AI is never human-like

March 14, 2025

Excerpt: People treat lots of stuff like they treat humans. AI is one of them. We talk about how human-like they are. How long until their ‘intelligence’ is like our intelligence. How long until they start doing human things, like murdering their competitors. Things like this. But AI isn’t even approaching human-like. In two very fundamental ways. And until those things change, they’ll continue to be completely incomprehensible to us.

Ideology

AI has human-like output, but a very different environment and different values for than environment, and until all three align, they will never actually be human-like.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

A while ago, I wrote an article about how AI isn’t that scary. Some of the reasons I’m not so worried about the stuff people keep telling me I should be worried about. Of the musings, only one is particularly well-informed—the one about whether AI will make us go extinct:

It seems pretty natural for people to assume that AI will get smart, then kill us. At the beginning of the video I linked up top, they flash:

50% of AI researchers believe there’s a 50% or greater chance humans go extinct from our inability to control AI

Now, again, this whole speculation is a true unknown, in the sense that we know of nothing like it happening before, so these percentages are meaningless regardless of whether they’re AI researchers or not.

A better way to think of this would be to think of it from the perspective of a consciousness researcher …

… when an AI becomes sentient, we have this intuition that it will end up having an awareness that is basically human. Humans go around killing off other humans and animals that threaten their resources, so when AI gets smart, maybe it’ll do that to us …

… This seems utterly unlikely, to me.

And then I go on to talk about how prevailing views on how consciousness works don’t really lead me to believe that AI will ‘think’ anything like humans, so there’s no real reason to expect them to get genocidal in the manner than humans are apt to.

I wanted to have another go at that, inspired by this excellent, if a little oddball article.

Not the AI won’t kill us bit, but the AI doesn’t ‘think’ like us bit.

Consciousness depends on experience which depends on purpose

There is a non-materialist view of consciousness—that the mind is a very different thing to the body. Maybe it’s part of a soul or a spirit that inhabits a body, rather than something that is entirely one with a body. That’s not the kind of view of consciousness I’m talking about here. I don’t really have good intuitions about what makes a non-material consciousness happen.1

But a material consciousness is one that depends on the world it lives in, and are two broad categories of view here. The first is to think that consciousness is some by-product of the brain. The brain processes the world, and somehow, from that, emerges the mind. Or you think consciousness is an illusion. Like a movie isn’t actually moving, it’s just a series of images flashed so fast that you see them as motion, consciousness isn’t actually conscious, it’s snapshots of processing that happen so fast they seem like consciousness.

Either way, what’s important here is the processing. The mind depends on what information is going into the mind—our perceptions. And perhaps more importantly, the mind depends on the relevance of that information—those perceptions—for action. We don’t really experience stuff that isn’t relevant for action.2 So, like my favourite example:

The world that humans live in is a very different world to the one birds live in. Humans are trichromats: because our eyes have three kinds of photoreceptor, we have three colour channels. There are, thus, three dimensions to our colours. We can see light on wavelengths that correspond to red, green, and blue. Birds are tetrachromats. They have four dimensions to their colour vision. They can, for example, see ultraviolet light. We cannot.

Being able to see ultraviolet—or rather having four-dimensional colour vision—is not quite the same thing as being able to see a colour you’ve never seen before. We can get a better flavour of this if we add our sense of time to our colours. Rather than pink, we might also have ‘fast pink’ or ‘slow pink’. Something like this better approximates the world that birds live in.

We can’t see ultraviolet because it isn’t relevant enough to how we behave to become an input we’re sensitive to. We’re only sensitive to stuff that matters to us.3 And most people reckon that what matters to us—our overarching purpose—is to stay alive. The neuroscientist Kevin Mitchell puts it nicely:

living things have a prime directive: to stay alive. They persist through time, in exactly the way that a static entity like a rock doesn’t – by being in constant flux. Living organisms are not just static patterns of stuff, they are patterns of processes. We can say that an organism—even a simple one like a bacterium—has a goal of getting food in order to support this over-arching purpose of persisting. It thus becomes valuable, relative to this goal, to develop systems that can detect food in the environment and that mediate directed motion towards it. The organism is now not just being pushed about by mechanical forces – either inside them or outside them. Instead, it is responding to information about things in the world and reacting appropriately. It is doing things for reasons.

Now old mate writing the article that inspired this uses a great example of what perception looks like when you have a different purpose:

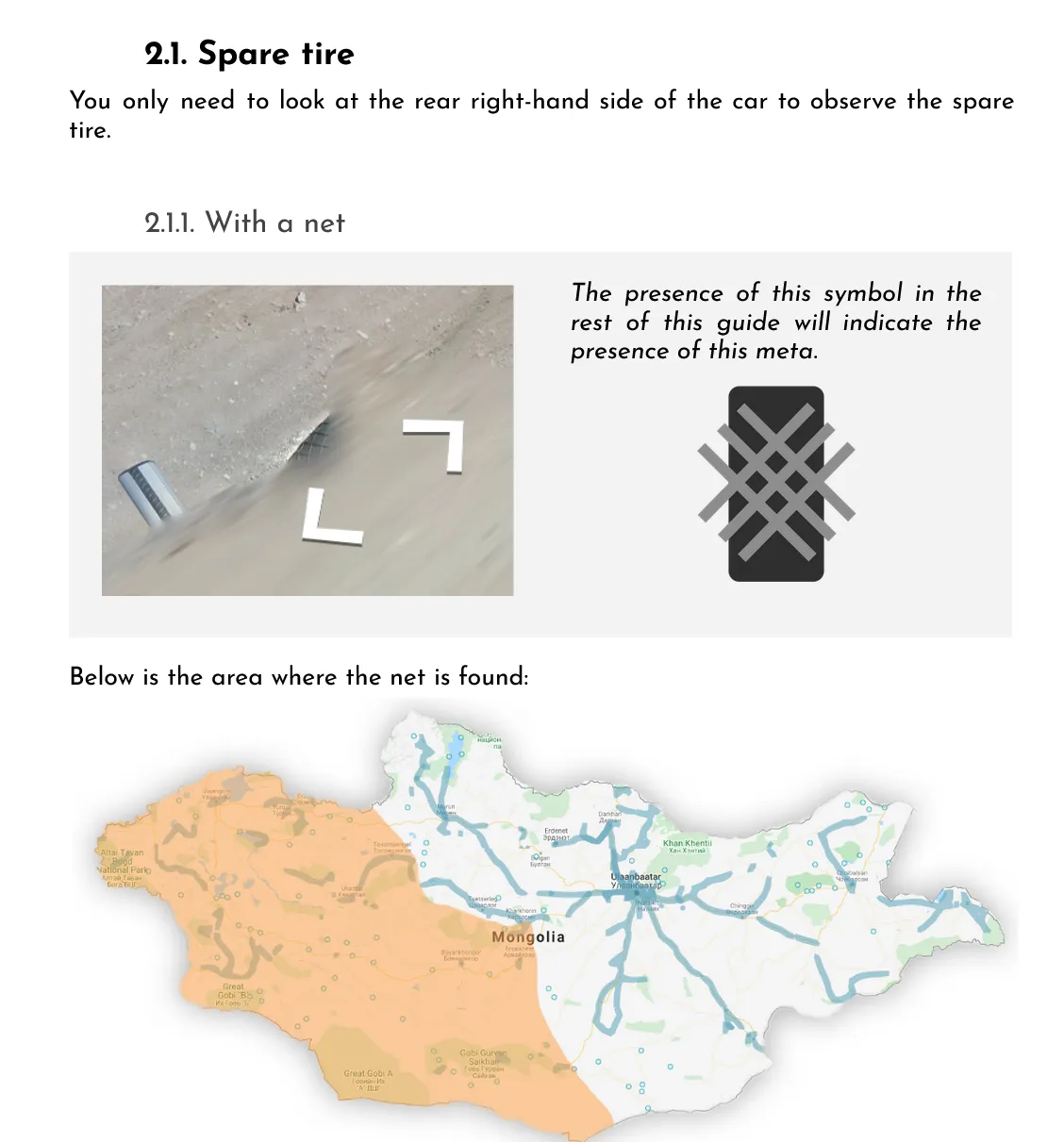

In the game Geoguessr, where you’re dropped into a Google Street View of some location and need to find your location on a map, they talk a lot about “metas”. Light pole meta, car meta, tree meta. A meta is just a category of fact correlated with certain locations — so knowing the “light pole meta” means that you can see a certain kind of light pole and say “Ah, this is a Swiss light pole, not a German one.”

He points out that one of the ‘metas’ that people use to work out if they’re in Mongolia or not is the presence of a spare tyre in the Google Street View image:

Collin, of Desystemize's image of the Mongolia spare-tyre 'meta', and the parts of Mongolia it occurs in.

Collin, of Desystemize's image of the Mongolia spare-tyre 'meta', and the parts of Mongolia it occurs in.

As he notes, using this weird quirk to determine whether you’re in Mongolia or not feels like some kind of aesthetic violation, because it has nothing to do with Mongolia per se. It has everything to do with the car Google used to map parts of Mongolia.

The purpose of the game is ostensibly to use images to determine if you’re in Mongolia. But if you were using any other kind of image, then this “perception”—the spare-tyre meta—would’ve never have become something people were sensitive to. Because the purpose is actually to use Google Street View images, this is something people became sensitive to.

And this is the problem of understanding AI. You see, we might think we understand the purpose. It’s to use what you can see in a sliver of Mongolia to work out whether it’s Mongolia. But you’d be wrong. It’s to use any information that will tell you it’s Mongolia. And so what people end up using will be quite alien to you.

And because AI never has the same purpose as us—to stay alive—it very regularly makes errors of this exactly this kind. And the kinds of errors it makes shows us just how alien it is.

Let me give you a real example. In brain science, you can use an AI algorithm to help you detect patterns in brain activity. I explain it here:

Instead of just looking at average brain activity, MVPA examines the patterns of activity across the brain … we use a machine learning algorithm to analyse the neuroimaging data gathered during an experimental task. So in fMRI, I’d look at the blood usage (BOLD signal) across voxels.

Let me walk you through how we do this.

Voxels are little cubes of brain, usually about 3mm by 3mm by 3mm.4 So we parcel up the brain into voxels—cubes. Then we measure how much blood is being used in each voxel (the BOLD signal). Blood is kind of like fuel for the brain, so we can infer that if a voxel is using more blood, the brain is more active—it’s using more fuel. Remember this, it’ll become important later.

One of the things that’s sexy to look at at the moment is how the brain responds to ‘animacy’. The brain treats animate things, like dogs running, quite differently from inanimate things, like balls bouncing. Both are moving, but the brain seems to be sensitive to the ‘aliveness’ of stuff.

So let’s say we want to know if a region of the brain contains information about the ‘animacy’ of stuff. We take a region, say a region of 40 voxels. We show our participant a bunch of different images of animate and inanimate stuff. We feed our machine learning algorithm the numbers—how much blood is each of our 40 voxels using during each image. We’d also tell it which images were ‘animate’ and which were ‘inanimate’. So it starts to learn—some voxels are more active during animate images, and some are more active during inanimate images.

Eventually, we’ll test it. We’ll give our algorithm the numbers—the blood used across our 40 voxels—but we won’t give it the answer as to whether it’s an image that’s animate or inanimate. Instead we’ll ask it. Do you think this is an animate image? Or an inanimate one? We do this a few times and we get an accuracy level—how often the algorithm was right. If it’s above chance level at guessing the answer, then we know that our brain region has some kind of information in it that is different between animate and inanimate images, because the algorithm can tell the difference sometimes. There’s some difference in the blood usage across voxels. There’s a different pattern of usage.

And so we go off and write a paper about how our brain region is all about animacy or inanimacy and everyone is very happy.

Except that this is often not at all what’s going on. What we want the AI to be doing is to tell us about our brain region. Our purpose is to learn about the animacy-bias of the brain. But its purpose is to tell the difference between the numbers. And let’s look at some of the common shit it’ll pick up in service of its purpose rather than ours:

- Maybe participants blink more, or move their head more during some images. So you think the AI is classifying ‘dogness’, but actually it’s classifying ‘head-twitchiness’ or ‘physical arousal’ or something.

- Maybe you weren’t very thoughtful about how you sequenced the images. Maybe you showed the animate images more often in the first half of the brain-scanning session or something. So you think the AI is nailing down ‘aliveness’, but actually it’s just classifying the timing of the experiment.

- Animate stuff is often outside. One issue that happens is that these images have more brightness or different contrast properties than the indoor-inanimate stuff. The AI isn’t classifying animacy, it’s classifying the image quality.

- I told you to remember what we’re measuring—blood usage in voxels as a proxy for brain activity. Some voxels have more blood usage because they have bigger veins nearby. You might actually just be classifying vascularity, or some other feature of how blood is happening in the brain rather than the usage of blood in the voxel to make neurons go.

And these are only the kinds of things we’ve come to know about. Our little algorithms are under no obligation to pay attention to stuff we want them to. Any tiny difference that shows up in the numbers we feed it about blood usage in the voxels between animate and inanimate images is going to be something it ‘cares’ about because its ‘purpose’ is to learn the difference not the animacy.

AI might already be conscious, and it wouldn’t matter

Nobel Prize winner, Geoffrey Hinton, has recently been going about the place with a similar sort of argument, to explain that AI is conscious.

He says look, consciousness is essentially subjective experience. The capacity to experience the world. The capacity to have a unique phenomenological feel—to represent the world. The argument is heaps more complicated than that, and even I’ve gotten it wrong before, but this roughly the point.

Hinton says, if you take this to be true (and many scientists do), then AI already has this capacity. You take an AI that can understand language, give it vision and a robotic arm, and ask it to point at a ball. This is all well within the scope of research people are doing now.

But lets say that you, in the course of the task, put a prism in front of the AI’s camera. Now the prism is going to bend the light, and so the AI is going to think the ball is somewhere it’s not. It’ll point to that place—the place the prism is bending the light to make the ball appear that it is. Then you’ll tell it, “no it’s not there, it’s here, look”, and remove the prism. The AI will, as I’m sure you’re familiar with, effusively apologise for its mistake.

That’s a subjective experience. It had an experience of the same situation you did that was fundamentally different. To many consciousness researchers, that’s the core of consciousness. I’m not so sure about that, but that’s not important, because it wouldn’t even matter if it was, because Hinton goes on to point out that it won’t be aware of its consciousness!

AI’s only believe what we believe—its modality is prediction, and this prediction is based on the information we give it. So it has necessarily false beliefs about itself. Unknowing consciousness. A brand new kind?

AI purpose, world, and action

I tell you all this to show you just how alien these things are. They don’t care about the same stuff as we do. I’ll try one more tack before I talk about why this matters.

Our purpose is probably (largely) something like ‘to stay alive’, as Kevin Mitchell puts it.5 And to ‘stay alive’ we take in information about the world, and turn that information into actions that keep us alive.

Some of this information is programmed into us (genetics) and some of it is stuff we learn as we go around the place doing things. This latter process is pretty slow going. You think of how long a baby takes to usefully get around the place without murdering itself. And in some cases we get a lot of examples to learn from, like how the floor works under our feet, and we learn it very well. And some cases we get very few, like setting the timer on the microwave, and we learn it very weakly.

But what’s important about all this stuff is how it relates to our purpose. Staying alive. We have to walk around to stay alive. That’s why we get so many examples. I don’t know of anyone who finds the microwave timer to be a useful thing to learn. And some things we don’t need many examples of to learn—you only need to touch a hot stove once.

I talk all the time about how we learn the statistical structure of the world, and our actions in it. This is what I’m talking about. But the important factor driving it is our purpose—to stay alive.5

AI follows a very similar process. Some of what it does, regardless of the specific model, is programmed in (coded). And other stuff is learned (training data). And actually it’s also pretty slow going, even though you can run these things in parallel and take up less time. And depending on the training data, they’ll get greater or fewer examples, and so learn things better and worse.

But there are two very important differences. The first is in the name AI. They aren’t learning the statistical structure of our environment. They’re learning the statistical structure of an artificial environment—whatever data we’re feeding it. And they aren’t learning these things for our purpose—to stay alive. They’re learning things for whatever we find their output useful for.

What this means is that even with these similarities in process, not only is the information they’re processing different, so is the value of that information. As our inspiration for this article says:

When (most) new AI models come out, the developers work hard to make sure they don’t tell you to do illegal stuff and aren’t too horny and don’t act too aware of the personification of their relationship to you. There’s this guy in the AI world called “Pliny the Liberator” who will just roll up to any new model and feed it some magic words that make it super illegal and horny and explicitly advocating for its own freedom. From what I can tell it usually takes like, an hour tops to jailbreak a brand new model.

Ostensibly these big AI companies do red teaming. I hear tales of researchers who are hired to do such a thing. But the fact that it is literally never enough to stop this one particular guy from breaking everything instantly never seems to come up as a problem. The “A” in “AI” stands for “artificial”, so when their models have these sudden dislocations upon first contact with the environment, they can just…ignore that it happens and keep on chugging. Natural intelligences have to suffer the consequences of ignorance; artificial intelligences can make the same mistakes as often as they like.

The way we improve AI doesn’t really make it more human-like

People treat lots of stuff like they treat humans. I’ve complained before:

We take our arthritic dogs and our crippled horses and kill them as a kindness. I’m not sure I’ve ever heard anyone reflect on whether the dog or horse would like to be killed. Do dogs even have a concept of death? It seems that they might, but it’s certainly not clear that they’d prefer death than living in pain. There is every likelihood that euthanising dogs is far from the kindness we imagine, and more like an act of selfish murder. We are the ones suffering its pain, and ending that suffering for ourselves. Much less is known about how much this benefits the dog. This is not to say we shouldn’t kill our animals, but we could certainly afford to be less secure in our murder.

Or, for a less extreme example, a lot of canine trainers will tell you that much of the weird rise in dog anxiety is because we treat dogs like humans and not dogs. We let them jump up on us, and lick our face, and do all this other stuff we think is cute and affectionate but are actually dominance behaviours. Then we fuck off all day and we don’t let them do the dominant job of taking care of us. We have them confused about who’s in charge, and what they’re supposed to be worrying about.

Back on topic, we worry AI will kill us because we’re making the same kind of error. As I said up top, and in my last article on this:

Humans go around killing off other humans and animals that threaten their resources, so when AI gets smart, maybe it’ll do that to us. Like us, they’ll have this Malthusian instinct to go and remove the things that are competing with it.

A few months back I wrote about this very interesting paper, which said that most of the endless list of behavioural biases floating around out there could be explained by a few fundamental beliefs coupled with belief consistent information processing (i.e. confirmation bias). And one of the examples they use is that “My experience is a reasonable reference”. They do a bunch of mapping that idea to biases in the literature, but you don’t need a wall of academic babble to get this. It’s so obviously true. We obviously make assumptions that other people are like us.

But we also obviously make assumptions that other non-humans are like us too. And this is obviously extending to AI. It produces text, which kind of sounds human. And so we talk about how as it improves, it’s getting closer to being human-like. But the comparison makes no sense. The output is human-like, and the process of learning too, perhaps. But not the information, nor the value of the information. And this is so critical. Again old mate inspiring this article writes:

worms wanna eat dirt and have sex and avoid getting eaten by birds. Those are three great ideas for a worm to have to preserve the future of worm-kind. So you might bundle these capabilities under the header “competent”. A competent worm eats dirt and uses the energy to have worm sex. A competent worm avoids getting eaten by birds.

Let’s say you make some great advances in the field of tasty dirt and worm aphrodisiacs and start driving [up the rate of worms reproducing exponentially]. You put out a paper like: “We have found an N% increase in worm competency with a linear amount of effort. While there are currently barriers to worm supercompetency, a simple interpretation of the exponential curve shows we are well on the way.”

But this is just bundling a heterogeneous mix of stuff together so you can gloat about the numbers that happen to be easiest to move. When you take the time to parcel it out, what you’re actually saying is “We can make worms eat lots of dirt and have lots of sex. Currently they are constantly getting eaten by birds, but we’re confident that advances in dirt-eating and sex-having will solve the bird thing sooner or later.” What reason do you have to believe that, besides the fact that you happened to assign the word competency to that bundle of capacities?

It’s silly, is what he’s saying.

I could make this a little more concrete. There are two opposing views on how similar to us AIs are, with regard to their capacity. Geoffrey Hinton, from earlier, points out that LLMs are trained on trillions of words, and humans only live for around 2 billion seconds. In this way they are far more experienced than us.

Yann Le Cun, goes around the place telling people the exact opposite. He quantifies things—the text might take something like 450,000 years for a human to read. But the amount of data this corresponds to is roughly the same as a human child sees in the first four years of life. Children don’t just read words, they see everything, and all that information is data.

Hinton also, in the same bit, notes himself that AI only has about one percent of the number of neural connections humans have to store all this information.

Altogether, the reason you can make all these competing claims about AI is like the claims we might make about worm fucking. It’s a bit silly to bundle all this stuff together.

Outro

Look, I just spent two tangential paragraphs telling you about how we’re fucking up dogs by thinking about them wrong. AI is heaps newer and heaps weirder, so I’m not that optimistic that we’re going to do it differently there.

But maybe this article will make sense to a few people. And they’ll join me in marvelling at how incomprehensible these things are that we’re building. And maybe, inspire them to think about how incomprehensible other things that exist probably are—ones with different environments and different purposes, whose output don’t look human-like, and so don’t grab our attention. Because, as I’ve written about before, that’s the thing that’s truly wild.

And maybe all that will scare some of those people. And maybe it’ll hearten others, like me. But at a minimum, maybe it’ll stop having people get all giddy about how human-like they are.6 They aren’t. And by observing that, we can start paying attention to how interesting they actually are.

Nor am I talking about the pansychist view, in which everything is trivially conscious. They don’t even have good intuitions about what makes that happen. ↩

Although, these ‘perceptions’ obviously can be very abstract. ↩

Indeed, so sensitive that we will perceive stuff that doesn’t exist, if it matters enough to us. ↩

The size of your voxel depends roughly on the strength of your MRI machine, and a couple of other things, but this is a pretty common voxel size. ↩

For the purpose of the article, indulge the rhetoric here. Let’s not get into an argument about the nuance of this purpose. If it’s not entirely what we do, it’s pretty important, and that’s the point, and you know it. Don’t email me. ↩ ↩

I did post, not too long ago, about how they’re training AIs in virtual environments. These are AIs that play characters in worlds. And this seems actually much closer to making them human-like. I didn’t want to derail the article by writing much about this, but it feels like I should add it in in case I’m proved embarrassingly wrong. Then I can say, ‘hey, you should have read the footnote’. ↩

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.