Nervous Energy

October 25, 2024

Excerpt: A very basic principle of living creatures is that they respond adaptively to the environment. It isn’t the only principle. But it’s really rather important. And more-or-less, this principle is what the nervous system does. But many people talk about the nervous system in mystical tones—the key to altering your maladaptive responses. Sadly, these people have no idea what they’re talking about.

Ideology

The nervous system teaches us the most important lesson about human behaviour: the main thing our body does is transform the world into adaptive responses, and the nervous system is at the very core of it. But beyond that, it’s mostly just a mess.

Table of Contents

filed under:

Article Status: Complete (for now).

A very basic principle of living creatures is that they respond adaptively to the environment. It isn’t the only principle. But it’s really rather important. And more-or-less, this principle is what the nervous system does.

A principle of living creatures

All animals have some kind of system for this: a system that takes the information from the environment and converts it into behaviour that will make the environment more good, or less bad. Let me quickly show you what I mean, before we get to the nervous system. As I’ve pointed out before:

the single-celled bacteria, E. Coli … lives in a very simple world, comprised only of different chemical concentration gradients … The thing that determines the bacteria’s behaviour is the concentration of chemicals in the solution it inhabits. E. Coli will move towards nutrients like glucose, or away from toxins like phenol … E. Coli moves toward the good, and away from the bad.

But because the world the bacterium lives in is so simple, it only needs two behaviours to get this sorted out. It has a ‘wiggle forward’ behaviour, and a ‘tumble randomly in a new direction’ behaviour. If the concentration of glucose is increasing or maintaining, it’ll ‘wiggle forward’. If the concentration of phenol is increasing, it’ll ‘tumble’ until it’s wiggling forward has the concentration going down. All this is achieved by molecular signalling pathways. No nervous system at all.

In the same article I also use flowers as an example:

Many flowers, like sunflowers, move in order to maximise their position in relation to the sun; a property known as phototropism … In some cases this property appears to be purely mechanical, but phototropism can be quite complex, involving multiple signalling pathways, photoreceptors, and hormones to coordinate differential growth gradients. Even in the relatively static world they live in, flowers seek out the good and avoid the bad

Flowers take in information from the world, and convert it into adaptive behaviour. And again, because their world is so simple, their behaviour is correspondingly simple. A contraction of cell walls, to bend the flower’s stem, or as in the bacteria, molecular signalling pathways.

Humans live in a very complicated world. And so we need a complicated conversion kit. Hence, the nervous system. We take in information about the world through our senses. This gets passed to our sensory neurons—nerves located near the sense organs, in your skin or within your muscles or by your eye. These neurons pass that signal to interneurons, usually in your spine. Those pass the signal along to more interneurons, and more, until it gets to your brain stem and often a structure in the middle of your brain called the thalamus—a sort of ‘relay station’. As it gets bounced from there, among the interneurons in the brain, the information will be transformed from the perceptual information it came in as to the motor (movement) information it needs to go out as in order to manage the environment, eventually passed on to motor neurons which lead back to your muscles and such and making your body do the behaviour it needs to do. Along the way, it will grab things it needs from various collections of neurons in the brain, like your stored memories and and whatnot, so it can make more fine-grained actions based on more information.

See, with a nervous system like this, we can convert much more environment into many more behaviours. And the information can travel more or less of this journey, depending on the complexity of information. For example, some reflexes never need to go all the way to the brain. When the doctor taps your knee with that little hammer, your spinal cord has all the information it needs to send an impulse to kick back to your leg.

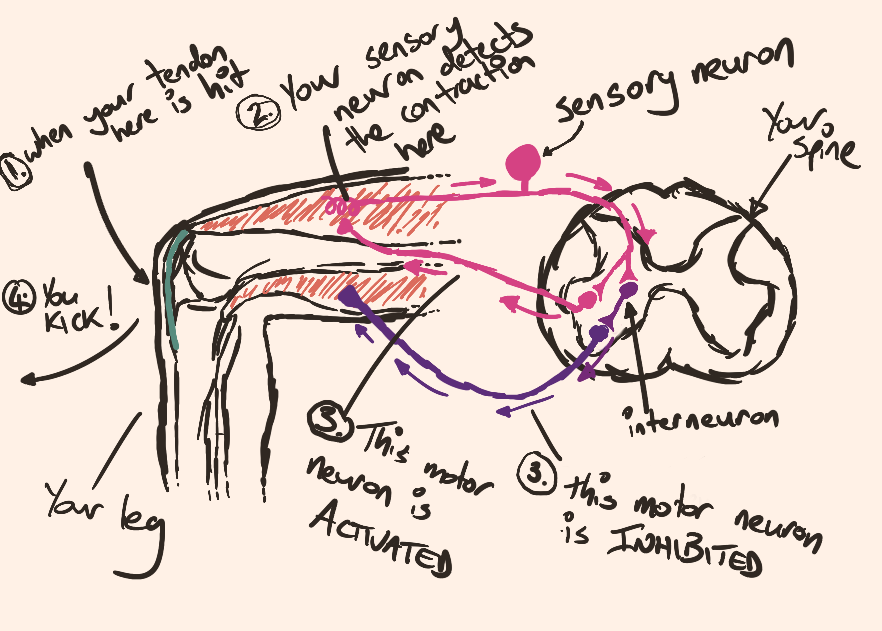

This is my attempt at drawing the knee jerk reflex. Basically, when the

doctor taps your tendon connected to your quad muscle, the muscle

stretches. Sensory neurons in the muscle detect this and rocket a signal

to the spine. There, the information splits---the sensory neurons pass it

back to motor neurons in your quad, activating it (kicking out your lower

leg), and some interneurons catch the signal going by and pass another one

on to your hamstring to stop the hamstring resisting the kick. This all

happens from the leg to the spine and back---no brain involved. Though of

course, other signals are passed to the brain---you notice it, wonder why

the doctor is hitting your knee, wonder if you should ask, chicken out,

tense up in case she's planning to hit you again somewhere less opportune,

wonder if your reflex was reflexive enough or maybe it was so weak because

you have a rare cancer of the knee, etc. As I talk about later, there's

often no real reason to distinguish the brain from the rest of the nerves.

It's all a big interconnected mess.

This is my attempt at drawing the knee jerk reflex. Basically, when the

doctor taps your tendon connected to your quad muscle, the muscle

stretches. Sensory neurons in the muscle detect this and rocket a signal

to the spine. There, the information splits---the sensory neurons pass it

back to motor neurons in your quad, activating it (kicking out your lower

leg), and some interneurons catch the signal going by and pass another one

on to your hamstring to stop the hamstring resisting the kick. This all

happens from the leg to the spine and back---no brain involved. Though of

course, other signals are passed to the brain---you notice it, wonder why

the doctor is hitting your knee, wonder if you should ask, chicken out,

tense up in case she's planning to hit you again somewhere less opportune,

wonder if your reflex was reflexive enough or maybe it was so weak because

you have a rare cancer of the knee, etc. As I talk about later, there's

often no real reason to distinguish the brain from the rest of the nerves.

It's all a big interconnected mess.

And really, that’s it. You could stop here, and your understanding of the nervous system would be pretty complete. But lots of people talk about many more parts of the nervous system, so let’s talk about them too.

The Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems aren’t often usefully distinguished

We often distinguish between the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS isn’t what people usually think about when they think about the nervous system—these are the nerves in the spine and the neurons in the brain. The nerves in the spine act as sort of a ‘highway’ to the brain, and then the brain can do a bunch of additional transforming of that information before it sends it back out again through the spine.

The PNS is normally what people are thinking of—the nerves in the body that feed the CNS—acting as a bridge between the neurons in your spine and your senses. The PNS is the one that takes in the information about the world and information about the body, so that information can be passed along to the brain.

Though this isn’t always true. The peripheral nervous system is much older than the central nervous system, and it can do plenty of processing all by itself, as I illustrated before. The PNS was the brain before brains were a thing. Many animals still get along just fine without a CNS. And in fact, the PNS rents out its own space in the head, in the form of cranial nerves, managing stuff like taste and hearing and facial expressions.

More importantly, there is almost nothing that the central nervous system does that isn’t mediated by the peripheral nervous system, and similarly there’s little the PNS does without some intervention by the CNS. The PNS has first contact with the information, and the CNS and PNS are married to one another all the way along that information’s journey to the brain and back.

So, at the level of the nervous system, we really just want to think about the transformation of information about the world into adaptive behaviour—making the world more good, or less bad—from the time it hits your senses to the time it’s passed back out to your muscles.

Vagus nerves, sympathetic responses, and other woo-woo stuff

I talk quite a bit elsewhere about what the CNS (i.e. the brain) does, so I won’t spend a great deal of time on it here. And really, the brain is better understood at the level of brain structures, regions, and networks,1 rather than thinking about the neurons themselves, when it comes to behaviour.

But the peripheral nervous system has some interesting stuff going on that is worth elaborating on here, especially because it almost always influences what the brain does later. And because people love to misuse the peripheral nervous system to boost their insta followers.

Somatic Nervous System

The somatic nervous system (SNS) refers to all the nerves that manage voluntary control. The nerves that connect to and from your skeletal muscles, so that when you decide to move your hand, your hand moves. The SNS doesn’t have to be voluntary, of course. The knee-jerk reflex I illustrated before is an involuntary use of the SNS. But you can also kick your leg out voluntarily if you want. I don’t really think there’s much more to say about the SNS.

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is where the juicy stuff is. Really, the autonomic nervous system is the brain before the brain in many ways. It manages all the systems that function unconsciously and involuntarily. Your heartbeat. The slow squeezing of your food through your intestine. The bits and pieces that help you pee. Usually, we separate this into three sort-of subsystems: the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system.

The Enteric Nervous System

Once upon a time, you might have heard the parasympathetic nervous system called the ‘rest and digest’ nervous system. No longer. The ‘digest’ bit has its own system now. It’s called the enteric nervous system and its responsible for… well… digestion. Its job isn’t really the interesting thing about it though. What’s interesting about it is that, unlike the other two autonomic divisions, the sympathetic and parasympathetic, it seems like it can operate entirely independently of the central nervous system. It seems like it can operate independently of all the nervous systems. It’s sometimes called the ‘second brain’ as a result. As far as behaviour goes, I’m not sure this is very useful to know, but it does emphasise that the brain is an evolutionarily recent structure, and the body had a lot of ‘brain’ going on long before the brain ever came about.

The Sympathetic Nervous System

You might have heard this called the ‘fight or flight’ system. That’s silly. The fight/flight/freeze response, and probably the newer ‘fawn’ addition, are all accurately known as ‘hyperarousal’. As the ‘hyper’ part indicates, this should be an unusual thing. Most people only experience it in the face of some immediate threat to survival, although obviously what people interpret as a threat to survival can vary.

What the sympathetic nervous system actually does is more fundamental. It’s like an ‘excitability’ system—getting stuff in your body ready to respond to all sorts of stimuli. This includes times when you’re under serious threats, but like everyone else it has a more boring day job. In this case, it involves managing your blood pressure and temperature and metabolism and whatnot so you can go about doing the things you need to do.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System

You might hear this called the ‘feed and breed’, or as I said before the ‘rest and digest’ system. These are cute, but as I pointed out earlier, half wrong. Sadly, ‘breed and rest’ doesnt have quite the same ring to it. ‘Netflix and chill’ maybe? Mm. I’ll work on that.

I guess the best way of thinking about the parasympathetic nervous system is that it balances out the sympathetic (hence, the ‘para’). Where the sympathetic is typically about preparing you to respond to stuff, the parasympathetic is typically about de-preparing you once the stuff is done, so you can be adequately prepared for the next set of stuff. Everything from slowing your heartrate to inducing sweating.

The notable exception to this is when it comes to sex—the parasympthetic nervous system is the one that gets you ready for that. From lubrication to swelling, to moving the semen and oocytes into place and kicking off the arousal cycle. This, I think you’d agree, is not something you’d call ‘restful’. Eventually, the sympathetic nervous system sort-of takes over, making your heart beat faster and escalating your arousal further, then helping with the orgasm and the contractions associated with it. In fact, the sympathetic nervous system is the one that induces the refractory period after the orgasm too—leading to a restful state so you can recover.

So, the parasympathetic nervous system is basically just there wherever the sympathetic nervous system isn’t. If you’re willing to look past the whole sex-reversal thing there, you could call the sympathetic the ‘up’ system, and the parasympathetic the ‘down’ system perhaps. But I mean, really, you could just not really fuss with either. I’ll be very surprised if you learned anything here that’s going to help you behave differently. You have my permission to safely scroll past influencers who pretend that understanding these systems are going to help you sort your shit out.

A special word on the vagus nerve

Listen. It’s just a big nerve. A really big nerve. It accounts for some huge proportion of the parasympathetic nervous system. This is a classic example of the easy measurement bias: people who are talking about the vagus nerve are actually usually just talking about the parasympathetic nervous system because it’s a big and easy to measure aspect of it. I don’t want to hear any more questions about the vagus nerve.

Outro

The nervous system is a funny thing. In part, it teaches us the most important lesson about human behaviour—that the main thing our body does is transform the environment into behavior. We sense the world, process it in our nervous system until it can determine the best actions to make the world more good and less bad, then sends that information to the muscles which will execute it. This happens consciously and unconsciously, at low and evolutionarily more basic levels and at higher levels of more evolutionary complexity. This functionality is at the core of all animals, all the way down to plants, and in understanding this, we can really start to think about what kinds of environmental inputs trigger what kinds of behaviours, and vice versa.

But then, learning about the nervous system sort-of stops being useful. There is a voluntary and involuntary part. There is a more ‘uppy/get ready’ part, and a more ‘downy/get un-ready so you can get ready again’ part. There is a weird part that is off on its own just doing food processing. I don’t really know what you’d do with that information.

If you figure it out, let me know.2

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.