A Science of Discontent

October 31, 2022

Excerpt: The popular conception of stress is an enormous obstacle to growth and performance. Funnily enough, this is most stark in environments where performance is most important. It is almost the exact opposite of the eloquent version of ‘adversity builds character’ quoted above, which is much closer to the truth though still not quite correct.

Ideology

We regularly create ‘psychic predators’, choosing to concentrate on the uncontrollability of events or concentrating on events we can’t control. A far better way of approaching this is to exercise our ‘psychic muscles’.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

There should be a science of discontent. People need hard times and oppression to develop psychic muscles.

Princess Irulan, Collected Sayings of Muad’Dib

The popular conception of stress is an enormous obstacle to growth and performance. Funnily enough, this is most stark in environments where performance is most important. It is almost the exact opposite of the eloquent version of ‘adversity builds character’ quoted above, which is much closer to the truth though still not quite correct.

This Harvard Business Review article exploring Amy Edmondson’s research on ‘psychological safety’ is a fantastic example:1

“The brain processes a provocation by a boss, competitive coworker, or dismissive subordinate as a life-or-death threat. The amygdala, the alarm bell in the brain, ignites the fight-or-flight response, hijacking higher brain centers. This “act first, think later” brain structure shuts down perspective and analytical reasoning. Quite literally, just when we need it most, we lose our minds. While that fight-or-flight reaction may save us in life-or-death situations, it handicaps the strategic thinking needed in today’s workplace.”

On reading this, what sane manager would be enthusiastic about ‘provoking’ her employees? What colleague would dare seek to compete?

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has been most prominant in illustrating the impact these concerns have had on performance in the academic world:

In the twentieth century, the word “safety” generally meant physical safety … But gradually, in the twenty-first century, on some college campuses, the meaning of “safety” underwent a process of “concept creep” and expanded to include “emotional safety.”… depriv[ing] young people of the experiences that [they] need, thereby making them more fragile, anxious, and prone to seeing themselves as victims.

These same concerns have similarly plagued the business world since the widespread adoption of Daniel Goleman’s concept of ‘amygdala hijack’ in the mid-90’s.2

Unfortunately, the popular conception of stress is usually quite incorrect. The human stress response is possibly the single most valuable piece of biological technology available to us.

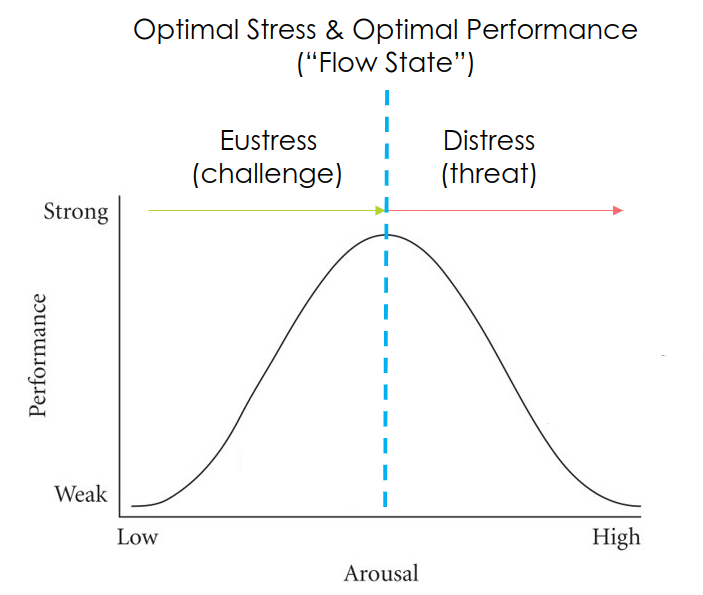

Without re-hashing the article linked there, very simply, stress or ‘physical arousal’ is the energising force that helps us achieve the effort required to meet the task at hand. It motivates us to perform and recruits the physical and mental resources required to perform. Importantly, optimal stress is required for optimal performance. This is known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law.

The brain certainly does not respond to any kind of stress with the kind of ’hyperarousal’ elicited by life-or-death situations. Funnily enough, for most people, only life-or-death situations tend to do that.

As stress increases, so does performance. This is Eustress. As stress goes up

higher, eventually performance decreases. This is Distress. Source: Wikipedia

with my crude editing on top.

As stress increases, so does performance. This is Eustress. As stress goes up

higher, eventually performance decreases. This is Distress. Source: Wikipedia

with my crude editing on top.

A more useful way to think about stress is to distinguish between eustress and distress. Eustress is the kind of stress we feel when we are faced with a challenge we think we can meet. It motivates us to engage and succeed. When the challenge and our capabilities are particularly well-matched we enter what is known as a flow state—a very pleasurable experience thought to characterise the height of performance.

Distress is the kind of stress we feel when we are faced with a threat: a challenge we are concerned we can’t overcome. This kind of stress motivates us to withdraw and defend.

Many pop-psychology and business writers recognise the difference between these two things (e.g. broaden-and-build mode; learning-vs-protection; and even the aforementioned ‘limbic/amygdala hijack’ which, though anatomically very incorrect, is kind-of superficially informative). However, by commonly tangling the kind of stress we feel when our survival is threatened with the stress we require to engage in a task leads us to more frequently pose all stressors as threats and not challenges.

Psychic predators (redux)

I wrote a short piece not long ago about psychic predators. Specifically about the phenomenon of Donald Trump. I am suspicious of how interesting everyone finds him. Trump is fairly obviously a symptom of some underlying problem of representation. The visible emblem of the USA’s particular brand of elite-populace disconnect. An embodiment of the successful prophet—an enthusiastically valueless face upon which marginalised people can lay their preferred ideologies. It would seem that that is what is interesting. And in a sense, it is—particularly now, with this fun new QAnon layer. But in another sense what is interesting about him is, I guess, his moods? And eating habits? And hands and skin tone and capacity for schoolyard insults?

Why all these articles about how awful and weird he is? Is that helping solve something (outside feeding the usual media interests)? Several years into peak-Trump it certainly seems not. Many have noticed this too, going on to suggest there is something unique about Trump—some brilliant strategy to co-opt the media cycle. But frankly, I don’t buy it. He didn’t master the collective imagination, we placed him in there. We looked at Trump and chose him as a psychic predator. And there he remains.

This emphasis on stressors as threats does something similar. It imbues challenge with danger, and thus conjures psychic predators. The important distinction here is that psychic predators are predators we choose.

Let me make it clearer with another, more obvious example. At the time of writing, Russia and Ukraine are at war. People are very concerned about this.3 One acquaintance, in the UK, shared with me their levels of stress around the issue. They were glued to the coverage, regularly thinking about it, and indeed found themselves up at nights, unable to sleep because of the war. I expressed my sympathy, of course, and delicately inquired if they had family or friends in Ukraine. They did not. I wondered if they were concerned about the conflict spilling over and affecting us here. They were not. I wondered if they had found any strategies to help them calm down with regard to the war in Yemen or the war in Syria. They were actually unaware that these conflicts were ongoing. I wondered, this time silently, just what it was about the war in Ukraine in particular that had them so exercised.

Around the same time, a different and much closer acquaintance, in Australia now, called me in a panic to see whether I could get my hands on military hardware from my ‘military contacts’ so we could, I guess, mail it to the Ukrainians? This conversation was a rather short one (’… are you out of your fucking mind?’), but illuminating—in memory, this person had never talked about a country further away than Thailand before so this was quite the jump in geopolitical interest. I asked similar questions of them as I did of my other acquaintance. They appeared similarly bereft of motivation to care about this war in particular. Since this acquaintance was closer, I pushed a littler harder and asked the Australian about the Australian contribution to the war in Afghanistan, the source of the first Australian combat deaths since Vietnam, peaking just about the time I signed up for the Australian Army—something that you’d think they might have had some misgivings about at the time. It had never occurred to them to think of any risks to me. I wondered, less sympathetically now, whether they were concerned that I’d be recalled to the army if the tensions between China and the US continued escalating. They were similarly surprised to learn that this might be of interest to them.

For both acquaintances, the war in Ukraine was far more important to them than any other current conflicts, and yet their interest was purely abstract and unaccompanied by any personal connection. Perhaps I just have shitty acquaintances, but I don’t think so. I don’t think there was some ethical decision about what wars to pay attention going on here. I think they reflect the general level of concernedness about recent wars. Some level of this is media attention. But a large contribution comes from what we are choosing to pay attention to. The war in Ukraine has become a psychic predator. The other wars, not so much. Not so lucky for the Yemenis.

Back to the point, the popular conception of all stress as life-or-death stress means that this is how we will choose—by default—to pay attention to stressors. This is the concern of people like Jonathan Haidt and Stephen Pinker. It makes stressors into psychic predators.

This is bad, as we have said, because stressors are required for performance. But that is covered elsewhere. Here I want to focus on how stress is also a critical tool for growth.

Psychic muscles

You’ve probably heard the adage “adversity makes us stronger”, or “it’s character building”. A better quote comes from Frank Herbert’s Dune:

There should be a science of discontent. People need hard times and oppression to develop psychic muscles.

Princess Irulan, Collected Sayings of Muad’Dib

Fortunately, the science of discontent is here now, and it tells us that this is not quite right, but it’s very close.

To be clear, everyone’s stress curve will look a little different. Challenges for some are threats to others. Nowhere did I learn this better than working as a Crisis Counsellor. Ostensibly, our role was to prevent suicide, but there is enormous variation in what people will consider a crisis and little of it is suicide. In the main, it was relational—difficulty with a newborn child, or panic about an abusive partner. Sometimes it was completely mundane—how to assemble a crib for example. And occasionally quite weird—how to find the tapes that recorded their ascent into the clouds. But it actually doesn’t matter what I thought of these peoples’ crises. What mattered was what was a crisis for them. If it has exceeded your optimal stress point, for whatever reason, you’re in distress. Too much distress and you’re in crisis. This has very little to do with what other people think about your stress.

But, despite this sometimes rather alarming variation, we do have some control over our curve. We often make some challenges threats. But equally, we can make some threats into challenges.

These changes come about according to our sense of control.

For example, let’s accept, for the moment, that Trump truly personally represents some threat to democracy.4 We could allow that to be a cognitive priority, but there is frankly little one can do about it.5 Similarly, we could allow the war in Ukraine to occupy our minds—we could even throw in some other wars for free. But again what, precisely, are you going to do about it? These are both more-or-less a case of Postman’s “news from nowhere about nothing”—features of the world advertised to us about which we can do very little—with all the tension that entails. To quote myself on another case of ‘nothing from nowhere’:

Typically, conspiracy theorists are in a minority. They wield little power. This question of the balance of power is a fundamental contributor to emotions like anger, and hate. Those who concern themselves with things like ancient aliens or flat earths are often seen delivering angry diatribes on and offline. That underlying anger is almost certainly compounded by the fact that they are treated as deluded and they have little power to make change.

This is an example of shifting our curve—allowing the issue to create more stress than we can manage and we can’t manage it because we literally cannot manage it. That is the very distinction between threat and challenge: a perception of control.

Knowing this, we can push the curve the other way.

Carol Dweck’s growth mindset might be the most well-known example of this. Again I quote myself:

this article from ‘Psychology Today’ … encourages the growth mindset—thinking of a “setback as a lesson to grow from instead of a failure to endure…what you can learn from difficult outcomes or failures and use them”. Of course, this seems more like an activity than a ‘mindset’

I am critical of its usage there because:

‘growth mindset’, as originally conceived of by Carol Dweck, is actually a complex system of beliefs and automatic thoughts that are typically developed in childhood and may have substantial impacts on lifelong achievement. A bit more involved than simply ‘learning from our mistakes’.

But these two facts are both true and crucial. Moving our curve so more threats become challenges is exactly an activity, and a lifelong one at that. It’s not so much the “hard times and oppression” that help us “develop psychic muscles”. It’s what we do with those times that makes the difference.

A rather intense example. It is a remarkable finding that torture survivors are often more resilient than other refugees, “even though they have worse physical health, higher trauma load, and mental health symptom severity, compared to other refugees”. That is, they seem to recover following their more severe traumas equally or better than the somewhat less severe traumas of other refugees. Why? Well, the common explanation is that they find solace in their collective identity. They perceive that they have “sacrificed themselves for their group identity and or for its cause”. They have transformed something fundamentally uncontrollable into something they did, not something that was done to them.

The notion of ‘Post Traumatic Growth’ discussed in that article is a fairly well-discussed one in clinical circles. All find that this kind of growth follows a similar kind of re-appraisal. This review for example finds that post-traumatic growth is a product of ‘reappraisal of life and priorities’, ‘development of self’, and ‘existential re-evaluation’ that the trauma led to.

This should be completely unsurprising because the entire discipline of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, the dominant feature of western mental health for the last 30-40 years, is based around the same idea. Re-appraising our automatic thoughts and behaviours in the face of more positive evidence than the twisted reality our minds are apt to present to us. Indeed, researchers love the idea so much they keep finding and re-finding it under new names. For example, we’re now well into the mindfulness revolution, which is CBT dressed up in pseudo-Buddhism. Here psychological flexibility, the ability to “recognize and adapt to various situational demands; shift mindsets or behavioral repertoires when these strategies compromise personal or social functioning; maintain balance among important life domains”, is explored for its fundamental contribution to mental health. Here, the resilience inventory “draws together 15 years of research and proven techniques” around evaluating “the impact of thinking on emotions and behaviour”. And here, distress tolerance is a protective factor against psychopathology. As a brain scientist, I could probably say something like, it’s a matter of establishing new patterns of neural functioning that are more adaptive, which requires the retraining of neural pathways through thought and behaviour. Oh wait, I don’t need to, here’s someone doing exactly that.6

If we abstract beyond the jargon, all the literature is saying is that transforming threats into challenges is a process of reflecting on how controllable the events are—what is it that we can do, rather than what is being done to us. We are shaping the interactions, not letting the interactions shape us.

This is all probably surprising no one. But it’s striking to me how little people do this. Again, this is partly because so much of the information we consume comes ‘from nowhere’ and is ‘about nothing’: information we can do nothing about. But I suspect that it’s also because we intuitively don’t understand that our psyche has ‘muscles’ in a very similar sense to the rest of our bodies. If we spend our time focusing on the lack of control, we will become very good at that. If we spend our time focusing on what we can do, we will become very good at that.

I’m actually getting distracted here, because I find this very frustrating. This was not supposed to be the point of this article. But since we’re here I will give two very concrete and common examples:

- Low self-worth is very common, and in this case we look to others to determine our worth. This is absolutely not going to help. We need to concentrate on examples of things that made us proud of ourselves. A really good place to start is by reflecting on the fact that we’ve decided not to outsource our worthiness in the first place! Well done. Now do that same kind of reflection as much as you can manage. Every time you catch yourself wondering if you’ve met someone else’s standard, try and work out what your standard is and if you’re approaching that.

- Low self-esteem is also very common, and in this case we reflect often on how inadequate we are at whatever thing. This is probably not helpful, unless the stakes are high. But most people are not doing high-stakes things. When you catch yourself reflecting on how inadequate you are, spend some time reflecting on how you’ve improved on that thing. Not disingenuously, but with some serious identification of the details of improvement. Now do that as much as you can manage.

It sounds patronisingly trivial, but it works. It works amazingly. But it absolutely doesn’t work if you just do it once. You have to do it all the time. They are psychic muscles, not psychic switches. And indeed, there are caveats. So let’s hurry up and get there because that was one of the actual things I wanted to write about.

The underbelly of the psychic muscle

Alright, so I guess now we’ve over-covered a fairly mainstream idea that no one actually does despite all the evidence that it’s the only reliably useful mechanism for change we’ve discovered, let’s move quickly through what I wanted to talk about.

Part of it is above. This notion of psychic muscles is hugely powerful. But this doesn’t have to be framed purely in the context of a threat mindset vs a challenge mindset. We are encouraged to ‘see the opportunities in difficulties’, or manage the ‘alarm bell’ in the brain or whatever, but all we’re doing here is one kind of exercise. Not great for actual muscles, not great for psychic muscles.

The most outstanding exercise I have ever seen or deployed in a counselling context was the absurdly simplistic-sounding “five things I’m grateful for” exercise.7 Here you are told to write down, ho-ho, five things you’re grateful for every day. You have to bring these to the next session. Within two to four weeks people report much higher moods. Why? Because you know you have to write these things down and present them, you slowly start to orient to these things habitually. The first night you think, “oh-no, there’s nothing, my life is a bleak midwinter”. Eventually you scrawl out nonsense like “I’m grateful for my blanket”, and “I’m grateful I’m not starving”. The next day is probably similar, and maybe the next day after that. But soon enough you find yourself going “oh, this here is a really nice moment! I’ll have to remember this so I’m not writing nonsense for my five things I’m grateful for tonight”. Within weeks, you’re just generally paying more attention to this pleasant moments because you’ve trained yourself to and so of course you’re feeling better. You’re noticing more goodness. Now, this exercise, like any exercise, will eventually lead to a plateau. Your psychic muscles get used to the weight, and you need to train in some other way to improve further. But the lesson is clear. We can sensitise ourselves to general goodness, not just to opportunity.

The second point goes back to the quote at the start, which was actually what I was hoping to concentrate on in this article. The literature on Post Traumatic Growth, and much of the other literature on re-appraisal, points out that experiencing more difficulty—if we feel a sense of control or mastery over those events—actually improves our tolerance for distress. Simply having more examples of successfully negotiated challenge shifts our stress curves in the better direction. I suppose, given all the elucidation on the related concepts here I don’t actually need to go into this much, but indeed:

People need hard times and oppression to develop psychic muscles.

Relatedly, and hinted at when we spoke about our torture survivors, there is a sort of cheat code to successful negotiation of challenge. There are a number of highly-related ‘personality traits’ that, despite my skepticism around personality traits, predict very well long-term performance under stress and wellbeing in the face of difficulty. These are called things like conscientiousness and grit and need for achievement, but seem to mostly map onto something like perseverance of effort. Many things unearth such tendencies in us, but they all reliably appear in the presence of an ‘other-related’ motivation. That is: a sense that the effort we are putting in clearly has a beneficial effect on the lives of others. A passion, a purpose, a moral hook, education about the lives and perspectives of others, attending to social reciprocity;8 when we can connect what we’re doing to the lives of others, we’re far more likely to perceive a challenge in the stress than a threat.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, not everything is within our control. It is, for example, very unclear to me how controllable the threats that emerge from something like complex PTSD are. Run of the mill PTSD is already pretty difficult to treat with CBT-style interventions, and complex PTSD comes with so many co-morbidities that a simple “how grateful am I” activity isn’t going to do a lot. The same is true for many psychopathologies. But also, many things that are not psychopathologies are difficult or impossible to control. “News from nowhere” is one. You can’t do anything about Trump. If they couldn’t get him with a narrative about literal revolution, what have you got left? The people on Trump’s side also can’t do anything about the people they’re freaking out about. They did a literal (if fairly benign) revolution and nothing happened. It’s the same with Ukraine. You can donate your money and your time, or perhaps you could even go over there to fight. But absent this, and even including this, this conflict will play out like all conflicts: in a way that is affected very little by your participation.

In these uncontrollable cases, all we can really do is avoid exposure to the threat.9 Not all reflection is useful reflection.10 It’s only useful if we can (and do) pull out the aspects we can control. This is rather important advice because, contrary to the enthusiastic adoption of ‘growth mindset’ as a term, the malleability of our stress curves is probably over-emphasised. We can push our stress curves more toward challenge, but only so much at once and maybe only so much at all.

We are each maps of the scars that brought us to where we are. Perhaps there is little we can do about the scars, but at least there is something we can do about the memory of what put them there. That is the secret of the science of discontent.

The least charitable account of the article would wonder if they’d ever read Edmondson’s work, which right up in the abstract implies risk-taking is important for performance and psychological safety is a mechanism to encourage it. Certainly not quite the same thing as the ‘handicap’ to ‘strategic thinking’ the article depicts. ↩

Lately, the predominant concern is about the nuclear risk posed as the Russian invasion has stalled. I’m also pretty worried about this. But not that long ago, the nuclear risk was not a particular concern. In my examples, the topic of nuclear risk was never raised. ↩

And he might be, honestly. It’s not clear that the kind of problems we’re seeing wouldn’t have occurred without Trump, but it is clear that he taps very effectively into something quite problematic indeed. ↩

Except apparently write a bunch of ad hominem articles that do a dubious job of convincing the people that don’t agree otherwise. ↩

I literally copied this sentence and prepended ‘wellbeing’ and this was the second academic result. The first was this: a classic brain scientist attempt to, I guess, find where wellbeing lives in the brain? ↩

A variation of positive psychology’s famous three good things intervention. ↩

See also a narrative of grit and accidental talent. ↩

See also repressed memories. ↩

I’m getting tired of writing this article now, but I am tempted to go into a tangent on the difference between practice and deliberate practice. Just as practice without the right kind of effort is not particularly useful, so too is reflection without the right kind of effort. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.