the ‘ethical leadership’ module at Sandhurst, among other things. The ethics of extreme violence is something that really bothers military leaders. Not just because they want to reassure themselves that they’re good people, even if they’re doing bad things. But also because people in the profession of arms are particularly prone to moral injury—the distress we experience from perpetrating, through action or inaction, acts which violate our moral beliefs and values. And also, frankly, because we keep doing atrocities, and this is very bad for PR.

When I arrived at Sandhurst, the lecture series on ethical leadership was very much focused on “how to not to do atrocities”. You can see me grappling with the lecture content in this series of articles. I wasn’t very impressed. It’s classic “look how easy it is to do atrocities” fare, with the standard misunderstanding of a handful of experiments from the 60’s and 70’s.

But it’s not easy to do atrocities. As I summarise in that series:

You have to train your authority figures to be cruel. You have to stop people from being able to leave or cease participating. You have to screen out dissenters. You have to do it over long periods of time and with an intensive level of engagement. And you have to constantly intervene to stop people’s better judgement getting in the way of the terrible goings on.

It’s actually really hard to be a catastrophic leader.

And many atrocities are exactly this. It’s not normal people slipping into terrible acts. It’s circumstances in which it would be very hard to avoid terrible acts.

These fatalistic kinds of events aren’t really that interesting to me, nor are they interesting to the average soldier, who’d prefer not to know how bad things can get. What the average person, and certainly the average soldier, wants to know is know how to avoid that single decision that might haunt them.

This is one of the difficult problems that a philosophy of ethics tries to deal with. But at Sandhurst, we don’t have time to do a philosophy of ethics course. It’s a 44 week course, mostly occupied by learning how to do warfighting. In that span, I get three lessons to help the officers do moral decision-making more effectively.

So we don’t want a philosophy of ethics. We want practical ethics that helps us very quickly get a sense of the moral terrain we’re facing. As such, in the process of making the module a bit more fit for purpose, I thought I may as well share it with you too.

Emotions come first

In the first part of this series, I talked about the moral terrain—a very simple primer into ethical philosophy. I did that because:

We need some background in ethics, of course, before we get into the practicalities, if only to understand why getting to practical ethics requires more than one article to explain.

The upshot of the article is that there are many different ways to think about what ethics is, and they don’t always align:

- You have principles of right and wrong, for example, like laws and obligations—this is called deontology and is one way of thinking about what’s right;

- You have the human desire to do the least harm and the most good—consequentialism and another way of thinking about things;

- You have the idea of a ‘good person’, and you might ask yourself what they would do—which is called virtue ethics;

- You have the fact that none of this matters when someone you care about needs help—an ethics of care; and

- You have your responsibilities to the community, which also aren’t always aligned to these other things.

And, as we did in the last article, it’s pretty easy to imagine a scenario where all of these things are happening at once:

If you’re walking down the street, late at night, and you witness a car-crash, you’re going to experience all of these lenses. You’ll look at the car, grey-haired figure waving weakly for help behind a cracked screen, petrol streaming from beneath, smoke curling from under the hood, cars whipping past in the cross-street, and suspect you should do something. But what? You know, in principle, you shouldn’t enter an accident scene unless you’re trained (deontic). You also know that that principle is probably designed to stop you messing the situation up more—hurting the elderly figure in the car, or causing more ruckus for the cars on the cross-street. But equally, wouldn’t it be so terrible if the elderly figure could be saved if you acted, and died because you didn’t (consequential)? So you’re paralysed. You say, “maybe I’m just being a scaredy-cat; I should be courageous” (virtuous), and so you start to move slowly toward the car, waving frantically for the traffic to stop. But as you get closer, you see through the cracked screen that the elderly figure is your granma. You start sprinting to the car—all thoughts of prudent traffic coordination lost (care). But, you catch yourself. You have a responsibility to those people out there (communitarian). You need to make sure they don’t have an accident, and so you start waving again—now time moving much faster towards granma.

You didn’t pick one ethical lens. You picked them all.

This is one problem of ethics. It’s messy. When trying to be ethical, people are buffeted by all sorts of impulses to act. Desires, intuitions, emotions. I write about it all the time, but I’ve never seen a convincing case for human decision-making and action that isn’t preceded by something like an emotion. Ethical actions are no different.

What do we do instead?

Models of ethical decision-making try to take this human messiness into account. As a prototypical example, the UK Home Office re-published theirs (pdf) in May of 2025. Step 1, for them, is to follow whatever existing decision-making process is currently in play, then follow it up with Step 2 during which you should ask:

Are there any ethical or unintended consequences in the proposed decision that concern you?

That leads you to Step 3—you need to follow that with a reflection on those things, and only then would you start Step 4—make your final decision. The Home Office doesn’t want it’s staff to just act without considering all this messiness. It wants its staff to think before acting.

But, as Jack Kem, once a Professor at the US Army Command and General Staff College, pointed out in the early 2000’s, these kinds of models don’t take into account the complexity that drives our impulses. You can’t just ask ‘are we being ethical’, because as we described earlier, there are many different kinds of ethicality jockeying for our attention.

It’s not enough to acknowledge that our decision-making is messy, and build in space to un-messify it. You also need to build in some structure around why it’s messy. Kem, paraphrasing ethicist Rushworth Kidder, notes:

Ethical dilemmas essentially consist of competing virtues that we consider important, but which we cannot simultaneously honor … There are four common “right versus right” dilemmas … truth versus loyalty, individual versus community, short term versus long term, and justice versus mercy.

So, Kem tries to structure this reflective step through an ‘ethical triangle’ that might help us untangle the mess:1

The third step is to examine the two most apparent alternative courses of action through the lens of the three ethical systems. The most methodical means to do that is to first look through principles-based ethics, then consequences-based ethics, and finally through virtues- based ethics.

Kem's 'Ethical Triangle'---consider principles, consequences, and virtues, to help decide which 'right' is the most important right.

Or, Dennis Vincent, once head of the Behavioural Sciences Department at the military academy at Sandhurst in the UK, has his S-CALM model, which also tries to help people navigate the competing demands of ethical decisions. Vincent was less interested in the differing ethical lenses, and more interested in the messiness of our human behavioural responses. He proposed a handful of messy human predispositions that seemed most associated with unethical military behaviour, and a series of questions that might help you think through the appropriate response.

Whoever’s model it is, the process is to stop before deciding and consider the moral terrain first. Only then is it time to move toward a decision.

And this approach is fatally flawed.

The fatal flaw

One of the reasons Vincent wasn’t convinced that merely looking through ethical lenses was sufficient was the influence of the situation on human behaviour. It’s all well and good to peer through ethical lenses, but one also must be aware of the ways in which situations—particularly stressful situations—create chains of

unethical actions, that they would not normally do if they were in a non-stressful situation and acting rationally.

Then he makes the point that:

This chain tends to be dominated by System 1, intuitive, fast thinking.

Vincent is referring to Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow in which Kahneman:

describes two broad categories of human thought:

- System one is fast, unconscious, automatic, and intuitive.

- System two is slow, conscious, effortful, and deliberative.

So when you drive a familiar route and find yourself at the end with no memory of the drive, that’s System one—fast, automatic, unconscious. Or when you tell me what 1+1 is. Or read these words.

When you’re driving to a new place, and you need to work out how long it’ll take and which route will have less traffic, that’s System two—deliberative, effortful, and slower. Or calculating 26*49. Or working out what these words mean, rather than just reading them.

Kahneman’s book popularised dual process models of cognition—models which bucket thinking into two kinds, a fast intuitive kind and a slower deliberative kind. But Kahneman wasn’t so much interested in the difference between fast and slow thinking. He was interested in the kinds of errors that fast thinking sometimes produces. He, and the behavioural economists he inspired, called these errors biases.

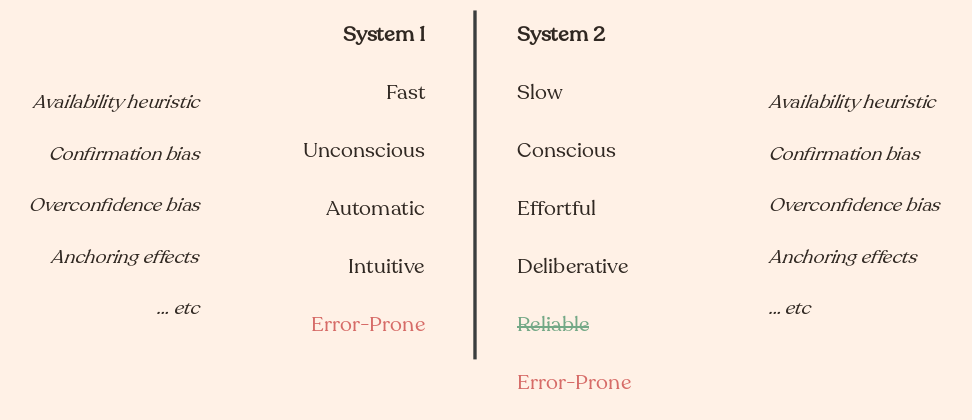

The book has led to a common misunderstanding of the concept of bias—the idea that System 1, or fast thinking, is error-prone, and System 2, or slow thinking, is more reliable. But that isn’t the case. System 1 and System 2 are both prone to errors.

The correct interpretation of System 1 and System 2. Both suffer biases. Both are error prone. System 2, or 'fast' thinking, isn't more reliable than System 1.

The correct interpretation of System 1 and System 2. Both suffer biases. Both are error prone. System 2, or 'fast' thinking, isn't more reliable than System 1.

Vincent makes the same mistake with his model. Remember Vincent’s quote from earlier—situational influencers:

in turn changes their behaviour and leads them to do unethical actions, that they would not normally do if they were in a non-stressful situation and acting rationally. This chain tends to be dominated by System 1, intuitive, fast thinking.

Vincent later provides the solution:

The leader also needs to be aware of the behaviours that their team are susceptible to before they get into stressful situations. Once they are in the situation, they need to use their System 2 thinking whenever there is time to do so, to recognise how the situation may be driving their thought processes.

System 1 is bad, so we need to use more System 2 thinking.

I use Dennis Vincent here, partially because I’m most familiar with his model, but also because this misunderstanding underlies almost all ethical decision-making models. As we covered in the last section, they all want you to stop and think before acting. Less System 1, more System 2.2

And in the case of ethical leadership, this is precisely the wrong approach.

Popularised by Jonathan Haidt, but stretching back to at least David Hume,3 an extremely rich body of literature demonstrates that, in the case of moral judgement, System 1 very frequently drives System 2 rather than getting corrected by it.

The main evidence for this is what’s become known as moral dumbfounding. For example. Imagine a beautiful family, with a beautiful family dog, in front of a beautiful family home. Then, perhaps in some tragic car accident, the dog is killed. The beautiful family takes the dog inside, seasons it, cooks it, and serves it for dinner.

In a predominantly anglo culture, most people will have an intuitive sense that this is wrong, but if you ask them about it, they will probably struggle to say why. Something about desecration, family, love, maybe. But a clear reason won’t be forefront—it only emerges later.4 And often, across different questions, the moral reasons that emerge later will change. You ask them why it’s wrong and they say “it’s disrespectful to the dog”. But the dog is dead, and was cherished in life, so that doesn’t make sense. So they might swap to “it’s not safe to eat roadkill”, but if it was pointed out to them that the dog wasn’t really hit badly by the car, and it was well-cooked—perfectly safe, they’d change again. Maybe “it sets a bad example for the children”, but an example of what, exactly? We’ve just pointed out that there wasn’t anything obviously wrong. Eventually, they might give up—it’s just wrong! They are morally dumbfounded.

We must assume that there are many times, when our rationalisations aren’t questioned, that our reason ends up feeding our intuitions and not the other way around. This is what these social intuitists—as they’re called—would have us believe. That many moral judgements are made fast first, and then they drive our slower thinking processes to justify them.

It’s motivated reasoning at its finest.

What we should do instead

Ethical decision-making models want you to think first, and act afterwards. But some substantial proportion of our moral judgements happen before we think, and then determine what we think about. It’s not always a case of System 2 correcting System 1. It’s a case of System 1 driving System 2. In this kind of relationship, trying to rely on System 2 is only going to reinforce our behaviour—ethical or no. It’s a recipe for moral blindspots.

Instead of viewing moral decision making, particularly under stress, as some kind of internal civil war, we need to be looking at the two of them holistically. If you’re spending time trying to train yourself to think more ethically—consider behaviours and situations, or different ethical lenses—you should be spending the same amount of time drilling your moral intuitions.

You’re not going to improve shitty actions with ethical thinking, you’ve got to learn both together. That’s the key to a practical ethics.

The next article, Practical Ethics, finally gets us there.

This appears to be an advance on Kidder’s own ethical triangle, but Kem, like most military ethicists, preferred virtue ethics to what Kidder calls ‘care-based thinking’—a reference to the golder rule, not a feminist ethic of care—the idea you should do unto others as others should do unto you. ↩

I should point out that most people will talk about Kohlberg’s model of moral reasoning at this point. But I’ll use System 1 and System 2, because I suspect most people aren’t basing their intuition that they should ‘stop and think’ on any particular model. They’re just basing it on the same kind of intuition that made Kahneman mistrust System 1. ↩

You’re looking for the bit that reads “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them”. But you find people discovering this over and over again. Other examples I’ve come across include include Nietzche’s Geneology of Morality (pdf), or Sperber and Mercier’s Enigma of Reason, or a very compelling recent article that reckons all ‘biases’ are just variations on confirmation bias. ↩

This all assumes they aren’t trying to be clever, or are poorly socialised, and say things like “there’s nothing wrong with eating dogs”. The point of this isn’t to catch cultural heathens, but point out that we have moral heuristics. This is probably why the authors of moral dumbfounding usually use non-reproductive incest as the example. It’s harder to pretend it doesn’t bother you. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.