Beyond System 1 and System 2

June 13, 2025

Excerpt: Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2—our fast, intuitive autopilot versus slow, deliberative override—have become a shorthand for human thought. But thinkers from Evans and Sloman to Stanovich and Minsky remind us that cognition isn’t just a two-lane road. It’s a bustling coalition of specialised processes—heuristics, conflict-detectors, symbolic reasoners—all running in parallel or in nested hierarchies. Fast versus slow will do as a starting point, but the real story lies in the many flavours and layers of mind at work behind the scenes.

Ideology

System 1 vs System 2 is a useful shorthand, but our minds aren’t two-speed engines—they’re multi-process coalitions of specialised agents working in parallel and in series.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

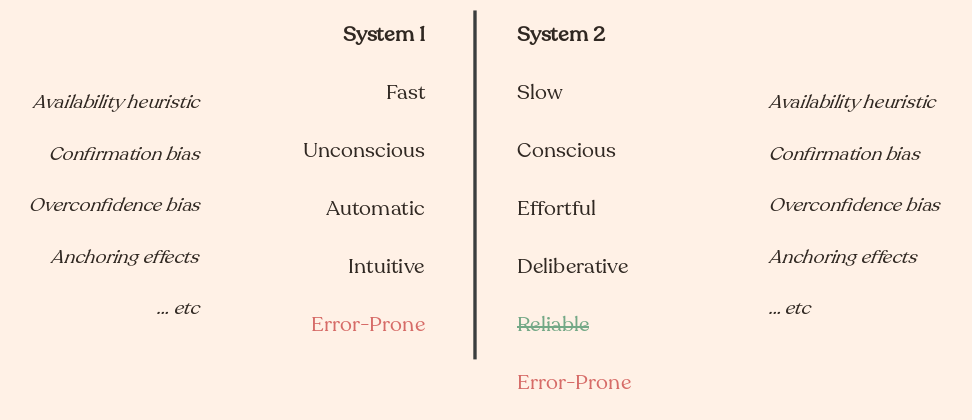

In 2011, Daniel Kahneman published Thinking Fast and Slow—one of the most popular non-fiction books of the 2010’s. In it, he describes two broad categories of human thought:

- System one is fast, unconscious, automatic, and intuitive.

- System two is slow, conscious, effortful, and deliberative.

So when you drive a familiar route and find yourself at the end with no memory of the drive, that’s System one—fast, automatic, unconscious. Or when you tell me what 1+1 is. Or read these words.1

When you’re driving to a new place, and you need to work out how long it’ll take and which route will have less traffic, that’s System two—deliberative, effortful, and slower. Or calculating 26*49. Or working out what these words mean, rather than just reading them.

Fast vs slow thinking, Kahneman called them, and it’s a pretty neat dichotomy if you’re going to put all human thinking in two buckets.

So neat, in fact, that he’s hardly the first to have had the idea. Kahneman’s book is just one example of what are broadly known as dual process theories. You might know it under different names:

Hot and cold thinking, fast and slow thinking, passion and rationality, emotion and reason.

See, there are a bunch of these dating back forever, for two reasons. The first is because the idea is so intuitive that lots of people have it. As I say elsewhere:

Plato described emotion and reason as the horses that pull us in two directions. The biblical prophet Isaiah encouraged us to come together and reason, rather than act without thinking.

I’m referring there to Plato’s allegory of the two-horsed chariot in the Phaedrus,2 and the first chapter of Isaiah, which is, honestly, a bit of a reach, but you could trade it for Galatians 5:16 or James 1:19 or Romans 7:18 and get the same idea. Spinoza is another famous philosopher that has a very dual-process-ey approach to emotion. William James, who honestly seems to have got around to every concept in modern psychology, has a bit on the difference between associative and reasoned thought. And so on, and so on. Lots of people have a thing on this. You’ve probably noticed things like this. There are thinky ways of doing things and unthinky ways of doing them.

Then there’s the second reason dual-process theories are so ever-present in our culture. A reason that makes them more interesting than their obviousness would seem to imply. The second reason there are so many of these theories is because people use them to explore different aspects of behaviour. Plato was interested in the most intuitive, and sadly overestimated form of the idea—that we must use ration to wrangle our passions. The biblical quotes are interested in how we can appeal to a higher power for help in the wrangling. Spinoza is interested in the power of awareness in transforming our emotional experience. James was interested in the power of associative thought.

Each approach to dual-process theories has its own flavour to it. That’s why people keep coming back. And this article will explore some of those flavours, because ‘thinking fast and slow’ isn’t the only flavour worth paying attention to.

The popular view

I have an entire article about this, so I won’t spend much time here, but Kahneman was interested in the kinds of quirky errors our fast thinking produces that our slow thinking fails to correct. He wants us to see our fast thinking as a collection of rapid rules-of-thumb—heuristics—that determine most of our behaviour because they’re cheap and easy. Our slow thinking is more expensive, and is used less often. Sometimes to endorse our heuristics, but usually to modify or override them when they’re wrong.

Many people have taken that to mean that fast thinking is error-prone, and we should rely more on our slower ‘more reliable’ thinking to overcome these errors, but Kahneman never actually said that. He reckons both are error-prone, he’s just particularly suspicious of fast thinking:

The lax interpretation of System 1 and System 2 places a lot of blame for poor decisions on System 1. It's easy to assume that fast thinking is error-prone. This isn't what anyone who knows what they're talking about thinks though. Both 'Systems' suffer biases, and both are error prone. System 2, or 'fast' thinking, isn't more reliable than System 1, and for these biases, is even more prone to error.

So the more correct and probably the most common view thanks to Danny Kahneman is that fast thinking is our cheap, default way of thinking, and expensive slow thinking sometimes intervenes.

The competitors

Kahneman’s view isn’t the only view, though. Lots of people agree on a split between fast and slow thinking, but not everyone is convinced that it’s this kind of interventionist model—that the main thing slow thinking does is intervene on fast thinking. Other people like to use the theory to highlight other apparent features of the two systems.

The inspiration for Kahneman’s book was Jonathan Evans’ heuristic-analytic model. Evans introduced the word ‘heuristic’—he thought we have the default, cheap, fast processing (heuristic) and the interventionist, costly, slow processing (analytic). But Evans wasn’t a behavioural economist, so he wasn’t so interested in the times where our fast thinking made errors—where they deviated from the ‘rational’ decision. He was looking at how the analytic system wouldn’t really pay close attention unless it detected a conflict. So, to use the example Kahneman also picked up for his book, if I asked you:

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total.

The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

Your heuristic system is going to immediately suspect that the answer it 10 cents. But, if you’ve had your coffee today, you might also have the intuition that—wait a second—if the ball is 10 cents and the bat is $1.00 more than the ball, then we’re already over $1.10 when you add up the total. So, now, your analytic system starts to sluggishly move over the problem to sort out the conflict. Evans wasn’t interested in the times the analytic system doesn’t wake up like Kahneman was, he was just interested to see that we’re on some kind of autopilot most of the time, unless we experience some conflict or violation of our expectations.

Steven Sloman was a little worried about this interventionist account. He thought that it wasn’t so much that our slow thinking only gets “switched on” occasionally. He reckoned that both systems happened in parallel.3 The slow thinking isn’t just waiting to step in when there’s a conflict, it’s doing different work at the same time as the fast thinking, and sometimes they end up competing. So, he looks at, for example, the Müller-Lyer illusion:

Although the lines are all the

same size, the line-segments between the arrow heads look smaller to most

people than the ones between the inward-pointing fins.

Although the lines are all the

same size, the line-segments between the arrow heads look smaller to most

people than the ones between the inward-pointing fins. Sloman realised that the illusion:

suggests that perception and knowledge derive from distinct systems. Perception provides one answer; the horizontal lines are of unequal size, although knowledge (or a ruler) provides quite a different one—they are equal. The knowledge that the two lines are of equal size does little to affect the perception that they are not. The conclusion that two independent systems are at work depends critically on the fact that the perception and the knowledge are maintained simultaneously. Even when I tell myself that the lines are of equal length, I see lines of different lengths.

Both our fast thinking and our slow thinking are co-existing. In this, he follows on from William James, who noticed more than 100 years ago that our associative-perceptual systems seem to be distinct from our rule-based reasoning. Sloman would tell you that our associative system differs from the rule-based system in that the rule-based system is operating on things we hold in our minds, rather than things that pass through our eyes and ears, and they don’t have to have any relationship to each other.4

Then there’s models like Keith Stanovich’s tri-process theory (pdf). Stanovich, and those like him,5 reckon that the idea of two processes are too few. There’s the automatic fast thinking, yes, but the reflective slow thinking is actually two-fold—a goal-tracking sort of system and a separate suite of tools the goal-tracker uses to make sure you’re on track.6 That our intelligence is different somehow from the thing that determines what that intelligence should be applied to. And that both of those things are distinct from the automatic heuristics of our fast thinking.

Which leads us to the natural end-point of trying to elaborate on the architecture of the mind. It’s quite natural to say that there seem like two categories of thinking—fast thinking and slow thinking. But you’ve probably already worked out that—like the biblical scholars and the philosophers long ago, or like the academics I’ve wandered through here—you could slice up these categories of thinking in a bunch of different ways. In fact, you sometimes have to. For example, if you were to spend a long time trying to work out whether to move to a new city for a better job, you’d have your automatic thoughts:

- Something emotional is getting excited about the better salary;

- Something about availability is calling up all the instagram reels of mates who’ve moved and loved it;

- Something risk-averse is worried about the housing costs;

and so on. As you think more about it, you might decide to plug things into a spreadsheet to work out how much the move will actually cost—correct your ‘biases’ from those automatic thoughts. But how do you tell these things apart? You could have:

- Thinking about expense items coloured by confirmation bias, making more expensive or cheaper options more obvious to you depending on whether you’re more excited or more risk averse;

- Your emotional thingo is still getting excited about weekend hikes in the mountains, making you reflect more on that and less on the social isolation of the area;

- And some kind of fluency heuristic is making simpler options sound truer than more complicated ones, even though you’re working diligently to compare them.

Is this fast or slow thinking? You couldn’t really say.

Societies of Mind

No one serious really thinks there are only two or three kinds of thinking. Obviously they’re just ways to bracket some unknown number of possibly distinct cognitive processes.

You’ve got a bunch of fast sub-systems. Edge- and contrast-detectors in the visual processing pathway, face-recognition circuits, a cheating-detector, some kind of goodness-or-badness register, and so on. These things happen automatically, often in parallel, and almost always before you have any kind of sense that you’re “thinking”.

You’ve also got a bunch of slower sub-systems. Some kind of symbol manipulator that helps you with math and logic. Some kind of narrative builder that helps you rope all this chaos into some kind of meaning. Goal-trackers and controlly-bits that make sure things aren’t getting out of hand. Some kind of ‘am-I-sure’ mechanism that helps you search for and choose between alternatives. And so on.

If you just glance at them, they look like two layers—System 1 and System 2. But obviously there are clusters within clusters of types of thinking.

And so we have people like Carruthers with his idea of massive modularity or Minsky with his Society of Mind. Cognition is a coalition (or coalitions) of little mental processes all jockeying for space, not a hierarchy with a couple of layers.

Outro

You already knew all this, but it helps to put the words around it. It also probably helps explain why parts work is so successful as a model of self-help and coaching. Your mind really does seem to be made up of parts. Tiny agents who come together to make temporary cognitive coalitions in service of some goal or other, greater or lesser, long-sighted or short-sighted. It’s all very messy. So, System 1 and System 2—fast and slow thinking—why not. It’ll do.

Assuming you’re not dyslexic or something. ↩

And I am glossing over the fact that it’s more like the charioteer and the white horse together comprise our notion of reason. This isn’t an article, in the main, about ‘tri-process models’. But I do talk about Stanovich’s tri-process model. And there, you can make Plato’s allegory work better. A better dual-process split might be Epictetus on the difference between phantasia (impression) and prohairesis (rational assent, or something like that). But you get it. Two horses is cuter. ↩

See also the second section of his recent review paper ↩

This is actually the old connectionist-vs-symbolic cognition debate. The abstract for Pinkers 30 year old book actually gives a lot of context in a short paragraph for this. Sloman is saying that he reckons they both exist, essentially, where a lot of contemporaries were gunning for one over the other. Connectionism sort of won this, but I think if you read some of the cognitive neuroethology stuff (e.g. Gallistel), you will see why symbolic processing is probably a thing. Certainly it seems like AI is demonstrating that, despite the early enthusiasm, connectionism is not quite enough. ↩

He calls this the algorithmic mind, but I haven’t read enough of him for this to feel intuitive to me. It’s something like fluid intelligence—horsepower or processing speed or something. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.