Navigating Moral Terrain

September 1, 2025

Excerpt: I wrote a series of papers on practical ethics. I didn’t really like those articles. It did, however, inspire me to write a 35-page treatise on the behavioural science of ethical behaviour. There’s no way you’re going to want to read that, so I made this instead. It’s not actually heaps shorter, but it’s hopefully a bit more readable. Plus, if you like how the water looks, I assure you, it’s plenty deep.

Ideology

I describe five levels that help understand how good people do bad things—neural, cognitive, situational, social, and cultural. Inject some norms into the stack, and you can explain (and predict) moral behaviour.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

I manage the ‘ethical leadership’ module at Sandhurst, among other things. The ethics of extreme violence is something that really bothers military leaders. Not just because they want to reassure themselves that they’re good people, even if they’re doing bad things. But also because people in the profession of arms are particularly prone to moral injury—the distress we experience from perpetrating, through action or inaction, acts which violate our moral beliefs and values. And also, frankly, because we keep doing atrocities, and this is very bad for PR.

But the lecture series on ethical leadership I took over suffered from a number of problems. You can see me grappling them in this article and this article and their related series. Suffice to say, the answers people have to the question of why good people do bad things, and their approaches to how not to do those things, aren’t very satisfying.

So I thought I’d have a go at addressing them, since ethical decision-making, like all decision-making, is a product of the mind, and as a brain scientist, I rather like to talk about the mind. Here (PDF) is the result. It’s a bloody treatise, based on my rather rough-and-ready article series, a bit of research, and a trip out to Westpoint to see how they do things. I’ll be publishing it, after review, in the Sandhurst Occasional Papers, but since few people will trouble themselves to dig through the whole thing, I thought I’d write a more reader-friendly overview here.

Treat this article like a taster. If you like how the water looks, I assure you, it’s plenty deep.

See also me applying ETHIC to the military decision-making ‘S-CALM’ model.

The three problems of ethical education

1. Ethical misbehaviour is never obvious, nor easy to correct

Now, this part isn’t in the paper, but it’s the place people usually start when they’re thinking about ethics.

The first problem ethics education suffers from is a strange kind of category error. The examples of ethical misbehaviour we choose are usually the worst possible illustrations to use to understand it. I’ll show you what I mean. The Stanford Prison Experiment is quintessential in this regard, so I’ll just copy/paste from a popuar source like Simply Psychology to show you the error in typical form:

Aim: The experiment was conducted in 1971 by psychologist Philip Zimbardo to examine situational forces versus dispositions in human behavior.

Methodology: Twenty-four male college students were screened for psychological health and randomly assigned to be either “prisoners” or “guards” in a simulated prison environment set up in the basement of the Stanford psychology building.

Realistic Conditions: The “prisoners” were arrested at their homes without warning and subjected to booking procedures to enhance the realism of the simulation. They were then placed in cells, given uniforms, and referred to by assigned numbers.

Results: Men assigned as guards began behaving sadistically, inflicting humiliation and suffering on the prisoners. Prisoners became blindly obedient and allowed themselves to be dehumanized.

The experiment had to be terminated after only 6 days due to the extreme, pathological behavior emerging in both groups.

Conclusion: The experiment demonstrated the power of situations to alter human behavior dramatically. Even good, normal people can do evil things when situational forces push them in that direction.

As I talk about elsewhere, the implication here is always that these circumstances come about easily. That people left to their own devices will surely descend into chaos. It might not be a reassuring message about the nature of humanity, but it does imply that the fix is just as easy—all one needs to do to prevent such a thing is timely intervention.

Sadly for that narrative, if not sadly for humankind, these kinds of catastrophic circumstances are far from easy to achieve. This was no naturalistic slide into abuse and compliance. Zimbardo and his team worked very hard to make his guards brutalise his prisoners, and worked very hard to make the prisoners believe that they couldn’t leave.

Even then, two thirds of the guards didn’t engage in sadistic behaviour, and the prisoners launched a full-scale riot rather than capitulate—not precisely ‘blind obedience’. Under these conditions, timely intervention wouldn’t do much at all. The pressure of Zimbardo and his team would handily outweigh one’s gentle calls to a higher ethical standard.

More generally, typical examples of catastrophic leadership—Abu Ghraib, the abuses of the Australian special forces, the British Post Office Horizon scandal, the Oxfam child abuse scandal—any of these, and many more, demonstrate circumstances that are so complex and rich in subtle unethical pressures, that they only become tractable problems after the fact. During the fact, any behavioural expert would be very pessimistic about the ability of any one person to change events. Indeed, in many of these circumstances people did try to change events, and events continued regardless.

Massive ethical failures like those we typically use to illustrate ethics are just not that interesting, for someone trying to be a more ethical decision-maker. These situations are rather difficult to achieve, and once underway, even harder to do anything about, both due to their complexity and also their spectacular rarity.

Which leads us to our second and third issues in ethical education, which are tightly related.

2. “Thinking it through” is almost never the answer

When massive ethical failures like these are presented in their most abstract form, it seems incredible that anyone could let these things happen. Almost no one wants ethical catastrophe, and these are clearly ethical catastrophies. If someone had just stopped and thought things through, surely they too would have seen what we see.

Based on something like this logic, ethical decision-making models assume that, by simply reflecting on the problem, these kinds of disasters could be averted. By stopping and thinking, everyone would recognise what we recognise with the benefit of hindsight. In my paper, I spend some time detailing models of ethical decision-making which do this. For this article, though, I will choose a rather more straightforward example, and possibly my favourite—the one the UK Home Office published this very same year (pdf):

The relevant, existing decision-making process should be followed to the point where you have a proposed decision.

Once you have a proposed decision, you should reflect and consider the potential impact of the decision.

Are there any ethical or unintended consequences in the proposed decision that concern you, for example where the decision is impacting the customer in a way that was not intended?

If you do not have any concerns with the impact of the proposed decision, you can proceed with the decision.

By reflecting on the ethical content, surely the ethical catastrophes we see people engage in will be averted. This is the typical approach in its most blatant form, but you will find similar logic in almost any model you care to name.

Sadly, and as I point out often:

[p]robably the most consistent theme in my articles is the fact that, although we like to think we’re rational creatures, we are far from it. Rather than try to fight it, around here I suggest we’re much better suited to trying to work with it. We hate the idea of that, though. We always have.

As I detail in my paper, “thinking things through” almost certainly helps us correct mistaken assumptions at times. However, it also often seems to simply act to rationalise our existing moral intuitions to ourselves. The best example of this is the phenomenon of moral dumbfounding. When presented with a scenario in which a brother and sister have sex, though the siblings use protection and do it somewhere incest is legal, people will often still argue that it’s wrong because the siblings might conceive a damaged baby or because such a thing is illegal. When those objections are corrected for the evidence presented, people will still feel it’s wrong, but be unable to articulate why—they are dumbfounded.

Here, we are thinking things through, but we aren’t thinking things through usefully. We’re just coming up with arguments, evidence be damned. In the military context, this is especially problematic, because our faculties of “reason” are particularly at risk under stress and time-pressure, or fatigue and emotional compromise.

Models that tell people to just “think things through” are a recipe for failure. We will return to this in more detail shortly.

3. Tell us how to do it, not just what to do

Our second problem—this call to reason: to “think things through”—directly informs our third problem. Many decision-making models tell us what to do, but not how to do it. They assume that, so long as everyone is stopping and thinking, we should be able to solve the ethical problem in front of us with just a little push in the right direction.

A good example of this is Kem’s “Ethical Triangle.” Kem says we should test a course of action against “three basic schools of thought for ethics”. For the first—rules-based ethics—Kem suggests one ask the questions “what rules exist” and “what are my moral obligations?”. For the second—consequence-oriented ethics—Kem suggests one ask “what gives the biggest bang for the buck” and “who wins and loses?” For the final school—virtue-oriented ethics—Kem suggests one ask “what would my mom think?” or “what if my actions showed up on the front page of the newspaper?” Then, we should go on to select the “best” course of action.

On the surface, this seems helpful. He’s even provided the specific questions we should ask ourselves. And in many cases it is helpful to triage an ethical problem. Certainly it’ll get you in the ballpark.

Sadly, simply knowing that something you’re doing would make your mother unhappy won’t always tell you how to do the thing that will make her happy. Knowing that a particular process isn’t giving the most ethical “bang for buck” won’t always imply which process would be better. The reverse is true too—knowing what would make your mother happy doesn’t necessarily tell you how to achieve it, nor does knowing what process does give most bang for buck tell you how to put it in place. Knowledge about what one should or shouldn’t be doing is under no obligation to provide insight into how one should do it.

This is made more troubling still by the fact that many ethical problems are made less clear by asking questions like Kem’s. What if “what your mom thinks” is at odds with “what rules exist”? Or what if “the biggest bang for buck” goes against your moral obligations?

Much ethical decision-making comes in such a form. Rushworth Kidder calls this the difference between a moral temptation—a right versus a wrong decision, or a ‘want’ versus a ‘should’—and a moral dilemma—a right versus right decision, or a ‘should’ versus another ‘should’.

As I speak about in my paper:

A brief tour of recent military scandals makes the problem concrete. Participants in the events at U.S. run Abu Ghraib prison, our own “Helmand Province Killing”, or the Canadian “Somalia Affair” were not ignorant of the Law of Armed Conflict; soldiers had been briefed, and laminated cards spelling out the rules were literally clipped to flak jackets.

Yet, the atrocities continued.

The point is, even if stopping and thinking was going to help us, knowing what we should be doing isn’t very actionable unless we also know how. How to stop doing the wrong thing; how to start doing the right thing; and how to choose between different kinds of right. If we’re speaking about what people should do, it seems like this should be the role of ethical educators.

The ETHIC Stack: illustrating mechanisms of moral behaviour

The difference between telling people what they should do and telling them how they can do it is the difference between prescription and mechanism. Ethics are, fundamentally, prescriptive. They tell us what to do. For the prescriptions to be useful, we must add to that an account of what contributes to moral behaviour—the mechanisms; the how doing happens. Only when we combine the two do have we properly done the job of ethical education. A combination of ethics and the science of behaviour.

Now, mechanisms are very specific things. People who think a lot about them tell us that we need three things:

- the mechanism’s “entities”: the (relatively) stable ingredients, or parts of the system;

- it’s “activities”: the things that those parts engage in; and

- the organisation: the way those things are linked together.

Usefully, one can illustrate these features using any kind of well understood contraption. So in a handheld radio sets any Officer should be familiar with, the antenna is an entity that captures the radiowave (activity). The tuner (entity) filters the wave to a specific frequency (activity). The heterodyning circuit (entity) drops that frequency into the audible range (activity). The amplifier (entity) boosts the signal (activity). The speaker (entity) converts it to sound (activity). The overarching organisation for this mechanism is clear: radiowaves are transformed into audible, intelligible sound.

Why do we need such incessant detail? Two reasons. The first is that without it, we fall into the same problematic patterns I described earlier. If one says simply that a radio is something that should turn radiowaves into intelligible sound, then we’ve stopped at prescription. You are not particularly any closer to making those waves something you can listen to. Yet, by describing the entities and their activities, we are going further to describe how that prescription comes about. You know what entities to collect, and how to organise their activities in such a way that waves become sound.

The second reason this detail is useful is related. By understanding the relation between activities and their entities, we can see where we can “wiggle” something to change the outcome of the process. For example, as the soldier who has had the reckless audacity to patrol into the hills has discovered, swapping her now useless short antenna for a longer one will help capture the lost radiowaves more effectively.

When it comes to ethical and unethical behaviour, we want to ask the same questions—not just what people should do, but also what are the cognitive and behavioural ingredients (entities), what do those things do (activities), and how do they come together to produce moral action (organisation)?

That is, more-or-less, what my paper is—an attempt to demonstrate this often neglected aspect of ethical education. Here I try to lay out some of the entities, activities, and organisations that seem to make up ethical behaviour. Importantly, this is more of a sketch of how these thing might possibly come together, not necessarily how they actually work. While the mechanisms I describe seem convincing enough to me, the idea is more to illustrate the kind of thing I think is missing from ethical education more broadly.

I call it the ETHIC stack,1 more for fun than anything else, to distinguish five important levels in moral behaviour:

- E: the early, emotional circuitry;

- T: the thought patterns and cognitive-social schemas;

- H: the immediate habitat (really, the situation);

- I: the in-group and social dynamics;

- C: the cultural, command, and institutional scaffolding.

At each level I sketch a specific mechanism, drawing on relevant theory from the literature in the sciences of mind, to illustrate the kind of thing I mean. Treat it as a tool to amplify any discussion about what kinds of behaviours should be occurring with some ideas about how those behaviours might be generated.

Should you mislike my layers, or my candidate theories, then by all means choose your own. The appendices of my paper are a good place to start—I’ve collated plenty more ways to skin this cat.

Lastly, if you don’t like to read, I’ve created a NotebookLM—an AI you can chat with to discuss the ideas in depth. It also managed to produce a pretty good podcast on the subject.

For me, though, reading and writing is where the magic happens. So, let’s begin.

Early Emotional Circuitry: the “pattern detector”

The mechanism I describe at this level is roughly based on the work of Lisa Feldman Barrett’s “Active Inference” theory of emotion and George Mandler’s “Interruption Theory” of emotion.

We’ll start with moral “intuitions”—what some2 would call the basic unit of moral decision-making. We might call the entity at this level of our mechanism the “pattern detector”.

You see, a great deal of our neural infrastructure is devoted to the unconscious ‘tagging’ of stimuli with valence—a visceral sense of goodness or badness. This tagging is based on patterns we detect in those stimuli—patterns which serve as predictable omens of positive or negative experiences. Based on these experience-derived patterns, our affective circuitry injects a small amount of valanced arousal into the system to urge us to approach or avoid, to feel excited or threatened, to nurture or be disgusted.

This is the impulse that has babies reaching for colourful toys, or you recoiling from disgusting smells. That same visceral goodness and badness seems to apply to moral categorisations too. I tell you that someone just pushed past an elderly woman in the coffee queue, and your pattern detector will have already tagged that as ‘bad’: a small spike of arousal in response to a sense of unfairness, and an urge to signal your disapproval.

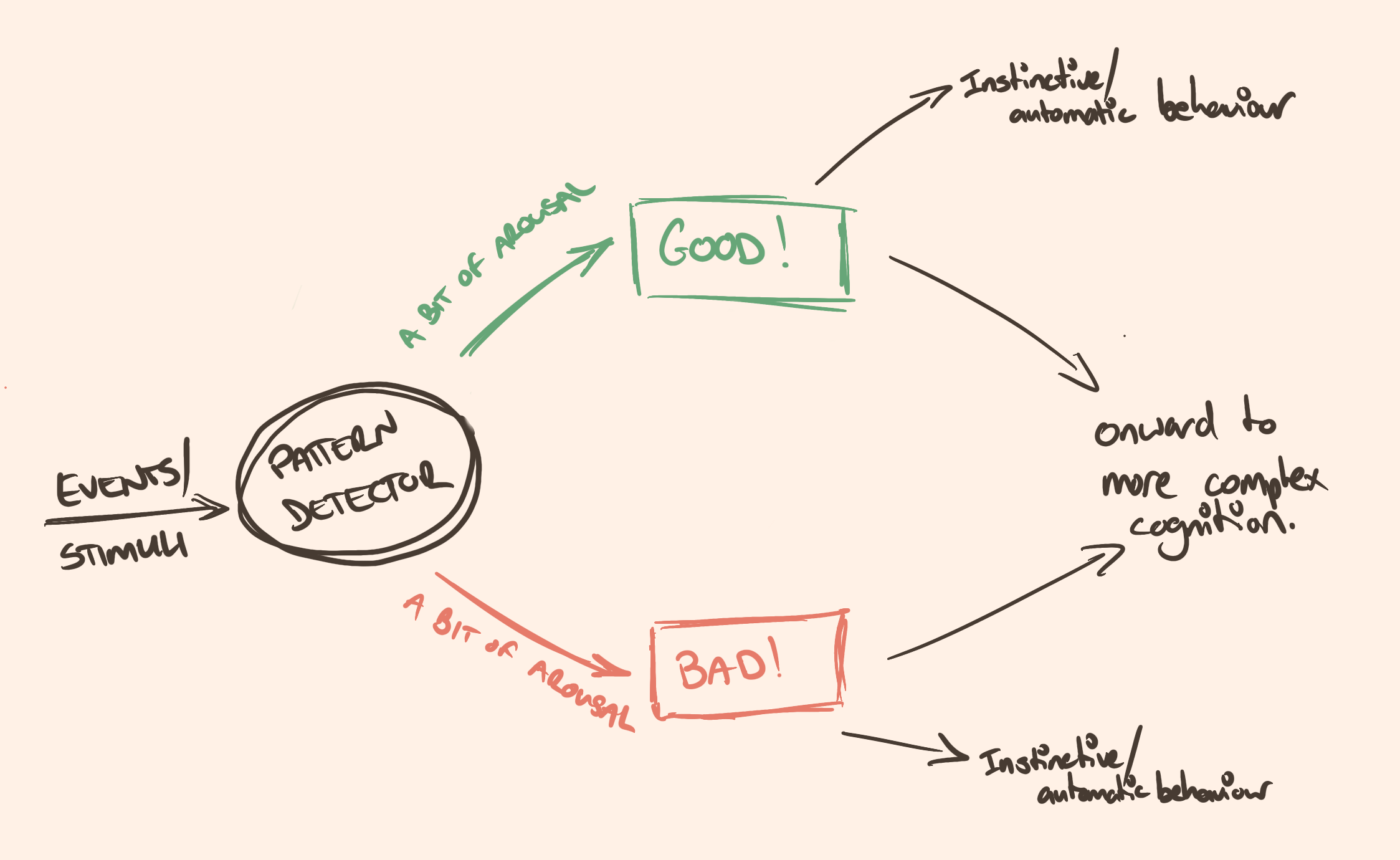

Our 'pattern detector' stands in for everything in your nervous system tuned to processing input. One fundamental job of the nervous system is to detect patterns in that input, and assign a very basic valence: a sense of goodness or badness. Either way, it also injects a bit of arousal to initiate urges to approach, if it's good, or avoid, if it's bad. You might get some instinctive behaviour for free at this point, like dodging out of the way of something fast moving towards you, but mostly this "intuition" gets passed onwards for more complex cognition. This is true of all intuitions, including moral cognitions.

It can be more complicated. When a team meeting comes to a conclusion, after the jittery junior finishes their piece, you do your best to catch their eye and smile—reassure them they did a good job. You don’t stop to think, you simply follow a pattern of thought and behaviour you’ve been socialised to engage in. Equally, should the meeting chair have skipped the junior, whose work underwrote the entire presentation, you’d recognise that pattern too, and respond in kind—a little energy surge might drive you to put your hand up, and point out that perhaps we should hear from the junior before moving on.

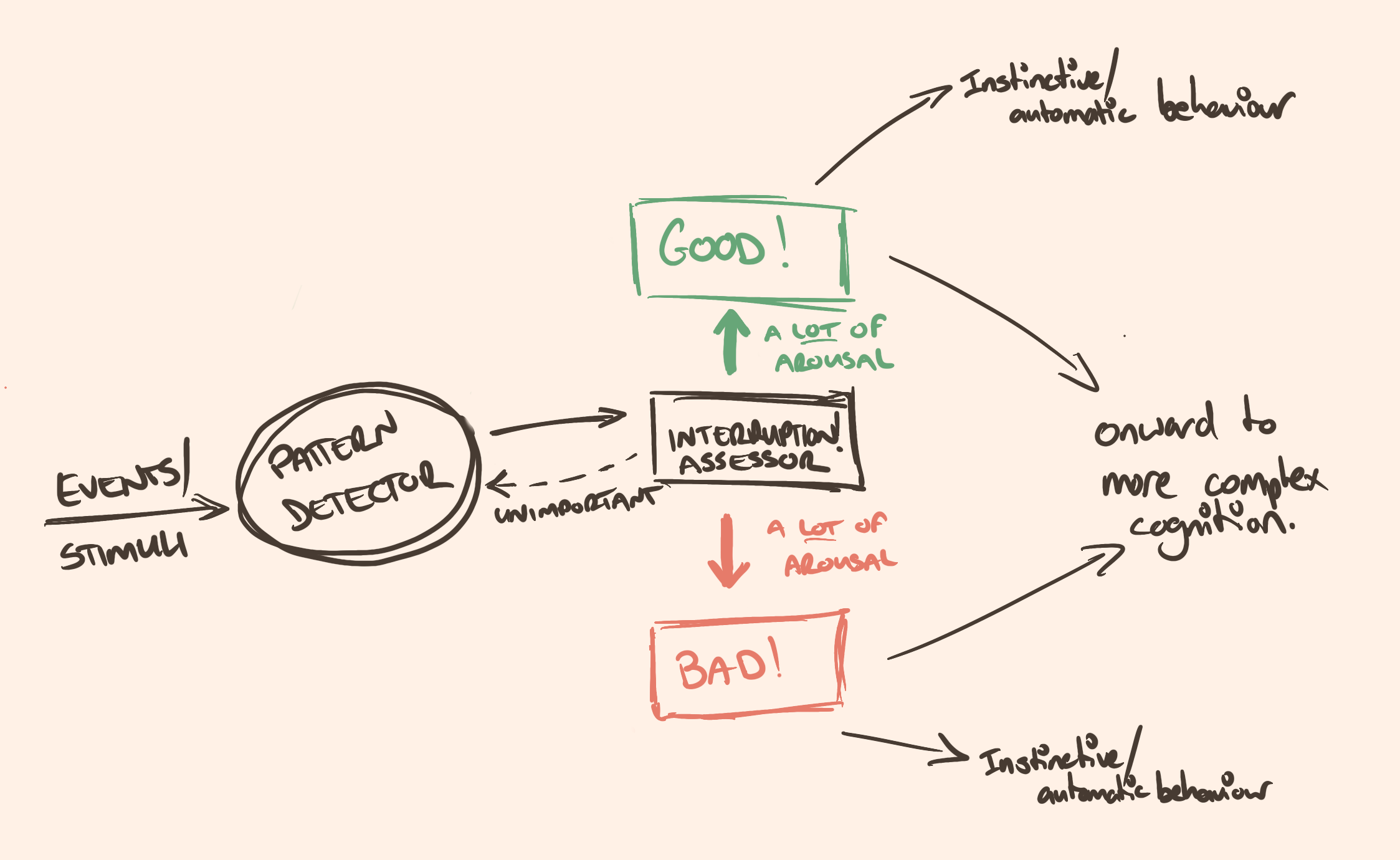

Indeed, we might add to our pattern detector an “interruption detector”—an entity which drives us to troubleshoot violations of our expectations, because pattern violations are much more obvious drivers of moral behaviour. The slighted elderly lady in the queue, or the skipped junior who worked all night on the slides are both examples in which your ‘fairness’ pattern detection was violated. Where only a small amount of energy would have been devoted to stepping aside for the lady, or smiling at the junior, a great deal more is injected when you need to do something about a queue-jumper or a disrespectful boss.

Our 'pattern detector' doesn't always detect patterns. Often, it detects interruptions to patterns. If someone pushes an elderly lady out of the way of a queue, your 'queuing' pattern has been interrupted. In this case, your 'interruption assessor' has a job to do. Does this interruption match some other pattern? If so, we can pass it back to the pattern detector as normal. If not then it will inject quite a lot of arousal to motivate your system to learn this new pattern. In practice, it's very similar to other intuitions, just stronger.

All of this happens within mere milliseconds—the detection of a pattern, or the detection of an interruption to patterns we expected. These things we might call our moral intuitions, and the intuitions formed here go on to influence both our conditioned, more instinctive behaviour, as well as influencing more complex cognition like that at the next level of our multi-level mechanism.

The implication of such a mechanism is really very simple. This most basic task of the nervous system—the detection of patterns and their violations—happens pre-consciously, very quickly, and influences all other behaviour from the bottom up. If I hadn’t convinced you that asking people to “stop and think” wasn’t very bright in the previous subheading, you should certainly be worried about it now. Instead, we must train intuitions. The person who never learned that pushing in line was unfair, or skipping the junior was an ethical failure, would never step in to rectify the situation.

The only way to train our intuitions is to practice. Either in morally challenging environments, or by talking through scenarios formally and informally—moral case deliberation, as it’s known. To have a more ethical pattern detector, we need to train it on ethical patterns.

Thought-level schemas: the “lazy controller”

The mechanism I describe at this level is roughly based on the notion of cognitive control in cognitive neuroscience, and Albert Bandura’s moral disengagement mechanisms.

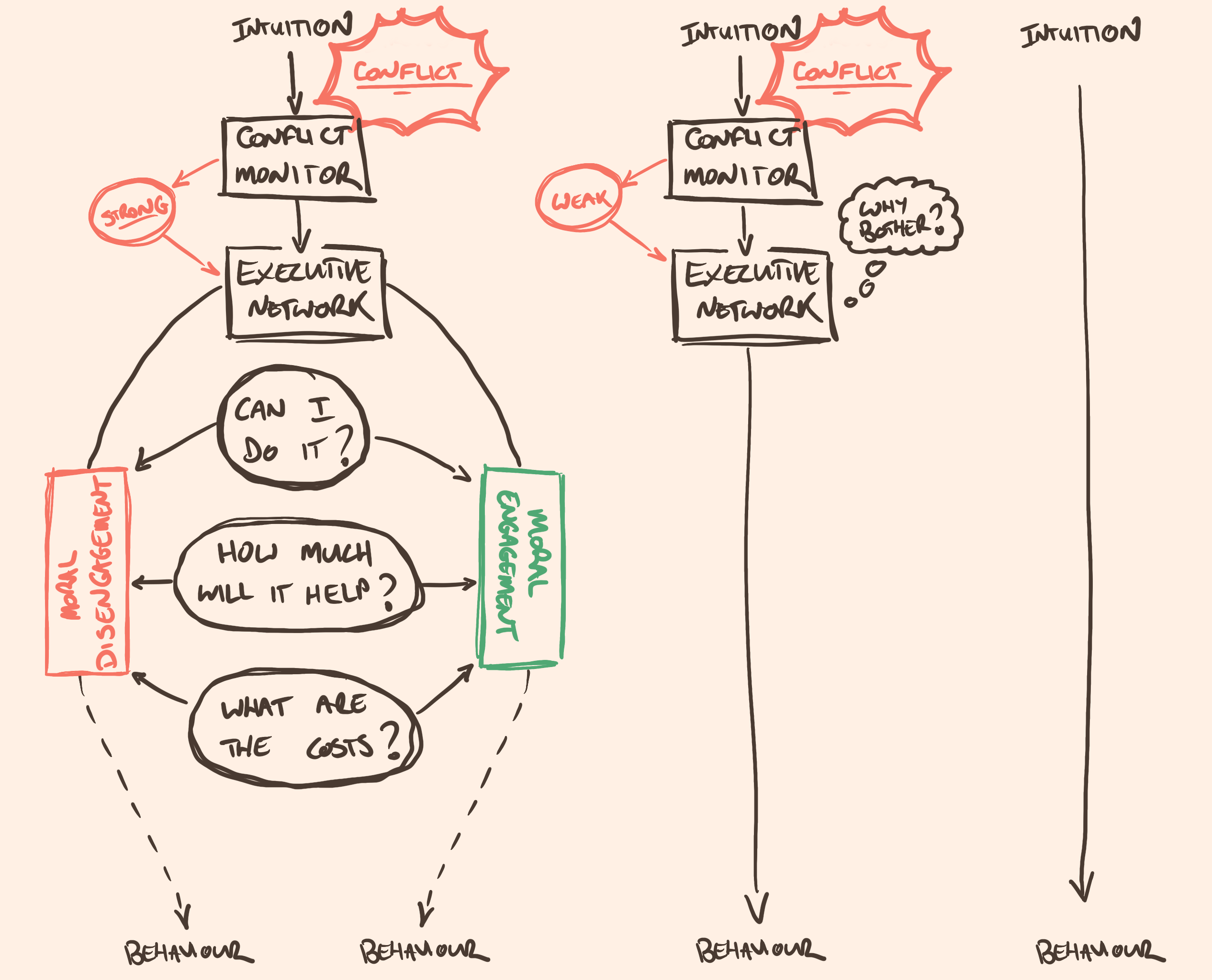

The next entity in our mechanism stack we might call the “lazy controller”. We must call it lazy because it would prefer never to work. You see, typically, our intuitions drive our behaviour—these intuitive verdicts formed at the E-level pass straight through into action. Most of the time, we act as if on autopilot. Automatic responses to the familiar patterns of our lives dominate our behaviour.

However, at times, autopilot isn’t sufficient. At times, our intuitions clash, or the stakes make us more likely to question them. It is only then that something different will happen. Neuroscientists refer often to the “conflict monitor”, a network of regions highly attuned to cognitive conflict like this. It will register the scale of the clash, and hand things over to an “executive network”—our lazy controller—whose job it is to determine what to do to resolve the conflict.

The phenomenon of moral dumbfounding demonstrates that this something is, very frequently, nothing at all. As I said earlier:

When presented with a scenario in which a brother and sister have sex, though the siblings use protection and do it somewhere incest is legal, people will often still argue that it’s wrong because the siblings might conceive a damaged baby or because such a thing is illegal.

Here the E-level has detected a pattern, or perhaps a pattern violation—incest. An intuition this acute is rarely going to be questioned, and the behaviour that follows will be some form of disapproval.

However, in the experiment this vignette comes from, the participants encountered a minor conflict in the form of the researchers asking them to explain why the incest was wrong. Here, we would assume that our faculties of reason would switch on to deconflict the cognitive clash.

Instead, however, we see the laziest form of reason—motivated reasoning:

When those objections are corrected for the evidence presented [they used protection, and did it in a country incest was legal], people will still feel it’s wrong, but be unable to articulate why—they are dumbfounded.

Here, we are thinking things through, but we aren’t thinking things through usefully. We’re just coming up with arguments, evidence be damned.

When conflicts are small, or not worth overcoming very seriously, our lazy controller will just do whatever it must to go back to “sleep”. This does not require being correct, only rationalising the most convenient option. Typically, that option will align with the initial intuition. Engaging in this kind of conflict resolution is costly you see, and the lazy controller is not eager to spend its energy.

By default, intuitions formed at the E-level will pass directly into behaviour (left). Only when there is a reason to, like when there's conflict, will our faculties of thinking come online, and then it will do only whatever it needs to do to go back to 'sleep'. You can see why: look how much mental infrastructure thinking takes (right). It's very costly. In this case I have simplified it for moral decision-making. Our 'conflict monitor' tells us how much conflict there is, and passes it to the 'executive network': our 'lazy controller'. The executive network is going to solve the conflict by asking three questions: 'can I do anything about this', 'how much will my thinking about this help', and 'what are the costs of thinking about this'? When it comes to moral conflict, we're speaking about whether the person feels confident to engage in the moral conflict, has experiences being successful navigating moral conflict, and doesn't find considering ethical content very difficult. If so, then they're more likely to engage with the moral content of the decision, rather than disengaging and passing it off.

This is where we might quickly consider some mini-mechanisms—Albert Bandura’s “moral disengagement mechanisms”—linguistic, or cognitive manoeuvres that help us rationalise unethical behaviour. Euphemistic language (‘collateral damage’), advantageous comparison (‘others did far worse’), displacement of responsibility (‘I was just following orders’), distortion of consequences (‘she’ll be fine in the morning’), among others, are all ways in which the lazy controller tries to shirk its duty and go back to “sleep”.

The implications at this level, our ‘lazy controller’ laid out thus, are also clear. Firstly, we want to generate moral conflict—if no clash of ethical alternatives is detected then our moral intuition, passed up from the E-level, will drive our behaviour, for better or for worse. This is where the standard ethical education excels—training in ethical frameworks and considerations helps sensitise us to moral content.

We have to go further, though, and also train ourselves to morally engage, rather than lazily disengage with moral content. In a similar fashion to our E-level pattern training, we must train the ability to detect and eliminate Bandura’s moral disengagement techniques, and replace them with their opposites—direct language, legitimate comparison, acceptance of responsibility, clarification of consequences, and so on.

The lazy controller will always be lazy, so we must simply change what the laziest option is. Fortunately, we can augment that at the next level of our stack.

Habitat (really, the situation): an “affordance auction”

The mechanism I describe at this level is based on what’s known as the Affordance Competition Hypothesis, which is a cognitive neuroscientific approach to Gibson’s theory of “Affordances”.

This is really a very silly name for the layer, but it makes the ETHIC mnemonic stick, so we shall persevere.

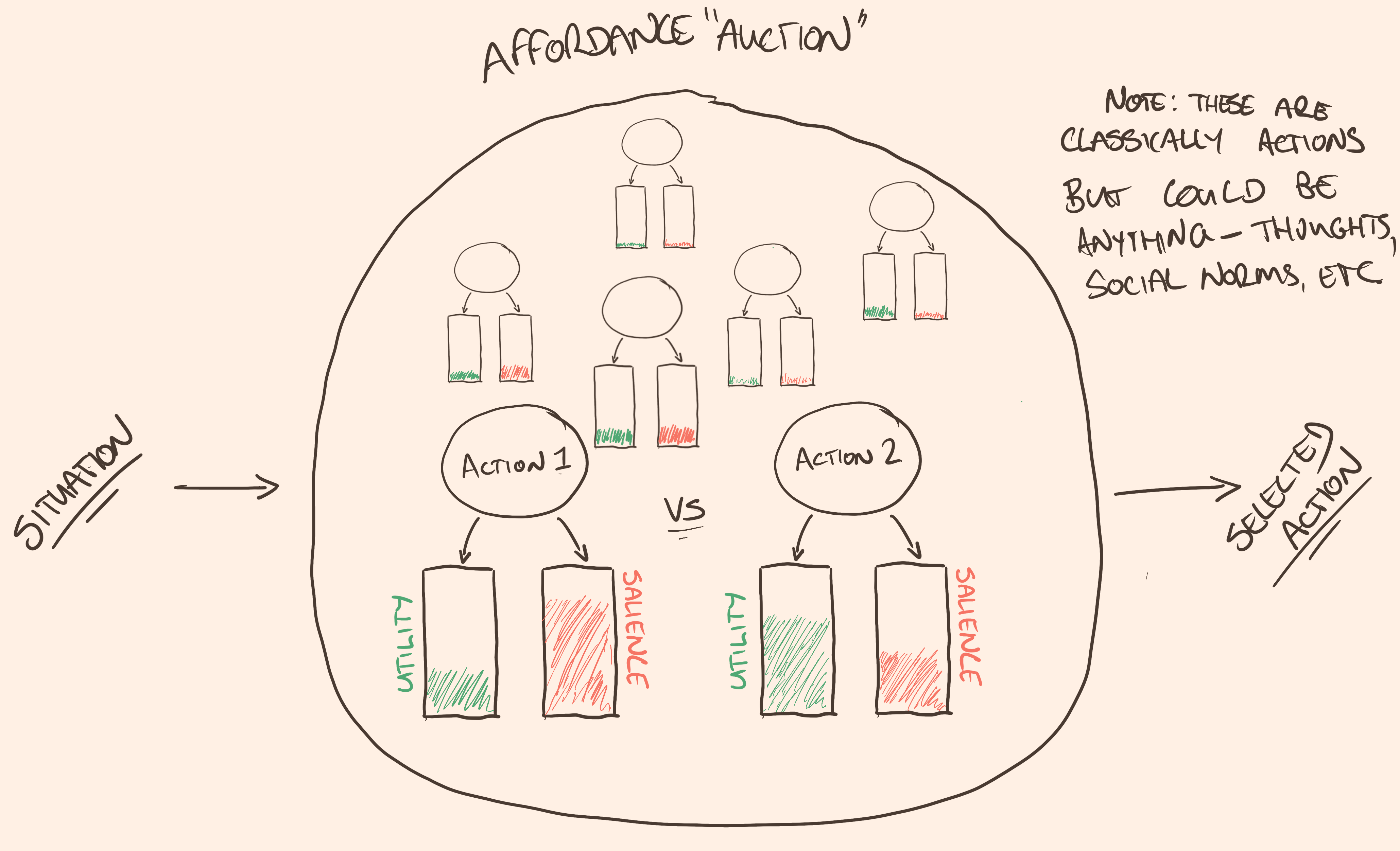

This level is where we account for how the environment can rig the race from moral intuition to behaviour. You see, our motor-system doesn’t weigh every conceivable course of action. Instead, it scans the environment for affordances—opportunities for action that the environment presents. When you step onto a lurching subway carriage, the vertical poles don’t just exist nearby—they invite you to grasp them and stabilise yourself. If the subway carriage is nice and smooth, and a seat is open nearby, you ignore the vertical pole, and move toward the seat instead. Two variations in the situation, two different affordances become obvious to you. We might call the entity at this level, then, the affordance auction, which decides the most valuable action-plan based on the affordances in the environment.

The likelihood that we’ll choose one ‘affordance’ over another is based on its:

- salience: how close, or visible, attention-grabbing, or obvious the features of the environment that support a plan of action are; and

- utility: how much the plan of action is going to help you solve a problem, versus the costs of doing so.

You think about a time where you’ve walked past a trivial safety hazard—the fire door is wedged open perhaps, or a security door, and some colleagues are standing off in the distance having a smoke-break. Then let’s assume that our pattern detector at the E-level is well-enough trained to catch this inappropriate pattern, and pass that intuition up. Our T-level controller detects a conflict—loyalty to your colleagues laid against a concern about the risk of harm—and has reluctantly been brought online. The environment, then, will provide us a couple of “affordances”. Let’s consider them.

The environment 'affords' certain opportunities to act. We can imagine a kind of auction in which each of these is weighed against others to determine what you will do. For example, on a lurching subway carriage there are at least two affordances. On the left, Action 1, we have 'grab the pole'. On the right, 'Action 2', we have 'go sit down'. Now, we must assess them for how salient (obvious) and how much utility (usefulness) they have. Grabbing the pole is very salient---the pole is right there. It's also going to stop you lurching around, so it's useful enough. Sitting down would be better---a much less tiring way of dealing with the lurches---but the seats are all the way over there, so sitting down isn't really that salient. Grabbing the pole wins. There are lots of other affordances too. You could always do a handstand, or start singing, for example. These aren't really salient or useful at the moment though, so they sit in the background, unconsidered.

Perhaps you remove the wedge, and let the door close. It’s a salient choice—the wedged door is right there in your path. It’s going to help too—the safety hazard will be resolved instantly. The colleagues, though, represent a cost—should you call out to them? Will they tease you, or dismiss you? If you don’t call out, will they be mad?

So perhaps instead, you keep on walking. This could be salient too. Hands full with a laptop and a tray of hot drinks, the lift doors are closing ahead, your phone is vibrating with messages telling you you’re late for the meeting. Ignoring the problem and walking away is a very attractive solution to solving this problem now. To boot, no one’s going to yell at you for ignoring the door, the only cost is the very low risk of a security breach or a fire hazard getting out of control.

There are other affordances too. You could always do a handstand, for example, or start singing “Waltzing Matilda” at the top of your lungs. These exist in your repertoire of action-plans, but the utility and salience are so low that neither are in contention.

Our affordance auction makes the implications of this kind of environmental calculus clear—we must drive up the salience of ethical behaviour, and emphasise its utility. We want to raise the value of the ethical affordances and lower the friction of executing it. A safety brief that emphasises just how quickly a fire can kill everyone on a floor might be just enough to push you over the edge, or a sign so vivid that your colleagues flaunting of it makes you irritated.

What’s also obvious from our mechanism at this level that affordances aren’t very straightforward levers for intervention. The situation drives our behaviour and, in the moment, there is often little we can do about it. A theme is emerging—deliberate training and ongoing sensitisation to moral content outside of the situations we find ourselves in are a critical factor in the successful navigation of moral behaviour.

However, our next level is quite the opposite—I suggest it is perhaps the straightforward to manipulate.

In-group Dynamics: the “prestige engine”

The mechanism I describe at this level is roughly based on notions of Social Identity: Brewer’s Optimal Distinctiveness and Reicher and Haslam’s ‘engaged follower’, as well as a little Social Capital theory.

Given how much of the human experience is determined by social factors, the social environment deserves special treatment. In the previous example, the presence of unethical colleagues acted to reduce the value of the ethical ‘affordance’ and, indeed, it’s frequently the case that the people around us will determine how ethical our behaviour remains. Unlike other habitat (situational) factors though, the social environment is rather easy to manipulate.

We’ll call the mechanism at this level the “prestige engine”, because the collection of entities I want to describe are a little more complicated.

The first entity we should talk about is the store of social norms. Norms are derived from the groups we surround ourselves with, but they don’t always belong to one group over others. For example, laughing at people’s jokes, even when they aren’t funny, is a social norm. You do this in your group of friends, but you also do this with your work colleagues. So we have to consider norms independently of their groups. The activity norms produce, though, are certain kinds of behaviour. Norms drive behaviour. We might think of it like the steering wheel of the engine.

Obviously, though, social norms don’t drive behaviour without the groups that promote those norms. You might laugh at your friend’s or your boss’ bad jokes, but you’re not going to laugh at bad jokes when you’re watching TV at home. Indeed, this is the reason sitcom laugh tracks exist. Importantly, though, it’s not just the group that matters—it’s the representatives of the groups. You might laugh at the bad jokes of a friend who is always in your friend group, but you’re much less likely to laugh at the jokes of a friendly acquaintance who very rarely hangs out with your group. You might laugh at your boss’ jokes, but not at the jokes of the temp worker who’s there for the week.

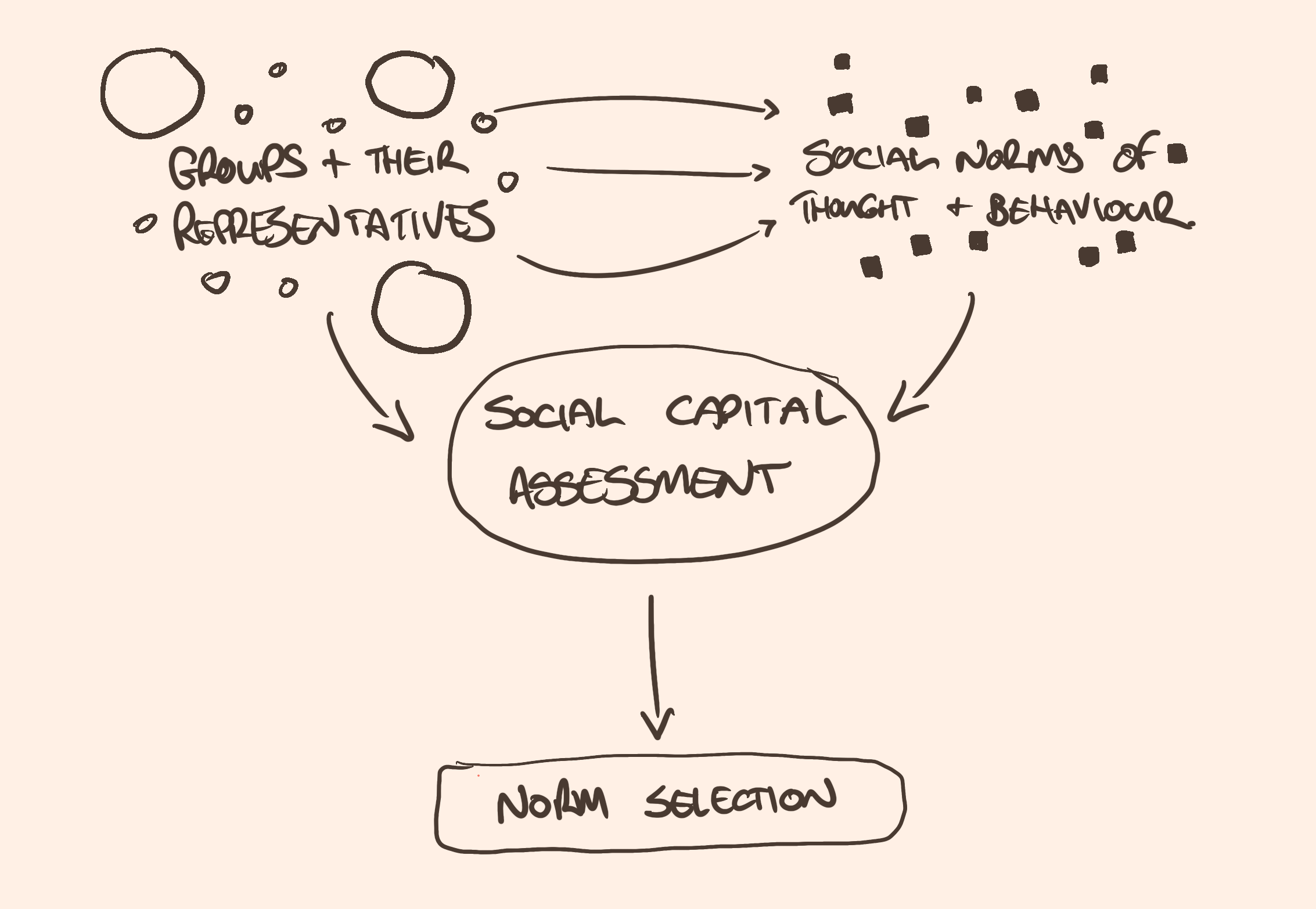

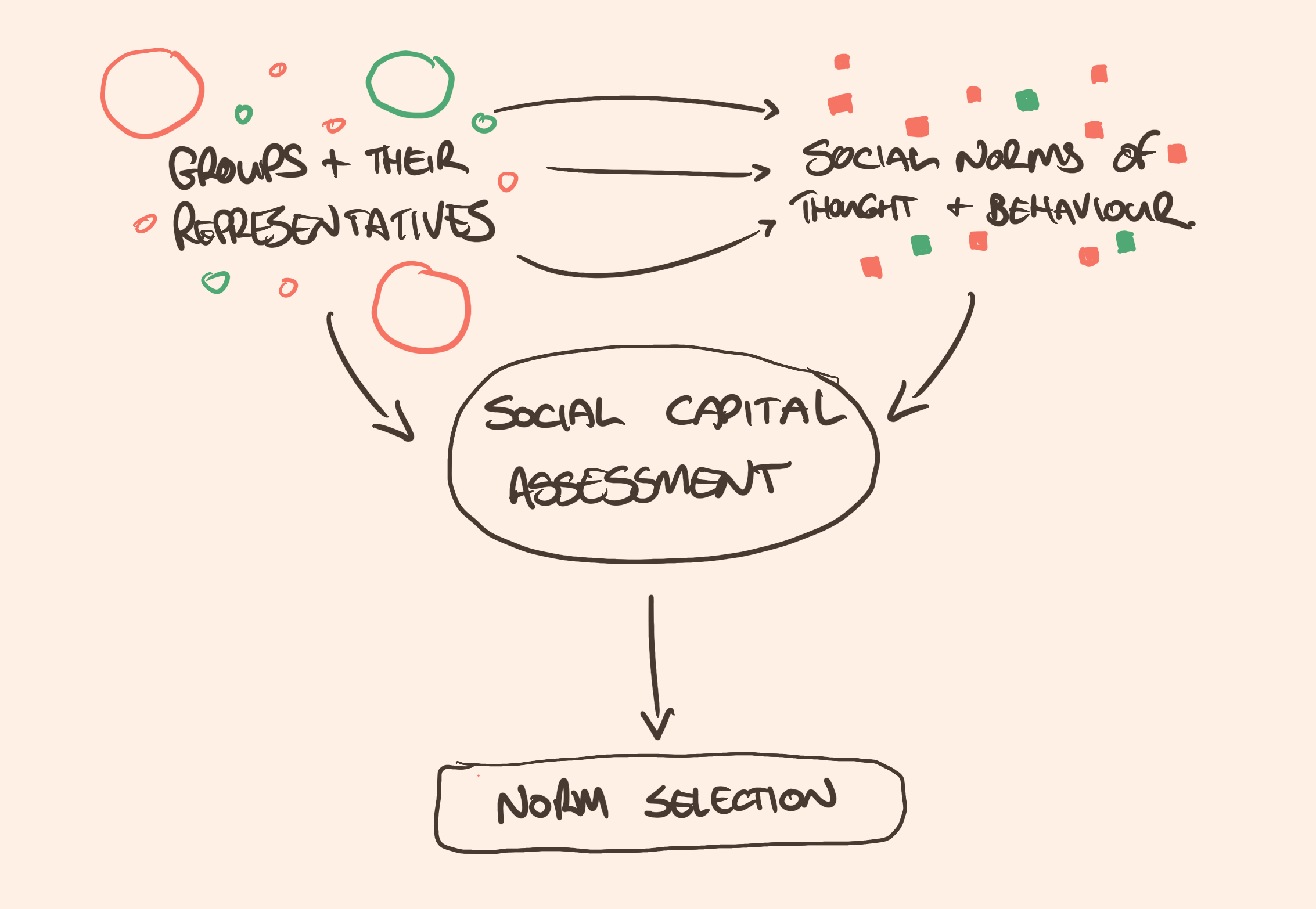

Our 'prestige engine' consists of groups and, more importantly, their representatives. Without representatives, groups aren't very influential at all. These groups all generate social norms---ways of thinking and acting. Typically, groups share these. It's not very often that a social norm is something only done by one of the groups around you. Your 'social capital assessor' will consider the groups and their representatives, and consider the social norms on offer, and based on this information decide how much social capital you stand to gain selecting some norms to conform to over others.

So our second entity is the group, but particularly the representatives of that group. The extent to which the people around you represent the group acts like an accelerator—amplifying the kinds of behaviour steered by the social norms that group implies.

We need at least one more entity for our prestige engine to be complete—the fuel. The fuel comes from the social capital we derive from acting in accordance with the social norms. Social capital is a complicated concept, but we might simply summarise it as “the value a group provides that you couldn’t provide yourself”. Often this comes in the form of status, or belonging, or reputation. Sometimes it’s quite tangible though—access to things you wouldn’t have access to for example, or the ability to make connections you might otherwise not be able to. For our illustration here, let’s just concentrate on status.

Let’s say the joke we know we’re supposed to be laughing at is offensive. Racist perhaps, or sexist. You would prefer not to laugh at it. You might even prefer to correct it—your pattern detector has flagged it as a no-no; and your lazy controller is online, conflicted between group loyalty and not being a jerk. If it’s your friend group, then you’re not going to lose much, if any, social capital by not laughing along with the joke. Your friend group, ideally, is about much more than this rather superficial fitting in, and so the social capital comes from other places—how much emotional support you provide each other, or how good you are at the activities your group engages in.

At work, it might be a different story—not laughing along with your boss or your colleagues might have rather uncomfortable social consequences. Work colleagues are often much more superficial relationships, and sometimes the only social capital you derive is from this kind of superficiality. As such, you stand to lose much more social capital by not going along with the joke.

So, social capital is the fuel which makes the prestige engine run.

Importantly, the selection of social norms to adopt requires comparison to other similar groups. Without norms that distinguish the group from others, there is no way to "belong" to it. As such, the comparison groups are an almost invisible lever in the manipulation of social identity.

There is one final ‘entity’ that drives our prestige engine though, an entity that’s almost invisible. The prestige engine doesn’t even turn on without comparison groups. There’s no such thing as prestige without contrast because groups only stabilise social norms that mark a valuable difference between them and other, similar groups. There needs to be an out-group for you to gain social capital as part of an in-group. If, in the workplace, “we can take a joke” is the badge that distinguishes your team from other teams, then laughing at jokes is the norm you’ll adopt. If laughter isn’t a part of what makes your team a team, then you won’t feel nearly so compelled to gee up your boss. Instead, you might find yourself compelled to go through bureaucratic rigmarole, or gossip about how John always sends emails after work hours. The social norms that drive our behaviour are the social norms that help us demonstrate our group membership—they help us distinguish ourselves as a part of this group and not other, similar groups. Comparison groups are like the ignition switch for our prestige engine.

It might seem complicated, all these different entities, but it shows you just how many levers exist at this level of the mechanism to drive ethical, and not unethical behaviour.

Anyone who has been through high-school will recognise the value of targeting the fuel—if ethical acts cost status, they’ll be rare. If they pay in prestige, they’ll spread. Rewarding ethical and not unethical behaviour within the context of the group so that it acts as a source of social capital is as simple as publicly praising or sanctioning them.

The prestige engine provides more levers for action than the fuel, though. You can act on the ignition, for example—providing comparison groups that emphasise certain target behaviours (social norms) over others. If these friends make off colour jokes, then maybe you might lightly remark that those are the kinds of joke some less desirable out group would make. Or, speak about other friends who might also find those jokes distasteful to change the group perspective about what is in and what is out.

Or you can target the representatives themselves—making sure that the leaders and more charismatic members are aligned on what norms they should be demonstrating, because they are the ones determine what collection of norms the group implies to the others.

All of these things drive the other levels. Conflicts at the T-level are often sparked by disagreements between behaviour and the activity of the prestige engine, and how invested the lazy controller is at resolving that conflict is just as often determined here too. The pattern detector is highly context sensitive, and the in-group context is where it takes many of its cues from. A distasteful pattern might not be noticed if no one in the in-group shows any sign that they’ve detected it too.

Lastly, it should be made explicit that, as the level of the stack with the most mechanistic leverage, it might be our greatest opportunity to drive ethical change, but equally it is often the greatest risk factor for unethical disaster.

Cultural and institutional scaffolding: the “enforcement infrastructure”

The mechanism I describe at this level is based on Gelfand and colleagues’ work on “tight” and “loose” cultures—how threat environments activate monitoring networks and sanction systems that constrain behaviour.

Our last layer appears the least manipulable, but may offer more leverage than initially obvious. We’re speaking of the broad-brush cultural and institutional values that cascade through the other levels of the stack. Think of “democratic values”, or “Judeo-Christian sensibilities”. The kinds of thing an organisation or country or ethnic group might say about themselves.

This is a critical level to pay attention to. Without this level, the ETHIC stack isn’t an account of ethical behaviour, but a terribly incomplete account of any behaviour. We aren’t interested in all behavioural mechanisms, just the ones that seem to contribute most to ethical behaviour, and we can’t understand that without injecting some cultural norms into the system.

But culture doesn’t just supply the content of norms—it also supplies the infrastructure that enforces them. This is where the mechanism gets interesting.

Think about military versus civilian organisations working side-by-side. Military units operate under constant assumed threat—even in peacetime, the mission is threat-response. This creates permanent coordination pressure: people need to align their behaviour. Combined with high personnel density (rank structure ensures you’re observed at every level) and immediate sanctions (from spot corrections to disciplinary action), the result is a tight culture. Everyone monitors everyone, violations get caught quickly, and consequences are certain.

Civilian organisations operating alongside military units experience something quite different. Lower assumed threat means less coordination pressure. Personnel density is lower (autonomy is valued, peer observation is minimal), and sanctions are slower and less certain (performance reviews happen annually, consequences are vague). The result is a looser culture—not because civilian personnel are less ethical, but because the enforcement infrastructure differs.

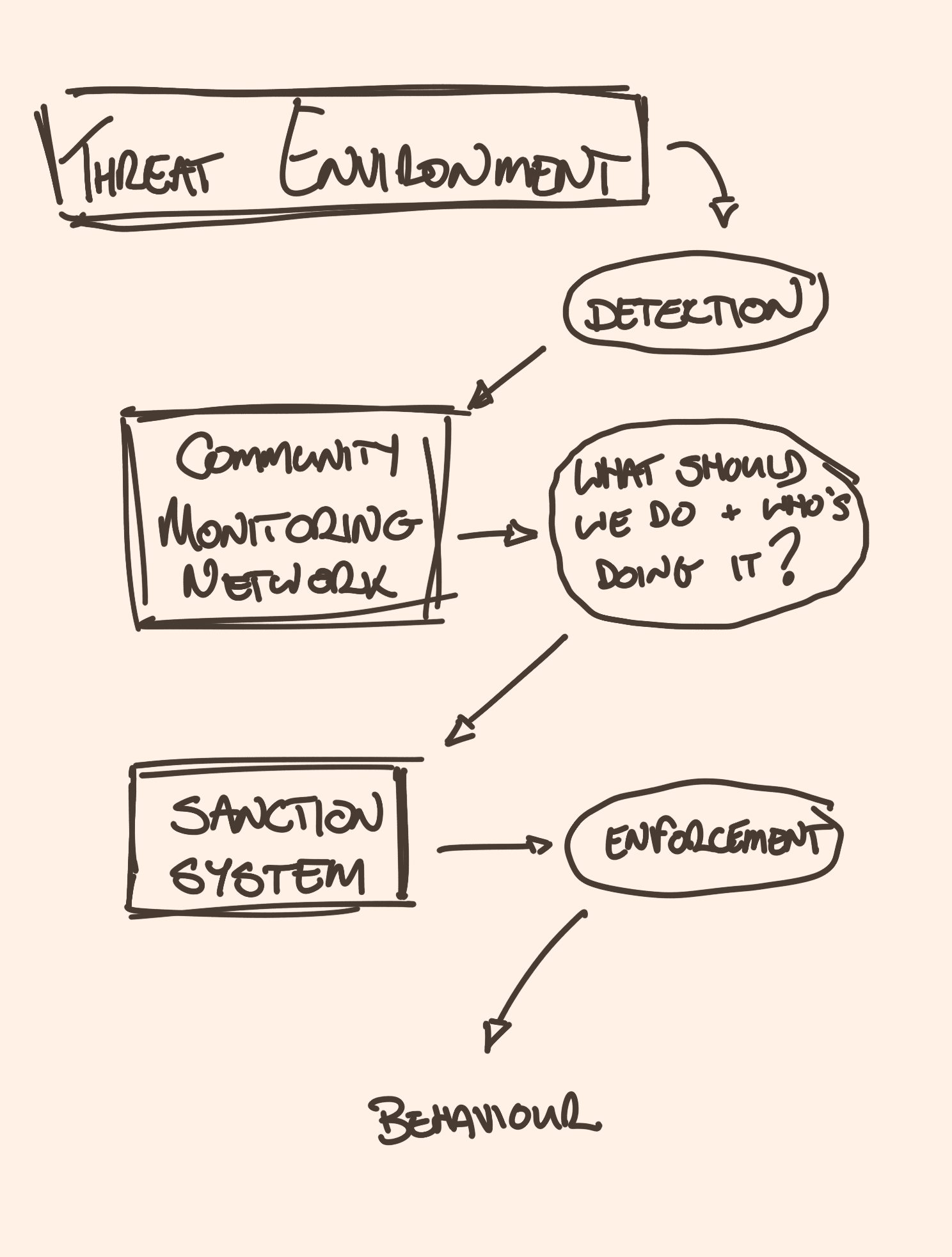

We can think of a mechanism with three key parts, then: threat environment (real or assumed), monitoring networks (who watches whom, and how often), and sanction systems (how consistently violations trigger consequences). Higher density of interactions means more monitoring, which means higher detection probability, which makes sanctions more certain, which tightens behavioural constraint.

This one isn't that complicated. Community monitoring networks detect threats and determine how people should behave as a response. Sanctions enforce that behaviour. Both monitoring networks and sanctions can be formal or informal, and threats can come from the outside world, or from within the culture. The key organisational feature is density---more people watching means more enforcement. Of course, all of this assumes a culture with norms that should be followed.

What makes this useful is that it gives us levers. You can’t easily change the threat environment or institutional doctrine, but you can manipulate monitoring density (structure work so people observe each other more), sanction salience (make consequences swift and visible), and enforcement consistency (detect violations without necessarily punishing them teaches that norms aren’t real).

Importantly, this mechanism tightens adherence to whatever norms the monitoring network enforces. If institutional oversight is weak but unit-level monitoring is strong, units can develop tight cultures around wrong norms. The Australian SAS case showed this: systematic violations persisted because monitoring collapsed at institutional level while remaining tight within units around deviant practices.

Making cultural norms visible helps too. In the British Army, there are the Values and the Standards. The values any soldier knows—Courage, Discipline, Respect for others, Integrity, and so on. The standards aren’t so commonly known: Lawful, Appropriate, Totally Professional. Values are extremely hard to define in any organisation.3 What is courage, for example? I could point out recklessness and cowardice, but I’d be hard pressed to tell you how you could tell apart an act of courage from its two extremes.

The standards are the British Army’s attempt to help—if a bold act is Lawful, Appropriate, and Professional, then it’s probably Courageous and not Reckless or Cowardly. Making norms visible means the monitoring network knows what to enforce.

Outro

The ETHIC stack isn’t supposed to be a comprehensive solution to ethical education. It’s an illustration. A demonstration of what’s missing from models of ethical behaviour, and a framework for thinking about how to improve them. Ethics is fundamentally prescriptive, after all—it tells people what they should be doing. To make it practical, we must add in a science of behaviour—telling people how they can go about doing it.

The template for these is the mechanism: entities (ingredients) that do things (activities) and are related to one another in producing behaviour (organisations). Whether you choose the mechanisms described by the ETHIC stack, or some other thing, a collection of moral mechanisms gives students the levers to turn ethical education into ethical action. The ETHIC stack, for example, illustrates how ethics can be operationalised at five, interconnected, layers:

- The Early, emotional circuitry: our ‘pattern detector’ which tags patterns of stimuli with a valence—a basic sense of goodness or badness—and pumps enough energy into the system to urge us to approach the good and avoid the bad. We call these moral intuitions and they colour all moral decision-making. To improve the intuitions our pattern detector produces, we have to train it—make it more sensitive to moral content by talking through examples of ethical behaviour.

- The Thought-level schemas: the ‘lazy controller’ who responds to cognitive conflict, like a ‘right vs right’ decision, by engaging or disengaging with moral content—whatever is easier, and will allow it to go back to sleep faster. To improve it, we have to be sensitive enough to moral content to generate the conflict in the first place, and practice moral engagement so that it becomes easier than disengaging.

- The Habitat (immediate situation), named just to make the acronym stick, is an ‘affordance auction’—a way of considering how the environment ‘affords’ us certain opportunities to act, and makes some opportunities more obvious than others. Thinking about what makes some actions more salient and useful, while minimising the costs, is a way of making the situation into an asset, rather than a liability, but it also shows us that once we’re in a situation, it’s often too late.

- The In-group dynamics is the most tractable level. Our ‘prestige engine’ steers us to conform to some social norms over others—the ones that provide social capital to do so. The engine doesn’t work, though, without other similar groups to make us want to demonstrate our membership, nor does it work without representatives of the group to make us feel observed. Manipulating any of these elements can drive us towards ethical and away from unethical behaviour.

- Lastly, the Cultural scaffolding—the ‘enforcement infrastructure’ through which norms become behaviourally relevant. Not just the content of values an organisation expresses, but the monitoring networks (who observes whom) and sanction systems (how consistently violations trigger consequences) that make those values constraining. Threat environments create coordination pressure, personnel density amplifies monitoring, and enforcement consistency determines whether norms are real or just words. Manipulating monitoring density, sanction salience, and enforcement level (institutional vs unit) offers more leverage than initially obvious.

More importantly, the C-level describes where ethical norms are injected into the ETHIC stack, which would otherwise merely be an incomplete account of all behaviour rather than an illustration of ethical behaviour.

If the mechanisms I picked don’t tickle your fancy, then my paper describes handfuls more, and if the levels of the ETHIC stack aren’t the levels that work for you, then my paper describes other organisations too. The point is merely that ethics can be more than an intellectual exercise.

I think I’m onto something. You can let me know.

See also me applying ETHIC to the military decision-making ‘S-CALM’ model.

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.