It's not 'just' a placebo

December 28, 2021

Excerpt: Would you be surprised to learn that we still don’t really know how paratetamol works? Or general anaesthetic? We accept all sorts of mystical effects from our drugs without particularly understanding them—just trusting our doctors. What we’re doing here is simply surrendering to experts in a certain kind of knowledge production. The question is, why do we do this with drugs, but not with other things? Why do we handwave away the benefits of off-piste and esoteric therapies when they work and we don’t know how, but we don’t treat drugs the same way?

Ideology

The phrase “it’s ‘just’ a placebo effect” is used to wave away inconvenient findings that some alternative therapies work, because we don’t know how they work. But many of us frankly don’t know how any medicine works and this blind one-directional faith is often misguided.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

Would you be surprised to learn that we still don’t really know how paratetamol works? What about penicillin?

Both have been used for over 100 years to treat illness. Both are household names. The kind of drug Dr. Cox would have us throw down our throats at the first sign of illness.1 And yet both have yet to give up all their secrets to us.

We take them with no question, because we know they work, but never do we think to ask why they work. Isn’t that curious?

If we had asked, we would be left with no answer. And still, knowing this—knowing that we don’t know—will it stop us from taking these things? I suspect not. This, too, is curious.

Indeed, as we’ll see, this circumstance is more curious than one might assume on the surface.

The dual mysteries of drug action and discovery

That this odd fact is true for some of our most recognisable drugs means that it is perhaps more true of less recognisable drugs. For example, lithium is a popular treatment for depressive and manic symptoms, and yet we still don’t really know why it’s such a good mood stabiliser. We also don’t really understand how general anaesthetics work. Quite recently, for example, we discovered that the ingredient in a set of anti-cancer drugs we thought was killing cancer, actually wasn’t killing cancer at all—something else (still unknown) in the cocktail is the true culprit.

Even when we do know how a drug’s action targets the illness we’re interested in, it’s often only after some period, sometimes decades, of knowing only that it works and not yet knowing why. As this study points out, despite the incredible resources invested in trying to find drugs based on theories of why they might work, the vast majority of drugs are discovered instead by showering cells with random chemicals to see which chemicals have a beneficial effect.

All this is not to mention the fact that we regularly take, or are prescribed drugs that everyone knows won’t work as advertised. Everyone except, of course, for us.

Take cough medicine. Any number of sites will point out that, e.g.:

Dr Tim Ballard, vice chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, said: “The medical evidence behind cough medicines is weak and there is no evidence to say that they will reduce the duration of illnesses - as such, GPs are unlikely to prescribe them.”

or:

“We’ve never had good evidence that cough suppressants and expectorants help with cough,” says Norman Edelman, MD, senior scientific advisor at the American Lung Association.

This is not for lack of trying to find evidence either. Fact is, no matter how hard you look, the honey you use to keep the cough medicine down seems like it’s doing a better job than the medicine itself.

It’s also worth pointing to the lazy overprescription of antibiotics and opioids, each of which has unnecessarily led to their respective crises and are only now, at the point of said crises, receiving widespread attention.

The difficulty is not merely laziness of course, or negligence. To be honest, it’s actually very difficult to determine just what, exactly, a ’working drug’ is.

Does a drug work if only 20% or 30% of people improve? What if 10% improve 100%, but the rest don’t improve at all? Do these ‘work’ or ‘not work’?

This kind of question might appear odd—surely we would have worked this kind of thing out. And yet governmental drug administrations are regularly forced to make these kinds of decisions up on the spot. It’s only that we never hear about, or pay attention to, the furore that follows in medical circles.

And why should we? We’re not experts. Medics are. Let them furorate and meanwhile, let us take drugs and get better. Because of the drugs, or in spite of them.

This is not an unreasonable position to hold. We could probably be a little more skeptical of the pharmacological model in general, but we certainly can’t be expected to do our doctors’ job for them.

But it is here that the point of curiosity in our medical orientation is most stark.

We accept all sorts of mystical effects from our drugs without understanding them. How do they fix the thing? Why do they simultaneously fix the problem we have, but at the risk of inducing alarming side effects that seem like non-sequiturs—common pain medication and burn-like blisters for example, or anti-depressants and nose bleeds?

What we’re doing here is simply surrendering to experts in a certain kind of knowledge production.

The question is, why do we do this with drugs, but not with other things?

Getting to the point

Let me make the point clear with the most stark comparison.

It is essentially well-known that, on average, anti-depressant drugs work no better than placebos in the treatment of depression.

Dive into the details and you find, of course, that some forms of depression respond better to drugs than others, or some drugs work better than others. But though the proportions may be comprised of different people, roughly the same proportion of people that respond to drugs respond to something that is, by design, the exact opposite of drugs:

A placebo … is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value.

And although this is the most striking case, it’s hardly an isolated one (as we will discover). The placebo effect is, frankly, stunningly effective. And so, we should reword my earlier question to be more specific.

Why is it that, when someone undergoes a course of alternative therapy, and it works, our collective response is that it’s just a placebo?

Why do we handwave away the benefits of off-piste and esoteric therapies like reiki, chiropractic, hypnosis, homeopathy, and herbalism with this odd little phrase?

It’s clearly intended to be condescending. The inclusion of that heavily weighted ‘just’ makes that abundantly clear. It’s meant to be synonymous with a phrase like ‘it’s all in your head’.

I suggest the closest meaning to that implied is that whatever benefit derived was somehow accidental, not incidental. That the treatment worked, not because of the treatment, but in spite of it.

Just like drugs.

And so, perhaps now, my point is clear. Let me proceed to beat it to death.

Placebos that work

Let us move away from the medical term for placebo, and adopt the common use. The medical term means ‘something that is designed to have no therapeutic value’. The common use is, as I said, something closer to ‘something that is all in your head’.

This isn’t, in fact, too far from the original definition of the word. Placebo, derived from the latin for ‘I will please’, was originally used to describe medicine designed more to please the patient than to benefit them.

With this little transformation, we can attack this odd little human foible of ours more directly. We can address, specifically, that something ‘merely’ designed to please, or something that targets our psyche over our molecules is something we should be comfortable handwaving away. That our pleasure is somehow different to our benefit.

Let us also, for now, operate under the strictest constraints, in which we’re not allowed to invoke mechanisms outside the scientific canon like healing energy fields or molecular memories. Under these constraints, the effects of the placebo must be limited to whatever tools our bodies have on hand to fix the problem and, miraculous cases aside, are usually limited to addressing only certain kinds of symptoms. On this view, a placebo couldn’t cure diabetes, but merely alleviate some of the outcomes. It couldn’t eliminate multiple-sclerosis, but simply make it less visible in our lives.

With these in mind, let’s explore these ‘mere’ placebos.

Back to antidepressants

The first example is easiest. We have already noted that a placebo has, on average, roughly equivalent performance to antidepressants. This is such a striking result that some suggest the placebo effect is accounting for some proportion of the improvement in even those treated with the drugs.

Under our strict constraints, this is entirely plausible. A placebo, limited only to addressing symptoms, would be wonderfully placed to treat many kinds of psychiatric illness. The problem with most mood disorders is precisely the symptoms. The so-called ‘chemical imbalance’ theory is largely under question, mostly because we have no idea what a chemical imbalance would even look like. To quote myself:

serotonin is known as the ‘happiness molecule’. We know it has a relationship to mood. Interesting evidence suggests this is so. For example, we think that the despondent ‘come down’ after taking drugs like MDMA is related to a depletion of serotonin in the brain.

But if you just flood the brain of a depressed person with serotonin, they don’t get happier. The anti-depressant that does this only improves symptoms for something like a third of people. A similar number to simply providing a placebo pill instead. More interestingly, people taking these drugs are more likely to try and kill themselves.

We shouldn’t draw too many conclusions from this, because many other factors are at play there. But it certainly makes clear that the claim that we know what a chemical imbalance looks like, or how to fix it, would be overstating the case.

Rather, mood disorders are often characterised as disorders of distress—a diagnosis that asks whether the person is suffering unduly from their symptoms rather than if anything is physically untoward. The subjective point at which reasonable responses to a stressful environment have become something they feel they can no longer manage.

If a placebo is the thing that alleviates their suffering, or helps them manage their symptoms better, then the mood disorder is no longer so disordered. The fact that the placebo was in their heads would be precisely the reason it would be so effective.

Moving to the tangible

But even if it were some chemical imbalance, it wouldn’t seem particularly strange to me to learn that a placebo could address this too. Things that are ‘all in our heads’ can have extraordinary impacts on the more tangible parts of our heads, and indeed the rest of our bodies.

For example, it is uncontroversial that meditation therapies like mindfulness-based stress reduction quite literally induce changes in the brain. Meditation is, certainly, all in the head. That’s the point. Is meditation a placebo? Perhaps not according to the medical term of art. It is designed to help. And of course, learning how to reflect in new ways upon our thoughts is going to encourage the brain to start operating in a different way, with corresponding neural growth. But this fact certainly doesn’t gel very nicely with the common application of the term. Where does being ‘in the head’ stop being illegitimate, and start being the exact thing that we’re looking for?

Meditation, more controversially, appears to have some relationship with the immune system—speeding recovery or slowing decline in auto-immune disease, or generally boosting the immune response.

Chronic stress, both psychological and physical, is well-known to influence our immune response, so perhaps it’s no surprise that a technique derived to address stress would benefit our immune systems. One is left to wonder, if the psychological action of stress reduction comes from a weeks-long course of cognitive behavioural therapy, weeks-long course of meditation therapy, weeks of reiki sessions, or weeks of daily homeopathic pills, why do we see only some of these as legitimate solutions?

These kinds of immune changes don’t always need to last the length that the placebo is in play, either. A discipline called Placebo Controlled Dose Reduction is struggling into existence, squeezed between pharmaceutical interests and academic disdain. It has shown great promise in conditioning the immune system to maintain some of the gains made while on pharmaceutical drugs during those times the drugs aren’t present. They do this by associating those gains with a placebo. It is the classic psychological concept of classical conditioning, extended to medicine. The placebo acts as a signal for the body to try to arrange itself into a better immunological shape it learned while on drugs, reducing the need for quite so many of those drugs.

A similar thing seems to be true of hypnosis. Hypnosis is subject to a great number of myths. But at it’s core, hypnosis appears to move us from our normal state of consciousness2 with our normal capacities for controlling our body, into some more focused kind of state with less-normal capacities for controlling our bodies. In this more focused state, we appear to be able to influence typically unconscious processes.3 And, when we return, these influences sometimes seem to stick around, sometimes for years.

And these kinds of mentally induced changes don’t merely happen at the levels of our physical machinery. They can happen at the level of our code—our DNA. The phenomenon of social rejection is not a placebo, by anyone’s definition. But it is certainly ‘all in our heads’. It’s necessarily cognitive, because a social rejection needs to be interpreted to be anything at all. And social rejections are known to make changes to your genes—changes that make you less resistant to viruses and more likely to have inflammatory responses within 40 minutes of the rejection event. Evidence that such genetic changes happen due to events in our lives is growing rapidly, and there seems no reason why a placebo couldn’t play on this field as well.

Each of these things, have at times, been called a placebo or at a minimum represent the kinds of tangible effects we might expect of a placebo. And each have been chosen to emphasise how profound such changes can be—far beyond the very cautious conclusions offered by the general medical community on the topic in the face of a stunning array of apparently genuine effects.45

The action of the mind is as potent as the action of a drug

But, for reasons we have gone over many times before, we must recognise the limitations of the scientific belief system:

Scientists are often scientists only when it is necessary, or convenient. The rest of the time they are subject to the same frail processes of thought that all humans suffer.

The scientific bias is … often a lazy one. No evidence might indicate evidence in the same breath as it indicates that no one has looked for any. A ‘rational’ common sense that ignores things because it can’t be bothered to figure out why those things might be or is too much indulged in the destruction of things that can’t be.

It is an ideology like any other, making some chaos into order, but leaving some order unexaminined. It is up to us to rescue these things from the void.

Or as Daniel Moerman puts it, less kindly, and more specifically for the placebo effect:

The one thing that seems absolutely essential [in scientifically reviewing the placebo effect] is that “No Thinking Is Allowed.” Rather … the most improbable and unlikely contradictions are the ones that work best, to be most congenial to placebo reviewers.

The fact of the matter is that we often use the placebo as a convenient catch-all to deride those things we don’t understand, or have been told that we don’t understand. This in comparison to the drugs we have been conditioned to accept without questions. And this because the medical community views the capacity of the mind to be as intangible as the average person believes it to be. It should not escape us that doctors are people too.

As such, anything which appeals to the mind as a solution becomes something neglected or maligned. First by doctors, and then by us, those who have surrendered to their method of knowledge production.

The medical method of knowledge production isn’t simply subject to the quirks of scientific laziness, it is subject to an obsession with the idea that molecules and biochemical pathways might have more tractable qualities. Indeed, one might argue that the only reason the placebo effect holds any attention at all is because we are only now stumbling across these features in those effects too.

But this distinction, between the mental aspects of the body and the physical ones, is an entirely illusory one. There is no meaningful way of characterising the mind without a body, and no meaningful characterisation of a body without a mind. At least, not one which is alive.

Our mind, most easily but hardly exclusively, represented by the brain, is the mediator of our perceptions and actions. From hormones to behaviour it is responsible for adapting our responses to the world around us. And to do that, it uses our memories of the past and anticipations of the future to decide how we should allocate our mental and physical resources.

When it comes to placebo effects, both those we know, and those we have yet to explain, our laziness and our obsession has led us to neglect the experiences of people.

And in many cases, it is those experiences that count the most.

It is not the therapy, but the meaning that matters

In his delightful editorial in the Journal Pain Practice, Daniel Moerman identifies clearly the thing that seems to make most placebos work:

The interesting part is the response to the meaning of the encounter … So, four placebo tablets a day have been shown to be more effective than two placebo tablets a day. Injections of saline solution have been shown to be more effective than inert tablets … Inert blue tablets make better sleeping pills than inert red tablets … Although less common, there are a number of studies that have shown that sham surgery is a highly effective treatment for everything, from bad knees to angina, from low back pain to transmyocardial laser revascularization. One delightful study randomly divided pace-maker recipients into two groups; in only one group were the pacemakers turned on. All patients were much better than baseline, by very nearly the same amount, after eight weeks …

One can go on and on; but in all these cases, it is clear that the “placebo” has nothing to do with what is happening. It is what the placebo means that makes a difference.

Things that provide the person an impression of a more potent medicine have a more potent effect. It means more, so it does more.

Elsewhere, Moerman comments on one review paper on antidepressants which demonstrates that from the 1970s to the early 2000s, the effectiveness of placebos in treating depression has increased alongside the effectiveness of antidepressants. Moerman suspects that awareness of the effectiveness of antidepressents is having an effect on the meaning that this kind of treatment might hold.

The point is that the expectation of what the treatment can do for us is the powerful agent of change in many of these placebo effects.

And if that’s true, then our expectations of what the meaning should be become the important variable to focus on.

For example, if we recall that, under our strictest constraints, the placebo must use whatever tools our bodies have on hand and address only those symptoms that would not represent miraculous cures (like the recovery of atrophied brain in dementias or the lack of some functioning organ), then we recognise that placebos are best placed to address cognitive symptoms. Anxiety, stress, sadness, and the suffering from pain—all symptoms that have cognitive origins, all can be addressed with cognitive tools. Of which, our expectations of what should be are important mediators of what we perceive.

With that in mind, and knowing that all of these things are commonly produced by any kind of illness at all, it might not surprise us to learn that one important factor in the placebo effect is a caring interaction with the therapist delivering the treatment.

When a placebo is delivered by a doctor with an explanation, it is more powerful then when it is prescribed with no interaction. When senior scholars in the domain of psychosomatic illness are interviewed the importance of the therapeutic relationship comes up repeatedly. One explanation for why so-called ‘honest’ placebos work—in which the patient is told the medication is inert—is thought to hinge on the interaction between the researchers and the patients. In her book, Cure, Jo Marchant quotes key placebo researcher Ted Kaptchuk as noting that placebos might often work because the patients are taking “home the care, the concern” of the therapist. In his recent article with co-author John Skoyles, Nicholas Humphrey reiterates a point he regularly makes in print, that the “that tender loving care” that is provided in a healthcare situation might “call off pain”—it is the signal that the pain is no longer needed.

And all of this, we did not need senior medical researchers to tell us. This we can observe by merely kissing the injury of our children and watching as their tears become smiles.

We expect our ailment to improve from the attention, and so it does. It is the meaning that matters.

Optimising for meaning

This last point brings us roughly back to the start:

We accept all sorts of mystical effects from our drugs without understanding them. How do they fix the thing? Why do they simultaneously fix the problem we have, but at the risk of inducing alarming side effects that seem like non-sequiturs …

What we’re doing here is simply surrendering to experts in a certain kind of knowledge production.

The question is, why do we do this with drugs, but not with other things?

The answer is similar to the answer to our most constrained explanation of the placebo effect. It is the meaning that matters, and we have been taught that drugs are meaningful and other things are not.

As I detail elsewhere:

The scientific emphasis of secular western culture since at least the enlightment introduces a terribly high barrier to entry on certain kinds of knowledge.

Anything that sits outside the accepted scientific milieu is prone to intense skepticism. Homeopathy, astrology, herbalism, crystal healing, chiropractic therapy, the list goes on …

But all of these phenomena are popular because people claim that they work … for them, the scientific method has failed these phenomena, but that does not mean they are illegitimate. This opinion is often worth a more tender examination.

In that article, I explain that, even based on principles of empiricism, this is a truism. In this article, we are motivated in a slightly different manner.

If our placebo effects are about the meaning that a treatment can provide, then many of the alternative therapies the medical milieu dismiss might be even the most appropriate treatment for certain kinds of illness. With sessions that stretch over hours and built around the care that senior medical researchers value so highly, they are far more prepared to deliver meaning than the prescription of a drug.

This kind of benefit might be far more important than we’re comfortable. Consider, what even are many illnesses except the negative feelings associated with them? When the pain incurred becomes suffering? And if we mitigate pain or these other cognitive effects, how many illnessess would be for intents and purposes cured?

And indeed, if the key idea that arises from our exploration of these effects in cases such as these is that it’s often our expectation that a treatment will work, rather than the treatment itself, then entirely new worlds of therapy become open to us to treat certain kinds of problems.

Not merely popular ones like Traditional Chinese Medicine or Ayurveda, but perhaps even spiritual ones that claim no particular medical relationship at all. Spiritual practice places meaning at its very core—finding purpose in ritual is a key feature. It is no coincidence that the shamans of animist spiritualities were called ‘medicine’ men and women, and responsible for the healing of their people.

Even the research agrees. The rituals with which we surround our drug-taking are important mediators of the placebo effect. A sham surgery is more potent than an injection, which is more potent than a pill. Some researchers suggest we lean into that fact—taking medication at a special time or place, or accompanying it with a prayer or meditation. Even in more controlled medical trials, researchers are trialling things like neon green drinks with strong flavours to maximise the effect of their placebo work.

If anything that helps to give the impression a medicine is more powerful makes that medicine more potent, why not embrace the expectations that our ancestors did and many cultures still do—that ritual is a vehicle for healing? Maybe not instead of drugs we know to work, but there seems little harm in trying alongside.

To conclude: when mechanisms matter

This last section might bring us some discomfort. An invitation to step entirely outside of the scientific milieu, or at least step towards the fringes.

But we should consider why these things sit outside the scientific milieu at all. Alternative medicines, and the power of spiritual healing, are dismissed because the mechanisms that they purport don’t gel with the evidence-based approach.

We might not know why paracetamol alleviates pain, but we can at least wave our hands toward metabolites and the inhibition of biochemical pathways.

We don’t really know why reiki makes people feel better, and waving at healing energy fields doesn’t really make some of us feel better about the whole enterprise.

But, as I’ve pointed out before, this is a distraction. It’s a thought-stopping way of thinking that is lazy at best, and negligent at worst. Just here, in this article, we’ve explored many mechanisms by which such things might have an effect.

But an even more fundamental question that is raised in our exploration is, what actually matters here? Do we always require a mechanism?

For some people, it might be the care that matters. For others, merely the expectations that a deceptive but inert capsule provides. For others still, it might be the ritual that emphasises the power of the thing.

And exploring all these various psychic mechanisms seems important. Perhaps we might gain some marginal boost in effectiveness. Certainly we might identify when these practices become toxic. But, the human system is so absurdly complex that we still only vaguely understand something as fundamental as nutrition—we can’t even agree on what nutrients we need:

The list of nutrients that people are known to require is, in the words of Marion Nestle, “almost certainly incomplete”.

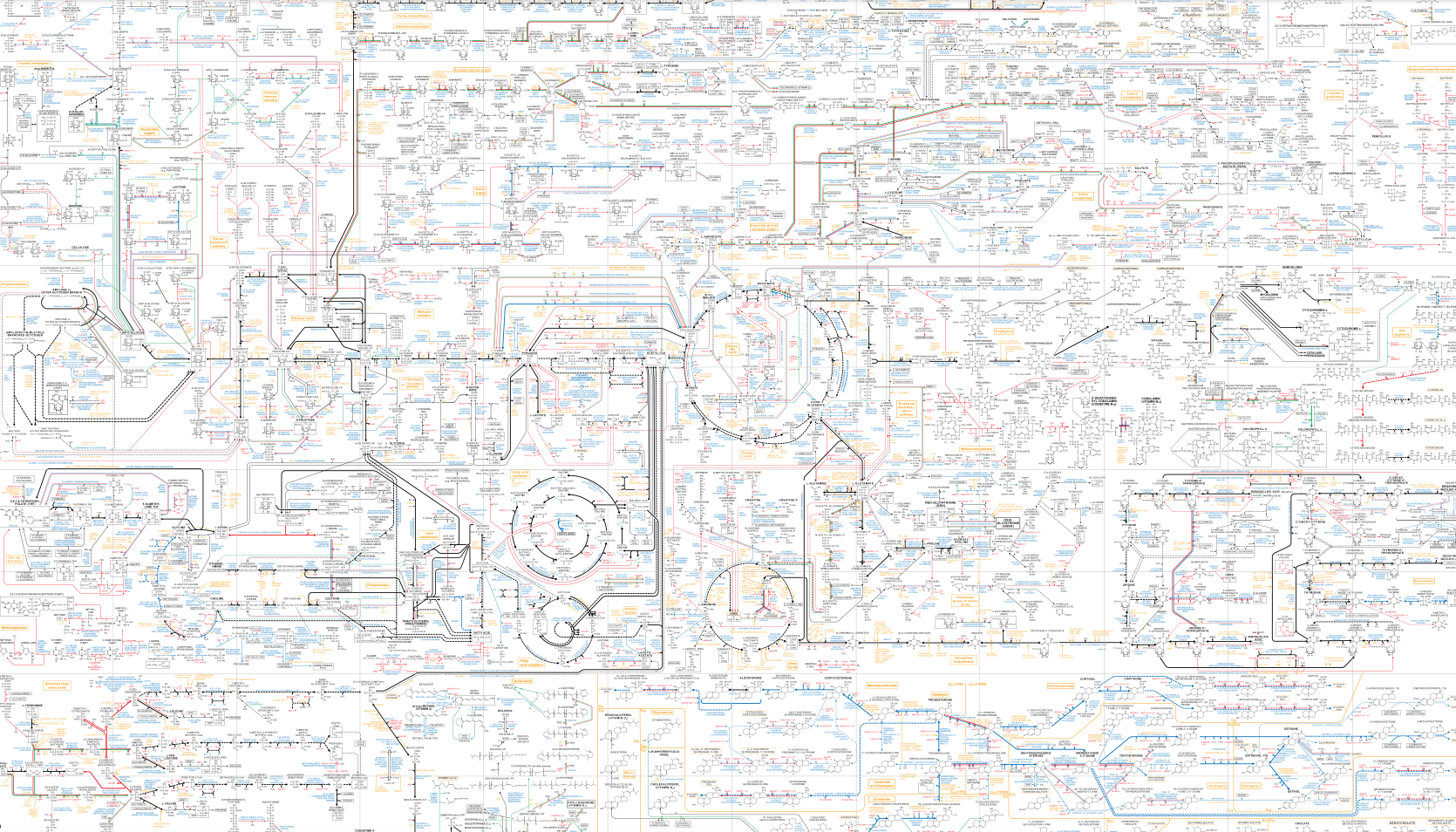

Which makes sense given that this is only a fragment of what I could screenshot of a map of the human metabolic pathways that we are aware of:

Like the subway map from hell.

Like the subway map from hell.

Given we haven’t even worked out how food works yet, precisely how beneficial this kind of research will be is a question with dubious hope of being answered soon. That’s even assuming that researchers can even motivate themselves to address the substantial social and financial obstacles that surround such research.

Similarly, we might continue to call these things by more mystical names, and try to pin things down this way. Appealing to healing energies and divine intervention rather than the equally baffling biochemical interactions is not so bizarre. As above, we are constantly reminded of just how little we know about the world we inhabit. It’s not like the medical model has all the answers, even for the people who’s job it is to know these things.

Under the medical model, with medical schooling, or outside of it with the knowledge the average person has, we’re often forced to appeal to things we don’t, or maybe can’t know—forces beyond our expectations or influences that lie far beyond our maps. What harm is there in giving them mystical names?

Because, mystical names or more prosaic ones, these things don’t matter to people. Whether it’s the mysterious actions of well-known drugs, or the mysterious action of some mental phenomenon, or something else entirely, I would suggest that people don’t particularly care so long as it heals them.

We are almost entirely at the mercy of the knowledge systems of our experts. The thing that really matters is that we are surrendering to knowledge that is not like our knowledge when that knowledge works for us. Be it the doctors’ experiences in the hospital room and their faith in the mind-boggling number of facts memorised in medical school, or the herbalist’s experience with a herbal tincture and their knowledge that their ancestor and their ancestor’s ancestor used this same remedy cure that symptom of illness. In cases like these, how important is the theory relative to the outcome?

In her book Cure, Marchant concludes “rather than putting our faith in mystical rituals and practices… It’s not necessarily the potions or needles or hand waving that make you feel better”.

But for all intents and purposes, it is. It is exactly this, that she spent 12 chapters detailing. It is exactly this that I just spent 5,000 words detailing.

Marchant goes on to say that we should “live in tune with our bodies in a way that is based on evidence, not delusion” as if these are the only options available to us, but she spent the entire book rigorously demonstrating that this is, in fact, as absurd a distinction as the mind-body distinction her entire book, attempted to eliminate.

The evidence hints that there are a range of such extraordinary effects, and sometimes points us in certain directions, but reliably fails to capture them in their entirety because scientific evidence can only take us so far. A delusional belief in the purity of evidence-based medicine would have us jumping out of planes without parachutes because there’s no evidence to support its benefit. Or less trivially, still labouring under the academic dogma that the immune system and nervous sytem are completely seperate, and stress doesn’t influence our inflammatory problems—something that has only started to be addressed in the last couple of decades.

Similarly, while many alternative therapies veer into deluded territory, that does not mean that behind those delusions are things that often work, and evidence is often the thing that points us in the right direction. While many chiropractitioners are still rooted in the therapy’s past as a mystical healing technique6 and worry about occult concepts like innate intelligence, that doesn’t mean that musculo-skeletal alignment doesn’t improve certain kinds of mechanical problems. The very fact that many people don’t know that chiropractic is still struggling with its extremely unscientific core is telling in and of itself.

In these cases, it’s neither precisely the scientific evidence nor delusion. Somewhere in the valley between the two, there was a series of outcomes. Real experiences that helped people. It’s these experiences that matter—what these things mean for them.

When we don’t look closely enough, we leave feeling cheated, or worse, feeling more ill then when we started.

But when we look too closely, we are liable to look past the important fact—that the thing works.

We don’t do it for paracetamol, so why do it for the placebo?7

Special thanks to Jo Marchant's book Cure: A journey into the science of mind over body for sparking this train of thought and inroads to the research. And to Laura Marsh for lending it to me.

Noting, of course, that this is a shaky concept at best ↩

Another shaky concept ↩

For this, a well written overview exists in chapter 2 of Jo Marchant’s book Cure. See if you can read that chapter in the free preview linked there. ↩

It is also worth noting that some of the most profound effects of this kind of placebo effect come from so-called ‘nocebos’. Derived from the latin for ‘I will harm’, nocebo effects are those that come from an expectation of harm rather than a harm physically conveyed by a treatment. Like experiencing nausea from a sugar pill, when told nausea is a side-effect of the drug one thought one was taking. In this vein, we might see the full complement of drug overdose symptoms in a man who O.D.ed on placebo pills. After being told as such, the symptoms disappeared. Or consider the incredible list of mass psychogenic illness or ‘mass hysteria’, in which entire towns can demonstrate extraordinary physical symptoms of illness when under the impression, for example, they have been gassed or poisoned. Or, perhaps engage in more atrocious behaviour like that seen in various witch trials, convinced that the most cartoonish versions of magic are afoot all around them. Indeed, sometime placebos might merely be the removal of such nocebo effects. An interesting twist indeed. ↩

Causing so much controversy there’s an entire seperate Wikipedia page on it. ↩

I don’t have anywhere to put this, and I thought I would add it to the conclusion here, but I rather like this conclusion, so I’ll footnote it. It’s a quote. Who knows from who. It goes: “Witches call it spells. Christians call it prayer. Spiritualists call it manifestation. Atheists call it the placebo effect. Scientists call it quantum physics. No one denies its existence.” I’m not super sure about that quantum physics bit, but I like it. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.