Stress and Creativity

March 28, 2025

Excerpt: Bias is just you using your expectations and assumptions to ignore the noise, and see the picture more clearly. The trade-off is that, sometimes, the noise is useful or your expectations are off. The human stress response is perhaps the most fundamental example of this in behaviour, and a very valuable tool.

Stress promotes bias—stereotypical thinking and behaving. Less stress promotes cognitive flexibility—an openness to new ways of thinking and behaving. Neither is better than the other. It’s about the situation you deploy them in.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

In the first part of this series, I tried to convince you that bias was a good thing, then I promised that I’d show you how that plays out in human behaviour. So let me recap the main idea to save you reading that first article again, and then I’ll get into showing you how. In this article it’ll be by showing you how stress promotes performance through bias.

Find the rest of the series collected here.

If you already read the first part, then you can skip to the showing

Recap

Behavioural economists have the world terrified of biases. Groupthink, confirmation bias, negativity bias, optimism bias, etc, etc. You’ve probably read about at least one of them. You see, they:

work off the assumption that humans are ‘rational actors’. They call it the ‘rational-actor model’. The idea, more-or-less, is that if you give a human a decision to make, they will decide by optimising for their preferences, weighing up the costs and benefits. You do stuff that does the most good for you, and the least bad. On this model, errors should only happen when you don’t have the right information to make the ‘rational’ decision. … ‘biases’ … are times when we deviate from this model. When we make choices that are not optimised to our preferences, maximising benefit and minimising cost, despite having accurate information.

But statisticians don’t see bias this way, and the brain is much closer to a statistician than an economist. For them, bias is one half of a trade-off.

Bias is the opposite of noise, or variance. If you have a biased measure, it’s more precise. A noisy measure is more variable. But that’s orthogonal to accuracy—both biased and noisy measurements can be either accurate or inaccurate.

The idea is that, sometimes, you want to use your expectations and assumptions to ignore the noise, and see the picture more clearly. The trade-off is that, sometimes, the noise is useful or your expectations are off.

This is, more-or-less, what the brain does:

the brain, and nervous system more broadly, has to map all the noise out there in the world to produce the right response. Not only that, but it has to coordinate all the noise inside your body to do it. Nerves innervating, muscles activating, hormones sloshing around in glands.

And most of the time, this is predictable … the brain maps the predictable structure of the world and your actions within it. By paying attention to the predictable stuff, and biasing your actions as a response, it can ignore all the irrelevant noise that might lead you to make an error. This frees it up to do more complicated processing when it doesn’t know what to expect—when it needs to pay more attention to the noise.

So, that’s the first article. Let’s look at an example.

Stress is about bias vs noise

I want to talk about the Yerkes-Dodson law again. In that article, I talk about how, contrary to popular belief, stress is perhaps the most important biological technology we have. Stress, or the sympathetic nervous response, is the thing that recruits all the cognitive and physical resources we need to tackle the challenges we face:

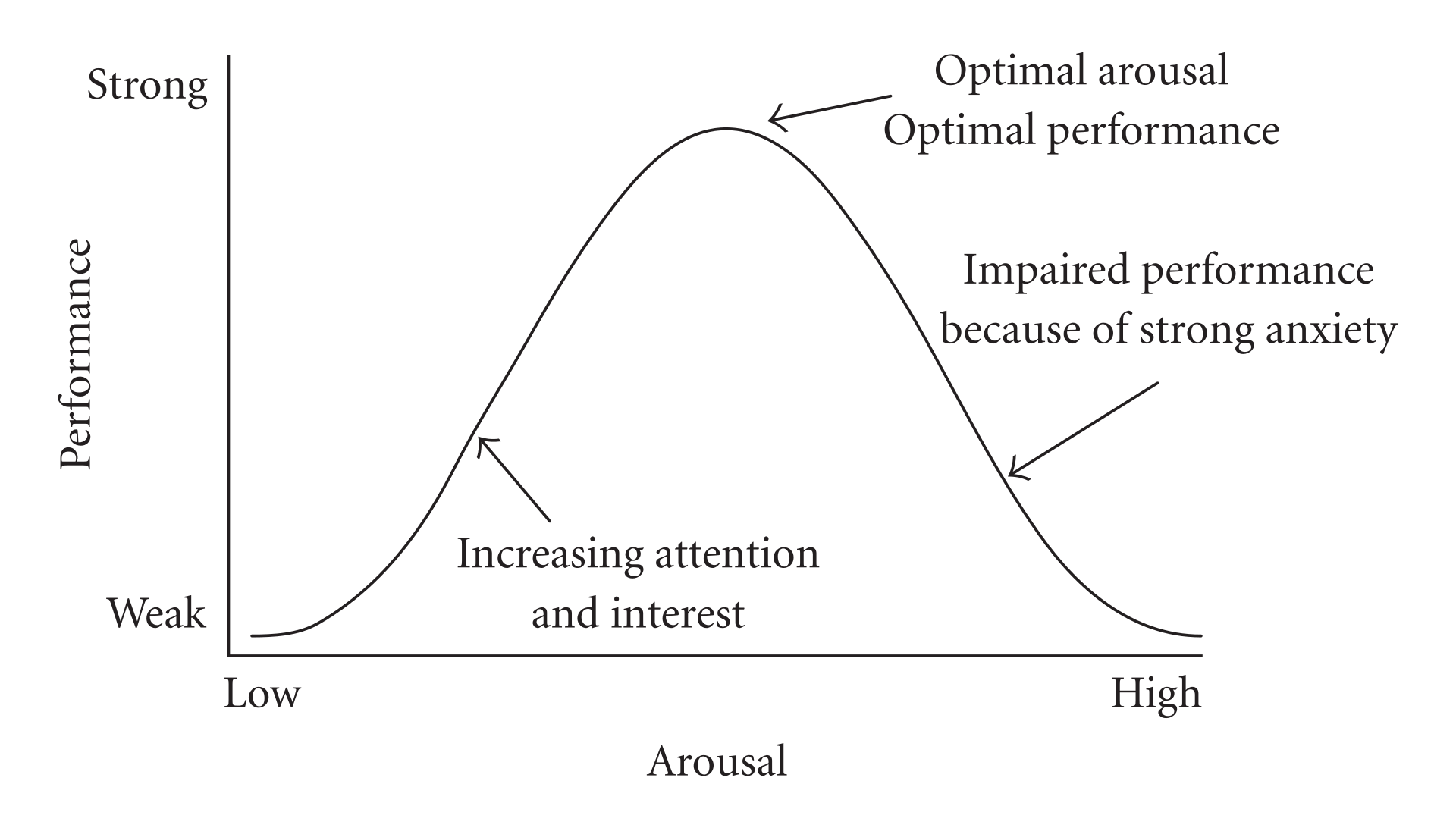

As arousal increases, so does performance. To a point. Eventually, as arousal

continues to increase, performance starts to decrease. Wikipedia.

As arousal increases, so does performance. To a point. Eventually, as arousal

continues to increase, performance starts to decrease. Wikipedia.

Too little stress, and we aren’t very motivated to act. You’re not idly playing with spreadsheets in your spare time. A bit more stress—maybe the spreadsheet is due in a few days—and the stress is recruiting attention and interest and you’re starting to fix the thing. Enough stress, and now it’s the only thing you’re concentrating on—optimal stress, optimal performance. But a bit more stress—maybe it’s due tomorrow and you’ve realised some important macro isn’t working—and now you’re freaking out; the adrenaline is making your hands shake; maybe a bit of brain fog, etc. You’ve moved from eustress, good stress, to distress. Your performance is going to suffer.

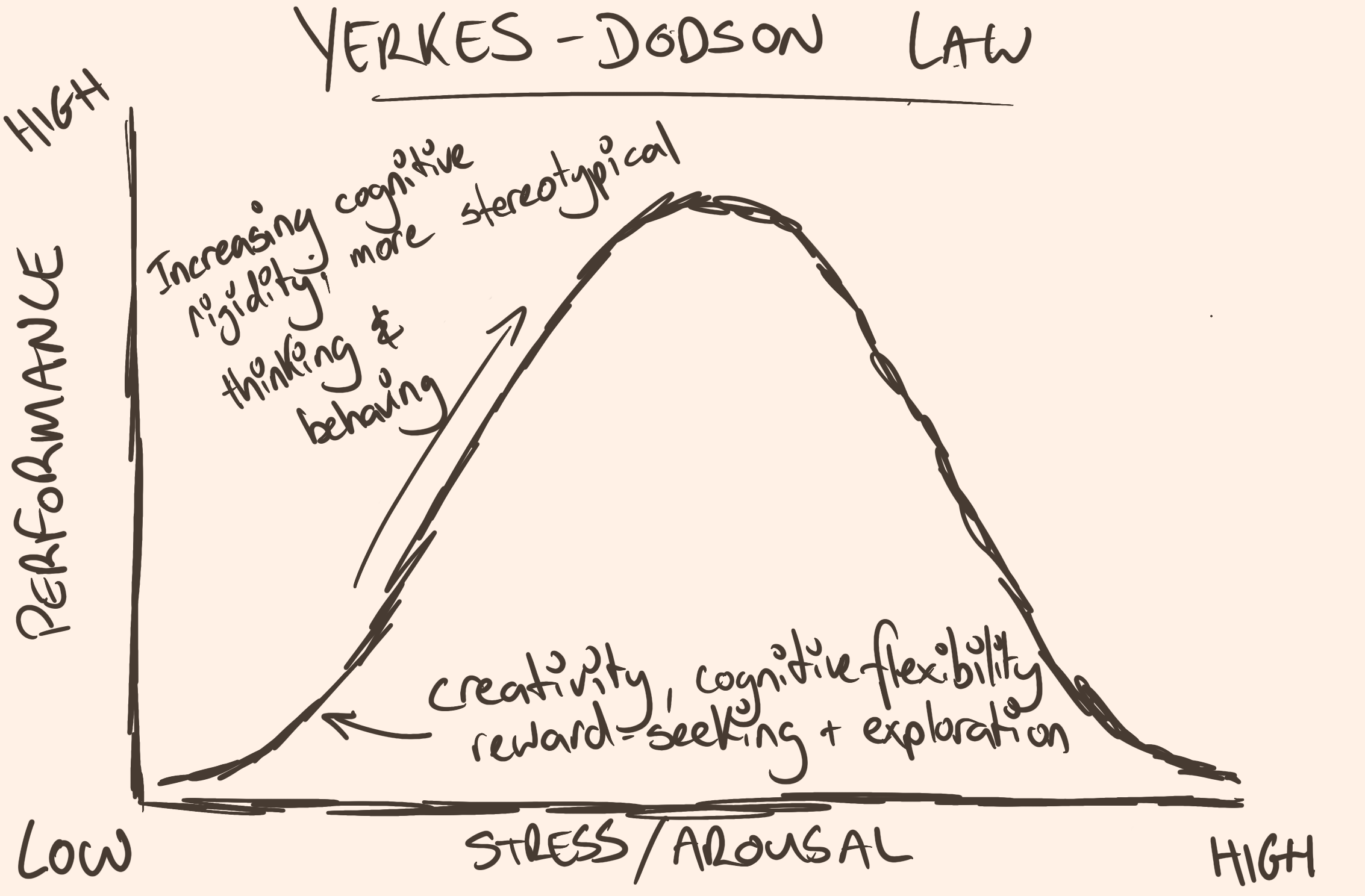

But as I touch on in my last article on bias, that’s only one of the stories the Yerkes-Dodson law teaches us. It’s also a very handy demonstration of the bias-noise trade-off:

Low stress is associated with cognitive flexibility, exploration behaviour, and

reward-seeking. Creativity, in short. As stress goes up, we become more

cognitively rigid; engaging in more stereotypical patterns of thinking and

behaving.

Low stress is associated with cognitive flexibility, exploration behaviour, and

reward-seeking. Creativity, in short. As stress goes up, we become more

cognitively rigid; engaging in more stereotypical patterns of thinking and

behaving.

One of the reasons performance goes up with stress is because it starts making us behave in more familiar, practiced ways. We become more cognitively rigid, and engage in tasks in more stereotypical ways. If we know how to do something, or have been trained to do it a certain way, then this is going to be a pretty substantial improvement to getting the task done. You’re more stressed, so you’re not going to be spending time experimenting with new macros that might make the spreadsheet better, but equally might fuck everything up. You’re going to use what you know to get the job done.

This is bias. You’re ignoring noise, and leaning into a certain way of doing things that you expect will produce better results. For most things, this is going to be very good. But it’s a trade off. If you don’t know how the thing should be done, doing it in a more stereotypical way isn’t necessarily going to improve the situation.

Instead, when things are a little more uncertain, you probably want a more low-stress environment. More cognitive flexibility; creativity. You want to be open to new ways of doing things. You want to be open to noise.

More stress makes us more likely to do things how they should be done, and less stress makes us more likely to consider how things could be done. A classic bias-variance trade-off, and maybe the most fundamental to animal behaviour.1

Caveats and outro

This 100-odd-year-old stress curve of Yerkes’ and Dodson’s obviously hides a lot of detail. I only use it because it’s a much better simplification of how stress works than the old amygdala shuts down your thinky-bits narrative.

So I’m defining performance very loosely here. Like, if we’re talking about performance under conditions of uncertainty, then maybe this curve isn’t going to be quite the right thing, because you’re restricted to that bottom left corner. You’d probably be wanting to think more about resilience to stress then, or other models around how the brain generates creativity

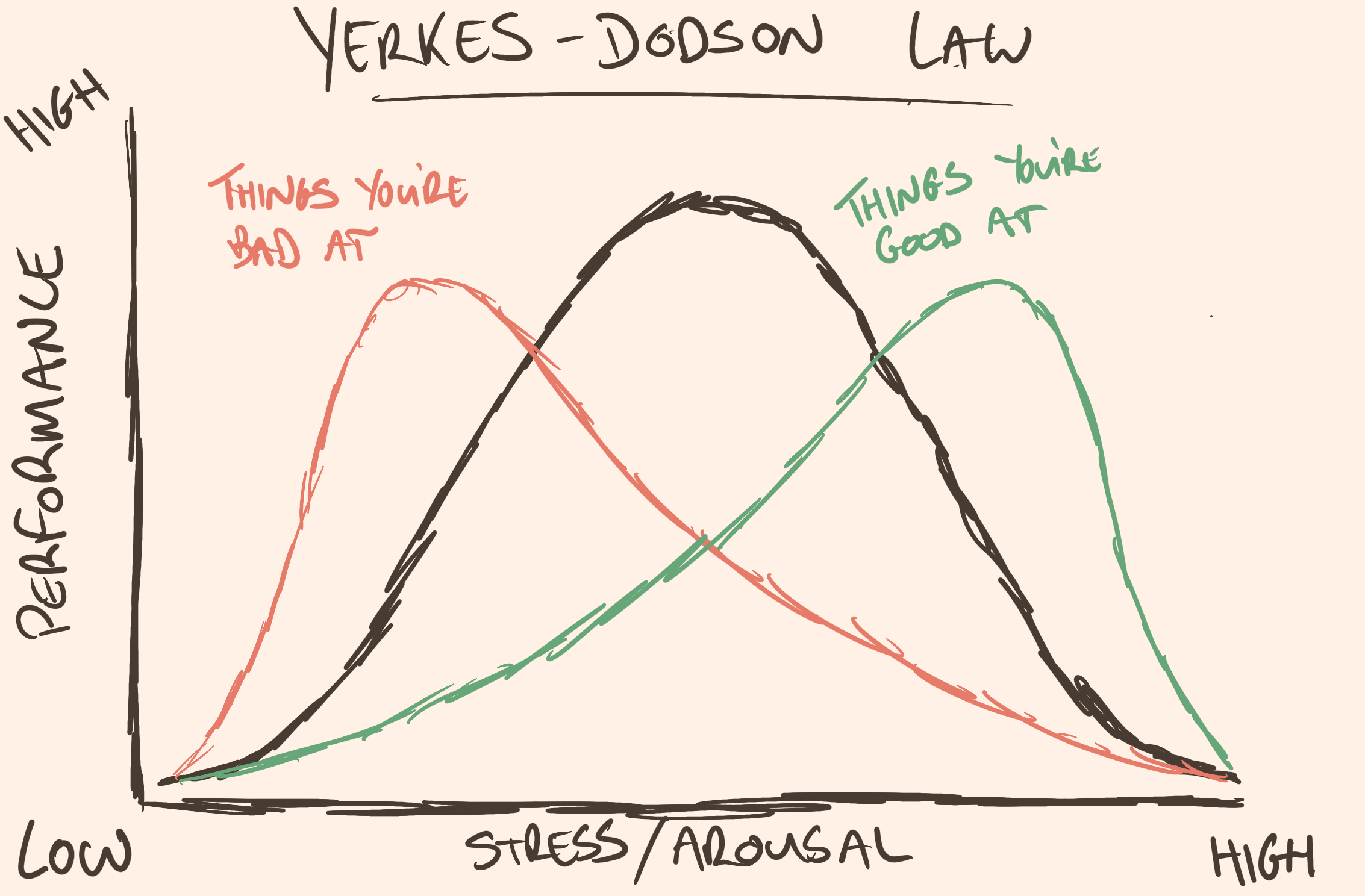

Or, the curve won’t look the same for every person, or even every task. You probably find that you’re more resilient to stress when you’re good at something, so your performance curve will have a much longer tail on the left, and a shorter tail on the right. The inverse is probably true for things you’re bad at.

Tasks we're less well trained at are going to have more room for bad stress and

less room for good stress. The opposite is true for tasks we know we can do

well.

Tasks we're less well trained at are going to have more room for bad stress and

less room for good stress. The opposite is true for tasks we know we can do

well.

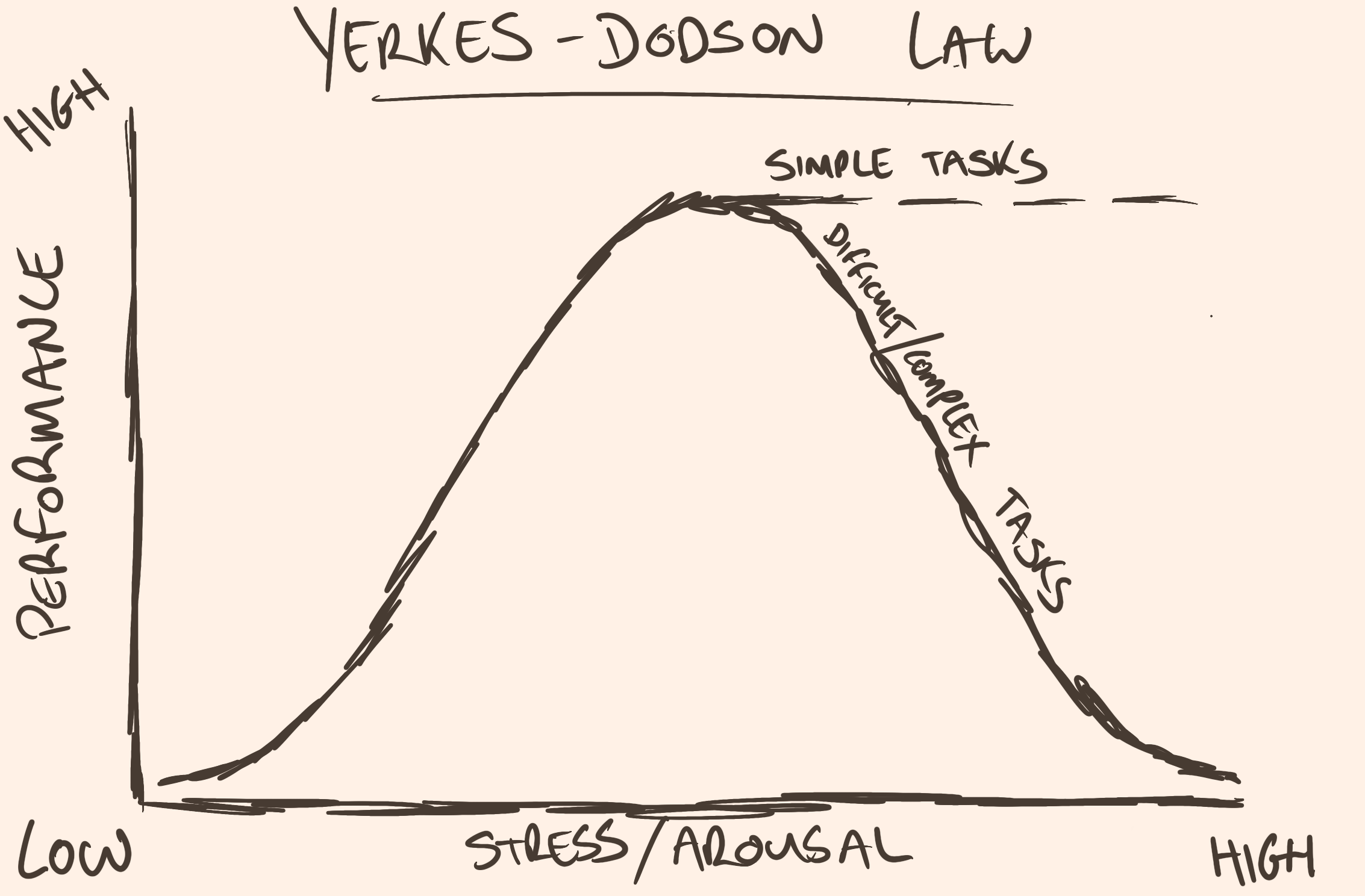

I’ve also spoken before about how the complexity of the task matters. If the task is really simple, then your performance isn’t going to decline when you’re stressed. It’ll plateau at optimal performance. Like, if the task is just to “pay attention to this thing that’s stressing you out”, it doesn’t really matter how stressed you get, you’re probably not going to struggle to pay attention to it. It’s only when the task is difficult or complicated that you’re going to see a decline in performance.

For simple tasks, continuing to increase arousal has no effect on performance.

Our performance increases to optimal levels and then remains there no matter

how stressed we are.

For simple tasks, continuing to increase arousal has no effect on performance.

Our performance increases to optimal levels and then remains there no matter

how stressed we are.

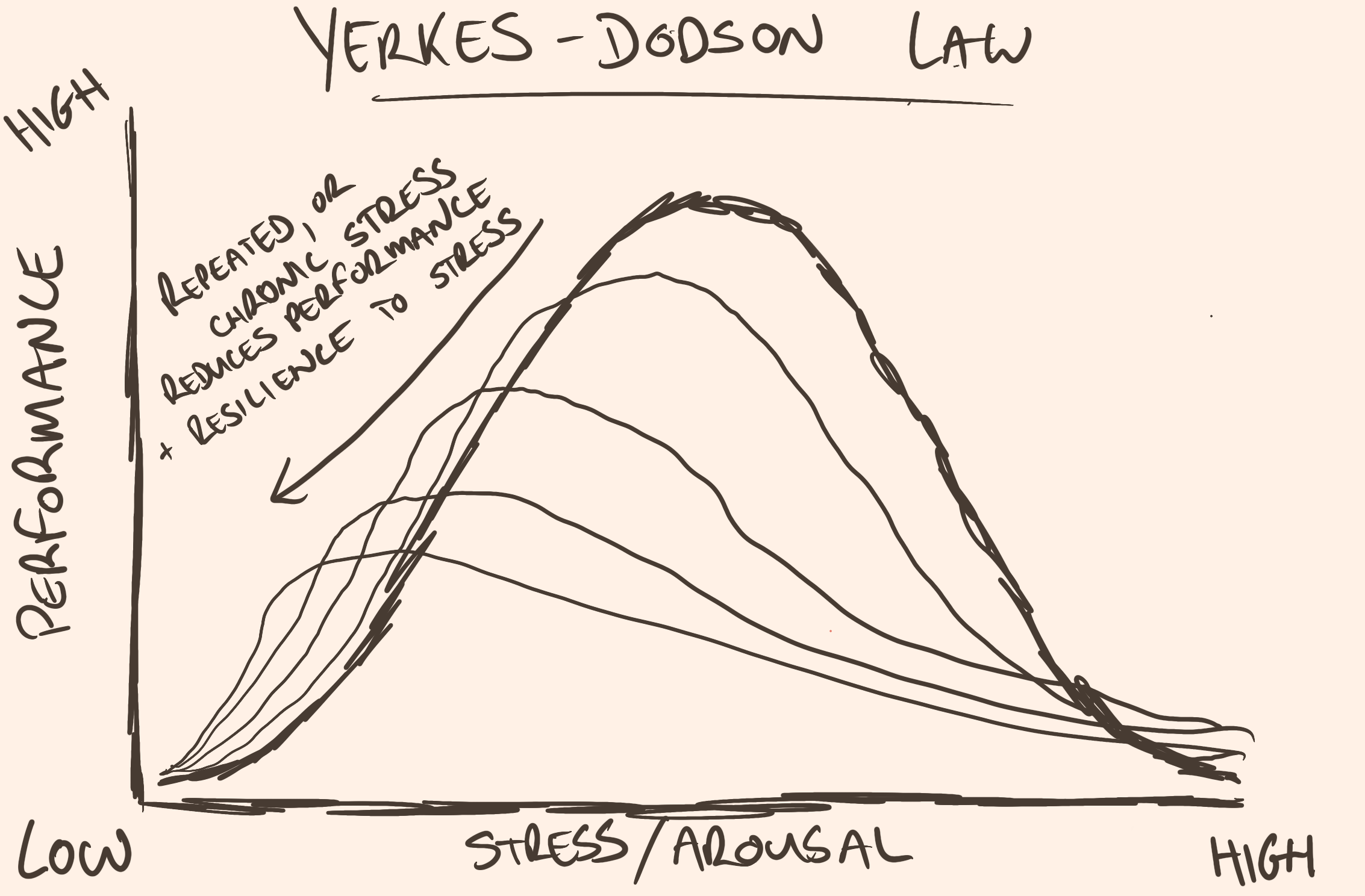

And lastly, perhaps most importantly, and again as I’ve talked about elsewhere, stress is a costly resource. You can’t just be stressed, and perform well, all the time. Over time you build up what some call allostatic load.2 It’s a sort-of catch all for the wear-and-tear the body experiences when repeatedly or chronically stressed.

Over time, repeated or chronic stress is going to reduce our capacity to

perform, reduce how much stress we experience as a positive force, and increase

the amount of stress we experience as negative. In biological terms, this is

called 'allostatic load': the wear-and-tear on our physical body that stress

induces.

Over time, repeated or chronic stress is going to reduce our capacity to

perform, reduce how much stress we experience as a positive force, and increase

the amount of stress we experience as negative. In biological terms, this is

called 'allostatic load': the wear-and-tear on our physical body that stress

induces.

You’ve got to use stress tactically. And you’ve got to give yourself a break. It’s no good trying to optimise your stress curve if you’re so stressed all the time that it’s flat.

Bias vs noise. It’s what the brain does. Better to use it, than to be afraid of it.

I have at least one more article on this in me at the moment, and I’ll put a link in when it’s out.

This is an elaboration of the generic finding in animal models of behaviour. You should have to look far to find stuff on this, although I haven’t found the relevant Wikipedia filing. So in lieu of that I’ll provide the papers I put on my ppt slides here, here, here, and here is a more accessible commentary on that last article. ↩

See also the article on chronic stress which talks about essentially the same thing, though with a heavy emphasis on when things are particularly bad. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.