Why the best part of your brain is hiding under the stairs

November 28, 2016

Excerpt: It’s said that art mimics nature, and in this case, the result is absolutely fascinating. Also, I make a Harry Potter reference. Let’s talk about how your brain is like the cupboard under the stairs.

Ideology

On the spandrel effect and the human brain.

Table of Contents

It’s said that art mimics nature, and in this case, the result is absolutely fascinating. Also, I make a Harry Potter reference. Let’s talk about how your brain is like the cupboard under the stairs.

Over time certain physical and psychological traits perform better in the environment than others. This is the process of genetic evolution. The primary mechanism of development is adaption. So, for example, the peppered moth was once peppered white and black, as the name suggests. But as the pollution from the industrial revolution literally darkened the features of the earth, the moth increasingly became more black than white. Where once the peppered variant of the moth was more adaptive in a world undarkened by smog, the black variant was more capable of concealing itself under the new conditions. This process is commonly known as adaptive selection. The trait that is more adaptive is selected for over that which is less adaptive.

Adaptive selection is problematic

One of the problems with adaptive selection is that it’s hard to explain everything in terms of some adaptive benefit. It’s easy to say that having a darker colour is better when the things you’re hiding against are dark or, that having four fingers and an opposable thumb is far better than just having five fingers.

Other things are harder to explain, like belly buttons, or pubic hair. These things are often thought of as by-products of adaptations. For example, belly buttons are the by-product of the adaptive umbilical cord. Pubic hair is a remnant of our hairy past. These no longer serve an adaptive function (that we know about).

So why are they still here? That’s the rub. One logical answer is that while they serve no adaptive function, they also serve no maladaptive function. The whiter peppered moths aren’t around any more because it stopped them from hiding and they were predated upon. But the black peppered moth doesn’t need to be all black. Some flecks of white, grey, or brown might not make it more easy to distinguish. Thus, these more subtle remnants of the genetic past are neither selected for or against.

By-products can be adaptive all by themselves

This is the fun part. First, a lesson in esoteric architecture. Consider the spandrel. If you were to design an archway for your doorway, you’d fill the corners in with wood to round the edges. Those wooden fillers are spandrels. Architects, artists as they are, began to fill those spandrels with beautiful and intricate designs. All of a sudden, this useless empty space becomes something beautiful and useful.

The cupboard under the stairs is another example of this spandrel effect. Stairs are useful mechanisms to get from down to up. The space under the stairs is nothing but a side-effect, but we don’t let that space lie dormant. The space creates an opportunity for storage and thus, the cupboard under the stairs. One wonders whether Harry Potter is a spandrel of a spandrel, in a sense.

Brains have heaps of useless space

Human brains are enormous and we don’t really understand why. We can explain some of this in terms of processing power. Just like a computer, the bigger the size, the better the processing power.

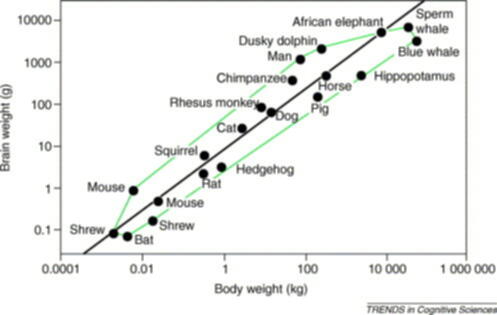

We can kind of measure this with the ‘encephalisation quotient’ (EQ). That is essentially how big your brain is vs how much body mass you have. The bigger the brain in relation to your mass, the smarter you probably are in comparison to other animals around that size. If you graph it, you can see that the more successful animals tend to have a higher EQ. But this only goes so far. Eventually, the EQ stops having any explanatory power. Especially when you look at humans. Look at the below graphs from this paperby Roth and Dicke.

The only EQ bigger than us are neanderthals and they went extinct because we either ate or screwed them all to death. If they're as smart as this graph hints that they are, it's probably the latter. Graph of brain size vs animal size.

The only EQ bigger than us are neanderthals and they went extinct because we either ate or screwed them all to death. If they're as smart as this graph hints that they are, it's probably the latter. Graph of brain size vs animal size.

In the first, the line represents what the average brain size for the body size is. We can see that the classically ‘smarter’ animals are way above the line. Though, it’s well known that as we move toward the larger end of the scale, it starts to be a less useful measure.

In the second graph, look at the brain volume measured against the body weight for some typical primates. See how enormous our brain is in comparison to our smartest brethren, the chimpanzees. And look how quickly the size ratcheted up. The green line represents human ancestry, and we might not be sure from which of those various species we descended from, but our brains sure grew fast from one iteration of humanoid to another. Surely processing power couldn’t explain this benefit entirely, or why wouldn’t all apes have EQ’s as big as us?

Well, it might very well be that the human brain is full of spandrels. Think about the computer. It was developed for some very specific purposes. Computing big numbers, storing data and so on. In fact, we buy a computer for very specific functions. Perhaps mostly for word processing, or consuming media. But the power of the computer lends itself to far more uses than it’s original design, and so we used that power to create computer games and all sorts of other things that never crossed the minds of the original inventors. If our brain is full of by-products that by happy accident we managed to make useful, then it would certainly explain why our brains got so big, so quickly.

Language is one of the most commonly cited examples of a possible brain spandrel. Almost all animals communicate to some degree. Communication is fantastically useful. But to knowledge, no animal really communicates like humans do.

So much of what we talk about is adaptively useless. It might very well be that the size of our brain allowed language to blossom from the communication of ordinary and important information into something far greater. Eventually, language in this new, expanded form became useful in and of itself. And so, our brains continued to grow to accommodate the useful properties of this thing that was originally a useless byproduct.

This trait may have then gone on to become writing. Again, plenty of animals leave communication marking on things (think of the dog marking it’s territory). But no other known animal writes down stories and memories.

It seems a little nihlistic, but our specialness might have been nothing more that a happy accident. The product of the cupboard under the stairs.

Ideologies worth choosing at btrmt.

search

Start typing to search content...

My search finds related ideas, not just keywords.